Before the coronavirus pandemic shuttered schools last year, David Rushing was an energetic 15-year-old who liked to play basketball and baseball. He was an avid swimmer and a member of the Jesse White Tumblers — performing high-energy stunts like backflips and somersaults, sometimes in front of large audiences.

Then COVID-19 swept across the country and forced Chicago schools to close, leaving David, who has been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder, unable to participate in sports and without the proper support to help him focus in online classes.

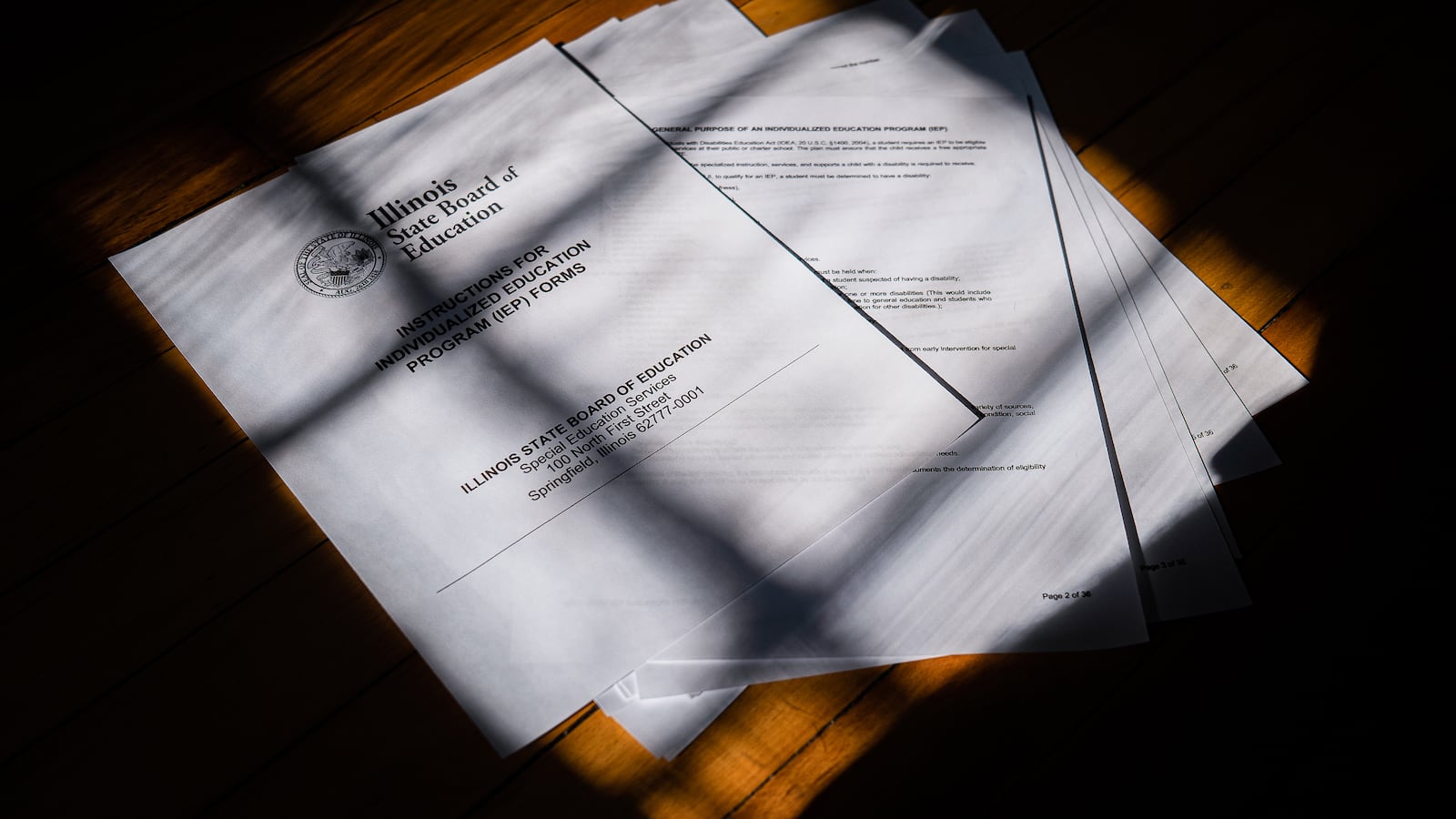

At the beginning of his freshman year at Dunbar Vocational Career Academy last fall, David’s Individualized Education Program, a legally binding document known as an IEP that outlines what special education services and interventions a student should receive, was set to expire on Nov. 5, 2020. He was to be re-evaluated for a new plan the month before. But that didn’t happen.

Within a matter of months, David’s life spiraled out of control.

Yvonne Bailey, David’s biological grandmother who adopted him at a young age, noticed David behaving differently.

David “got involved with the wrong people in the neighborhood,” Bailey said. “He was running away from home and staying out all night.”

David’s case is not isolated. The pandemic year has uprooted support for students with disabilities in Chicago and nationwide, creating a backlog of old IEPs that could lead to widening academic gaps for students in need of special education services. Students with disabilities make up 14.6% of Chicago’s enrollment, almost 50,000 students. Nearly half of those students are Latino, and about 40 percent are Black.

New data obtained by Chalkbeat shows that during the 2019-20 school year — which saw an 11-day teacher strike and COVID-19 school closures — more than 10,050 re-evaluations, initial evaluations, and annual reviews were incomplete, a more than threefold increase over the previous school year. More than 3,500 students, like David, were waiting for a re-evaluation that is required by federal law.

The data shows improvements during the 2020-21 school year, but 1,768 students were waiting to be re-evaluated and 230 were waiting for an initial evaluation to get an IEP.

Hidden from public view

Delays in IEP re-evaluations were a pre-pandemic problem that landed Chicago Public Schools under state review. In 2018, the state board of education appointed a monitor to ensure that Chicago was not denying or delaying special education services to students. In June of this year, the state board of education approved another year of state oversight.

