Chicago Public Schools has struggled from the outset to establish an effective school-based COVID testing program — a key component of the district’s strategy to keep campuses open safely and something it promised from the day schools opened last August.

After a fumbled rollout, just 16% of students had signed up for school-based testing as of Dec. 10, according to data Chalkbeat obtained in a records request. The district has not answered questions about whether it would be disclosing more up-to-date testing data.

Now, under a new deal with the teachers union after an impasse delayed the return to school after winter break, the district has an ambitious goal: getting consent to test 100% of students in the next two weeks.

That goal is a critical part of an effort to keep a fragile peace with the union following a standoff that saw the nation’s third largest school district cancel five days of classes after teachers voted to go remote over the district’s COVID mitigation strategies.

Testing capacity and opt-in rates among students were a point of concern in the negotiations and, in the coming weeks, will be a focus as the district seeks to fix the flaws in the testing program, boost sign-ups among reluctant parents, and deliver more tests throughout the district.

The agreement reached by the union and district does not lay out a clear pathway to do that.

But there have already been steps taken to boost testing participation.

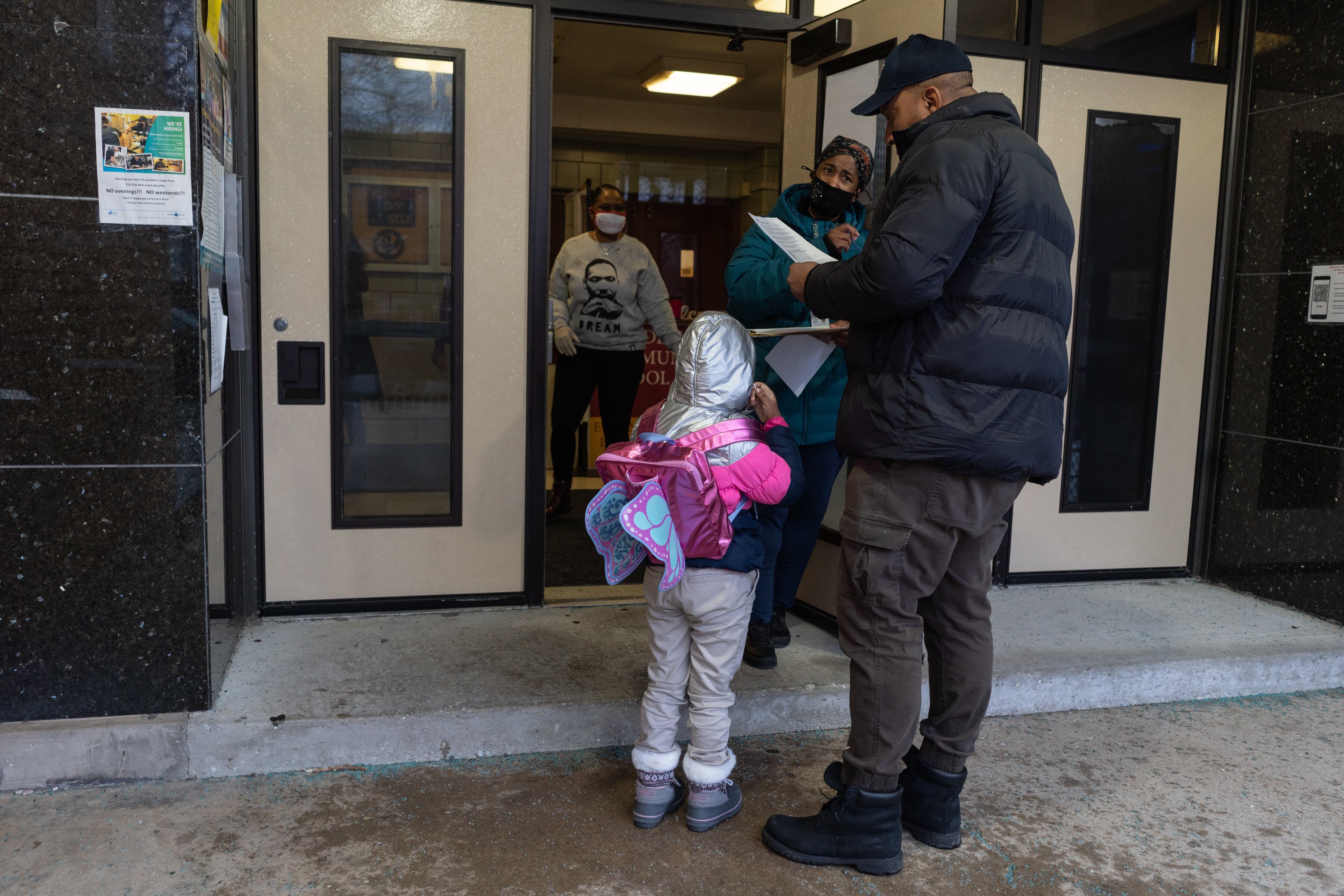

At some district schools this week, teachers have been allowed to get verbal consent from parents for testing — an alternative to a series of online forms that some parents said were cumbersome to complete.

The district also confirmed it had received 350,000 rapid test kids from the state and would use them for the remainder of the year. On Thursday, the district emailed parents to promote its testing program, stating that it plans to offer testing to 10% of students at each school and provide additional testing at schools with higher rates of COVID cases.

