This school year, my eighth grade students took part in two very different conversations mere days apart – one focused on how the Kyle Rittenhouse verdict reinforced so much of what is broken in our country, and the other focused on justice finally being served against Ahmaud Arbery’s killers.

My students wanted to talk more about the hatred that fuels violence and the role of cell phone video in decisions to acquit or convict. I did my best to facilitate meaningful dialogue in both cases, knowing the immense weight on young people in these moments and the equally great responsibility I hold as their educator.

As a Black woman teaching in Chicago Public Schools for more than 25 years, I’ve spent plenty of time considering how my race impacts my work. But no matter their race, gender, or identity, all educators need to be able to stand in front of our classrooms, gain the trust of our students, and empathize with them.

My years in front of the classroom have taught me that students don’t need our sympathy, but they do need our empathy and action. Although the stakes are higher than ever, educators aren’t being given what we need to navigate the most difficult conversations of our day. Sure, we’ll get the occasional lesson plan, but what we need is in-depth, ongoing, and mandatory training and curriculum about identity, race, and racism. Resources must be devoted to making that a reality.

Instead, it’s been up to teachers to foster a classroom that is responsive to our students’ experiences. Instead of avoiding uncomfortable conversations about history, I work every day to make my classroom a space where students can have open, honest dialogue on topics ranging from police brutality to the recent verdicts. I want them to know that my classroom is a safe place, physically and emotionally, and somewhere their voices are valued. It’s a place where current events can be discussed with nuance, even when it’s uncomfortable.

I try to honor my students’ lived experiences. If a child talks back, for example, I work to understand the root causes of their behavior. If a student is disengaged, I am sure to ask them about what’s going on in their lives and do my best to provide the support they need.

But I need more help than I’m getting. The district and our union need to step up to make widespread training available now. How can we expect educators to help students navigate racial complexities if they are not given the tools to unpack and understand what’s at issue?

There is repeated trauma, especially for our students of color, when we have to address these kinds of events repeatedly. If we facilitate these conversations well, we stand to build a level of trust and empathy with our students that will transform our ability to teach them. If we don’t, we stand to lead classrooms that don’t feel safe for all of our students. Good intentions aside, we could exacerbate their trauma.

Although the stakes are higher than ever, educators aren’t being given what we need to navigate the most difficult conversations of our day.

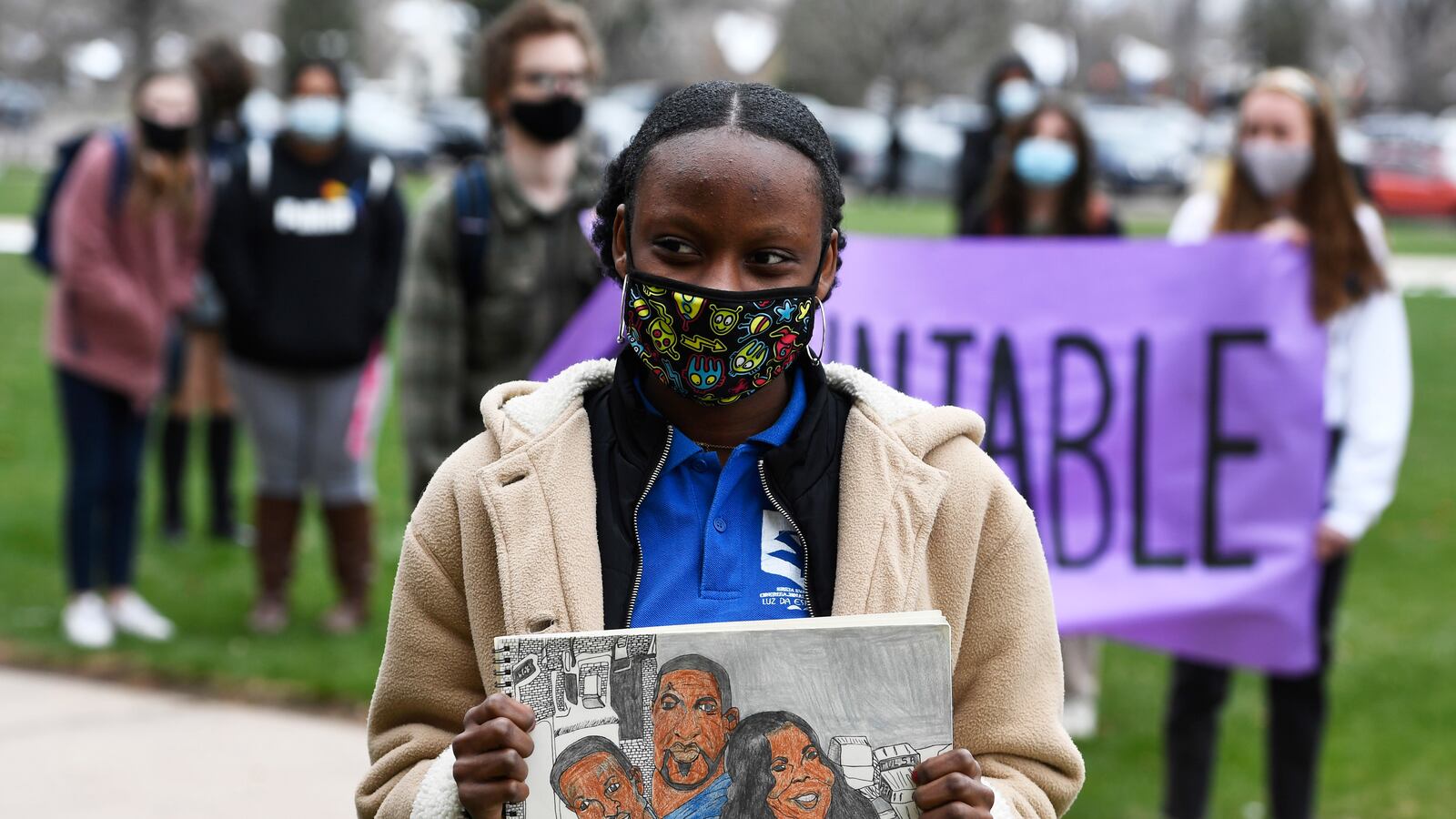

It’s been said time and again that the pandemic and the racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd have laid bare what so many of us teaching in classrooms have known for decades: Our school system is built atop an inequitable, racist foundation. In Chicago Public Schools, we teach students with incredibly diverse backgrounds, all of whom are impacted by longstanding and intersecting systems that reinforce racism and poverty. Dismantling those systems will take time and effort.

Knowing this, I’ve long been an advocate for widespread and ongoing educator training around topics such as identity, implicit bias, trauma, and antiracism. In the past year and a half, there’s been a lot of talk about the importance of these practices in our schools. While I’m glad our district and our union can agree on their importance, I’m imploring them to move past agreement and into action so that educators will no longer scramble to address the critical events and conversations that are shaping our students’ lives.

Dr. Winnie Williams-Hall is a diverse learning middle school teacher at Nicholson STEM Elementary. Dr. Winnie has been working in Chicago Public Schools for over 25 years.