Even though the coronavirus pandemic made it difficult to conduct IEPs in person, schools were still responsible for updating the plans and had to provide remote evaluations. Yet despite issuing waivers for such activities as standardized testing, the U.S. Department of Education never waived any part of federal law meant to protect students with disabilities.

Correspondence between Chicago, the state board of education, and special education advocates in the city shows that as far back as September, officials had evidence that the pandemic had disrupted students’ services.

In a September letter obtained by Chalkbeat through an open records request, the district’s Office of Diverse Learner Supports and Services acknowledged that some evaluations were left “indeterminate.” The district promised in the letter that all evaluations would be completed during the 2020-21 school year.

Some parents and advocates say that did not happen, and data released by the district show some students were still left waiting during the 2020-21 school year. But the full scope of the problem is not clear because Chicago Public Schools continues to withhold key data points that indicate compliance with federal special education law, including the race of children whose families seek evaluations and how many referrals were initially requested by parents or educators.

Chalkbeat sent Freedom of Information Act requests to both the state board of education and Chicago Public Schools in March asking for data on how many students were waiting for initial evaluations to create an IEP and how many students needed to be re-evaluated to update their current IEPs during the 2018-2021 school years.

The state board referred Chalkbeat back to Chicago Public Schools officials, saying that the state only has limited access to the district’s database that tracks the status of students’ IEPs. Chicago Public Schools extended the information request deadline several times. In April, Chalkbeat went to the state’s Attorney General Public Access Bureau for assistance, but the district still refused to provide the data. In late July, the district partially released data weeks after Chalkbeat filed a lawsuit against the school district in the Cook County Circuit Court. (Chalkbeat is represented by Loevy & Loevy, a civil rights firm.)