“The agreement we have reached with the Chicago Teachers’ Union honors our shared commitment to our students, families, communities, and each other,” the district told families in the Thursday letter. “We return to the classroom as one family, standing shoulder-to-shoulder in service of our young people.”

But the district didn’t respond to questions regarding possible changes that would make it simpler to get testing consent from families, how it planned to get 100% student participation in testing without it being a requirement, or how it planned to use the additional 350,000 tests obtained through the governor’s office.

Flaws in the testing system

Before a return to in-person learning, Chicago Public Schools set out to make testing a centerpiece of the district’s COVID safety strategy. In August, Interim school chief Jose Torres told WTTW the district would be testing all students and staff weekly, noting at the time that “This goes way beyond the CDC recommendation.”

But the promise of weekly testing for all students and staff never materialized. Chicago Public Schools completed 127 tests at schools during the first week of school between Aug. 29 and Sept. 4. At the start of the school year, the district also failed to meet its deadline to implement a testing program at every school. They cited staffing shortages with its vendor.

The district has ramped up testing over the last few months, conducting more than 33,300 tests the week before winter break between Dec. 12-18, data shows. Currently, it has the capacity to test about 40,000 students and staff per week.

Months into the school year, local school councils and union leaders raised concerns of insufficient testing supplies and infrequent testing at schools across the district. At some schools, testers wouldn’t show up. But most troubling, schools in neighborhoods hardest hit by COVID were not signing up for surveillance testing, data shows.

As of Dec. 10, about 16% of the district’s 330,000 students — up from 7% in October — had opted into testing across the district, and the rates of testing vary widely by schools. South and West Sides schools with predominantly Black and Latino student populations have among the lowest opt-in rates.

More than 200 schools still had fewer than 10% consented for COVID testing as of Dec. 10, according to the testing data Chalkbeat obtained. About 70 schools have fewer than 10 students enrolled.

That’s compared to 36% in New York City, 74% in Detroit, and 32% in Newark — though an analysis by the Center for Reinventing Public Education shows requiring all students and staff to be tested is rare.

In Los Angeles, the nation’s second largest school district, all students and staff members are mandated to test weekly to go to school. The district also required all students and staff to have a negative COVID-test before returning to campuses Tuesday due to the omicron surge.

In Washington, D.C., students and staff were required to present a negative COVID test before returning from winter break.

Amid the latest COVID surge, Detroit is mandating testing for students for in-person, or they’ll be transferred to remote learning beginning Jan. 31. New York officials are considering moving from an opt-in model to an opt-out model, but have yet to make a decision.

Looking ahead

Under the district’s latest plan with the union, weekly testing will be offered to at least 10% of students randomly selected from the consented student population at each school, and school nurses, school assistants, and other staff will be recruited to help increase testing capacity.

The district aims to reach 100% consent by Feb. 1. through phone banking at schools. Staff will be paid a non-instructional rate of pay for time spent phone banking outside of their regular work day, according to the agreement between CPS and the union.

At Woodlawn Community School on the city’s South Side, more than 89% of students have opted into the testing program — the highest rate across district schools. The school took a hands-on approach by calling, emailing, and meeting parents to get them signed up for testing since children returned to the classroom in the fall.

It’s not clear how the district will deliver on getting all students consented. But on Tuesday, teachers were already working their class registers, they said, calling parents to get verbal consent.

Hilario Dominguez, who teaches students with disabilities at Cooper Dual Language Academy, said he spent his first day back at the Lower West Side school calling parents to increase the overall opt-in rates at the school, which currently sits at about 1.56%.

He discovered his school’s low testing opt-in rates from a Chalkbeat report last week.

“I called parents all day getting students signed up for testing if parents wanted and resources for vaccination,” Dominguez said Tuesday. “Many of my families that I called shared their fear of going in with everything happening.”

Language barriers, lack of promotion, and a cumbersome opt-in process could be contributing to the low number, according to some parents who spoke with Chalkbeat.

In October, parent Sarah Spraker, whose son and daughter attend Ole A. Thorp Elementary Scholastic Academy, told Chalkbeat she nearly missed opting her children in because the email notification came from a laboratory and not the school.

“I don’t feel like CPS has blasted parents enough to sign up for this,” Spraker said. “It takes a lot to get parents’ attention. I think more parents would opt in if there was more communication.”

During dropoff Wednesday morning at Cooper Dual Language Academy in Pilsen, parent Jenny Reyes said she hadn’t even heard about the school-based testing program until she received a phone call from her daughter’s teacher a day earlier.

“I had never received information or I missed the email,” Reyes said.

Parent Marisol de Paz gave consent for her two sons at the Pilsen school after getting notification from a community group a day earlier.

“I think it’s easier for them to do it here weekly,” de Paz said. “At the same time, if I notice any symptoms I get them tested. I’m the most interested in making sure my kids and family are healthy.”

Some parents remain wary about the testing program run by the district. Reyna Garcia reached out to the district to get clarity on the testing program, but received conflicting information.

In those conversations, she decided not to consent to testing. If her son is sick, Garcia said, she just won’t send him to school.

“I don’t see the point of some getting tested and some not,” Garcia said. “What’s the point of him getting picked every week when other kids aren’t going to do it? It doesn’t make sense.”