The data Chicago released in late July offers a first public look at end-of-year numbers for the 2018-19, 2019-20, 2020-21 school years and shows how many re-evaluations, initial evaluations, and annual reviews were completed and how many were left incomplete. Across the three categories, students in need of annual reviews were most likely to face delays, with about 8.7% of eligible students waiting in 2019-20 compared to 1.7% the year prior.

According to the data provided by the district, broken down by network, the 2019-20 school year saw the highest numbers of students waiting for a re-evaluation. The number of students waiting depended on where they attended school in the city and what type of school it was. Students who attended schools in Networks 11 and 13 — the former spans Englewood and parts of the Southwest Side and the latter cuts across neighborhoods on the city’s far south and far east sides — were unlikely to be re-evaluated during the school year.

Also, the district’s turnaround school operator, the Academy for Urban School Leadership, or AUSL, which was tasked with managing some of the lowest-performing schools in Chicago until the district decided to phase out the program earlier this year, had a higher rate of non-compliance during the 2019-20 year, with 40.9% of re-evaluations left incomplete. Charters as a whole tended to perform better than city averages during 2019-20, with 17.8% of re-evaluations incomplete compared with a citywide average of 25%. The following year, however, charters did not comply as well as most of the district-run networks, reporting some of the highest numbers of incomplete annual reviews and initial IEP evaluations and reporting middle-of-the-pack numbers for re-evaluations.

Chicago Public Schools denied a Chalkbeat request to interview a representative from the district’s special education department. However, district spokesman James Gherardi said there were complications re-evaluating students with disabilities due to the pandemic and a year of related school closures.

“The COVID-19 pandemic added a layer of difficulty to the evaluation process that our school leaders and staff are still working through to ensure each student that needs an evaluation receives one,” said Gherardi.

Families search for options

That still leaves family members such as Yvonne Bailey, David Rushing’s mother, desperate to find help for struggling students.

Bailey went to Equip for Equality, a nonprofit legal service organization, to get help with getting David’s evaluation. With Equip for Equality’s help, David was re-evaluated in the spring and a new IEP was written in April.

Unlike Bailey, many Chicago parents are not able to access legal services. Instead, some have decided to leave the school district to ensure that their child receives special education services.

For some families, the issue wasn’t the timeline. It was poor execution.

Courtney Aviles moved to Cincinnati after spending a year trying to get her 5-year-old son re-evaluated for an IEP. When her son was in preschool, a teacher raised concerns about his fine motor skills, especially his ability to write.

Before schools shut down in March 2020, Aviles’ son had an annual IEP meeting to assess current goals, at James B. McPherson Elementary School, on the city’s north side. Aviles, a former teacher in Florida, was taken aback to see that her son’s teachers and case manager, who previously worked with him, were not there to speak about his needs in the classroom. Legally, schools are required to have teachers and case managers present at IEP meetings.

“As a former teacher myself, I feel that it greatly impacted our ability to conduct the IEP meeting,” said Aviles. “Having his teachers there to share their experience with and to advocate for my son would have made the meeting more productive.”

During the annual meeting, Aviles and the IEP team agreed that her son would be evaluated for occupational therapy to help him write. However, schools across the state were shuttered in response to the coronavirus pandemic and Aviles’ son did not receive special education services for the remainder of the year.

At the beginning of the 2020-21 school year, Aviles transferred her son to Helen C. Peirce School of International Studies. Prior to the start of the school year, Aviles emailed the school’s case manager to inquire about the occupational therapy evaluation discussed at her son’s last IEP meeting in August.

Aviles did not hear back from the case manager until October.

The case manager emailed Aviles to say that her son’s previous school had not finalized the assessment plan needed to get him evaluated for occupational therapy. Aviles signed a consent form to be connected with the school’s occupational therapist for an evaluation.

However, Aviles’ son, who was supposed to be evaluated by Jan. 22, 2021, never received an assessment. In February, Aviles and her son’s IEP team again gathered to update his program. The team concluded that Aviles’ son would need a full re-evaluation — but that didn’t happen.

By March, the family moved to Ohio. Aviles called it a “spur of the moment” decision after visiting friends for her son’s birthday. Aviles and her husband felt that they could make a good life for their children in Cincinnati. She said that while she loved Chicago, struggling to get special education services for her son was a major factor in her decision to move to another state.

Aviles wished she would have pushed harder for her son’s services, but felt she had to maintain a good relationship with the school’s staff. “It could be a really delicate balance,” she said.

A national problem emerges

The stakes for students who do not receive a re-evaluation are high, according to Rachel Shapiro, an attorney at Equip for Equality.

“We explain it to parents that your child’s development could progress or there could be regression,” said Shapiro. “We have no way of knowing that without having some kind of standardized data.”

When the district delayed special education services for David Rushing and Aviles’ son, both boys saw a regression in their skills and changes in behavior. David started to run away from home and Aviles’ son struggled to learn how to write.

While working with parents, Shapiro claims that schools in Chicago were using the pandemic as a cover to only review IEPs and not perform evaluations.

“Part of the evaluation is that it has to be thorough and contain multiple different assessments because we don’t want to diagnose students based on one assessment,” she said.

A student’s IEP team — which includes teachers, case managers, and therapists — are supposed to meet every year to review a student’s progress, address any concerns, and update that student’s goals. The state requires re-evaluations every three years. Parents must be proactive in ensuring that their child gets what they need, said Shapiro.

Correspondence between Chicago, the state board of education, and special education advocates in the city shows that as far back as September, officials had evidence that the pandemic had disrupted students’ services.

Shapiro suggests parents document requests in writing and ask for standardized assessments, progress data, and requests for IEP meetings. If things don’t go well, Shapiro says, parents can request a mediator from the state board of education or file a complaint with the board.

According to Lindsay Kubatzky, policy manager at the National Center for Learning Disabilities, an advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C., school districts across the country have a backlog of evaluations due to the pandemic. Also, some school districts were concerned about the validity of doing evaluations remotely.

Kubatzky recommends that school districts communicate with parents about what to expect from the evaluation process this year.

“We see that the strongest indicator of whether a school district is doing a good job at evaluating or re-evaluating is whether parents have the information that they need and have a good understanding of what the process will look like,” said Kubatzky.

Kubatzky also urged school districts to use emergency federal funding to increase staff for evaluating students.

“So one thing that they could do is hire additional paraprofessionals to work with students to do some of the evaluations or contract with outside evaluators to help with the workload,” said Kubatzky. “There’s resources outside of the school building that could be beneficial for students and families.”

Chicago Public Schools said that it will spend $17 million to hire 78 nurses, 44 social workers, and 51 special education case managers for next school year.

What’s next for students

Since leaving Chicago, Aviles has turned to private occupational therapy for her son and has seen a lot of growth in his writing skills. In the fall, the 5-year-old will be attending kindergarten at a smaller school district in Cincinnati.

“At CPS, he couldn’t even hold a pencil. He can write his name, he’s writing letters and he’s recognizing letters,” said Aviles. “It’s a huge amount of growth in a super short period of time and it’s really unfortunate that it took a move to do that.”

Yvonne Bailey’s son, David, has been doing much better since he received an updated IEP. At the end of the school year, Bailey signed him up to attend in-person school two days a week. This summer, David was enrolled in the school’s football camp.

David will be returning to Dunbar for his sophomore year. Bailey feels that in-person learning will be better for him, especially when more students are at school.

“David does well around people. He likes hanging out with the kids like any kid at this age,” said Bailey. “So I think it’ll be better.”

Samantha Smylie began this project at Chicago Headline Club’s FOIAFest 2021 Boot Camp under the mentorship of journalist Angela Caputo, an investigative reporter at APM Reports.

Having trouble viewing our survey? Go here.