For Jennifer Dixon, the principal of John M. Palmer Elementary School in Chicago, steering the ship during the pandemic has involved creative adaptations of old traditions — and the introduction of new ones.

Enter the dance parties and the chickens.

The dance parties were a Palmer tradition long before the pandemic. Music pipes over the intercom every Friday morning, and the school’s 700 children and the staff jam out in the hallways. When school closures abruptly sent children remote, Dixon’s team moved the weekly party online and had families send in videos of children dancing.

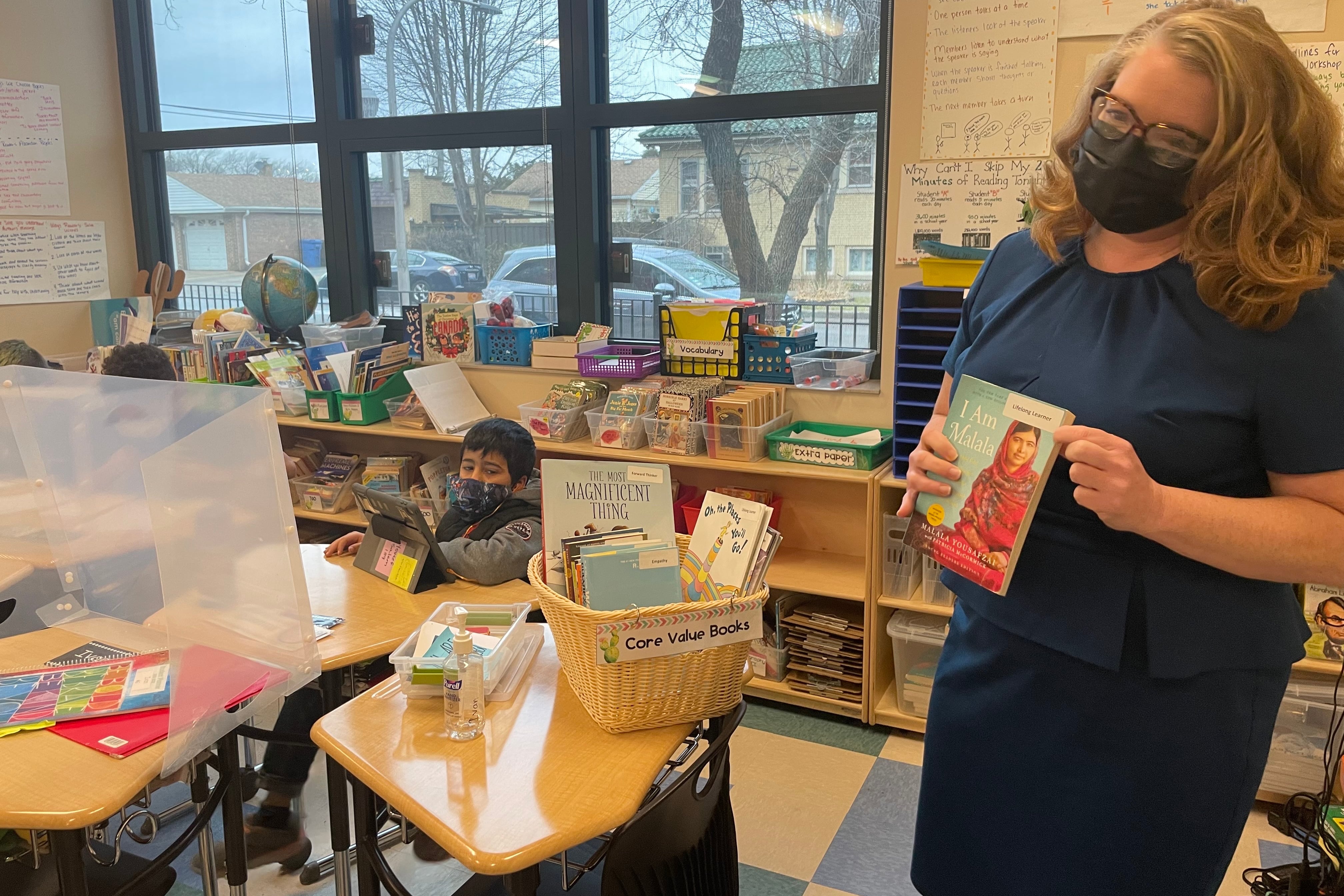

The COVID era inspired new traditions, too. Outside the building, a clutch of hens now graze in a fenced-off grassy area — and their coop has become an attraction that has engaged students, parents, and neighbors alike. Inside the buildings, teachers have introduced a kindness curriculum — a project that earned Palmer a Kind School Award from Stand for Children Illinois.

Such traditions have rooted the school during rocky times, from COVID closures to hybrid learning to a recent five-day district-wide shutdown during a contract standoff between Chicago Public Schools administrators and the city’s teachers union. “No matter how many times we have to be flexible,” said Dixon, a reading specialist and Harvard-trained educator who has led the school for a decade, “we’re doing the best we can and we’re focusing on meeting the needs of our students.”

The Chicago principal sat down with Chalkbeat to talk about steeling her school community in an era of unpredictability, reaching kindness, and finding hope.

Your school already used several social-emotional programs when you decided to introduce a curriculum centered on kindness. Why?

It was driven by teacher interest. I see my role as a school leader to make sure everything is aligned and that we’re all moving together in the same direction. But there’s opportunities for teachers to serve in a leadership capacity, and for them to take the lead on projects that they find valuable across the school. So I got an email from Stand for Children (about the Teach Kindness curriculum), and I forwarded it to my entire staff. And I said, ‘Write back to let me know if you’re interested.’ And a bunch of people said yes, and then it took off.

There’s always some wiggle room for new ideas and things. And I think that when you’re talking about school improvement, it’s just super important to have a plan, but also be flexible. Because situations change.

It has been a very difficult few years for everyone. What are you doing differently to account for what so many families have been through with COVID?

I tried to make sure that, no matter what information was coming to me, I was keeping our school community safe, and that I was as transparent as possible. While we reviewed new guidance, [the assistant principal and I] created a shared document for teachers to ask questions. We had optional meetings for teachers to look at the plan while it was in development to give us feedback along the way. With teachers, I listened to them share their worries and their concerns. And then I also thought about how to engage the families and the students to make sure that they weren’t scared.

There were a lot of meetings and a lot of conversations, but we’ve done some creative things to bring together our community. When we were fully remote, we had these social-emotional learning days, where all day was just about exploring interests and feelings. We made a menu of Google Meets links [to remote classrooms] on those days, and it was a good self-select-your-path for the day. There was yoga, art, and music, and I taught a class all about pugs. The kids really liked the dogs!

What did running a school during the early part of the pandemic teach you?

Early on, we realized the level of food insecurity. We have a “Friends of Palmer” group, and they started a food drive and food pantry. So when we were passing out free lunches (through the CPS free lunch program for students), parents volunteered to give away pantry food. I remember passing out food and learning about food insecurity and how it is more [common] than I thought.

We started a chicken coop during the pandemic. We were thinking: What are some ways that we can bring kids to the school, but safely? And in little groups? We now have families who volunteer to care for chickens and a chicken coop committee that organizes their care.

This year has been a lot. But I think we were already set up to not crumble.

Has there been anything in your career up to this point that prepared you for this school year? If so, please elaborate.

I’m not quite sure if anything could have really prepared me for the past three years. I got my leadership degree through the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 2012, and I was graduating that spring. We had found out my mom had cancer that May. And she died July 3, 2012. So the last thing she went to was my graduation. She was actually really sick but she just let on like she wasn’t. I don’t think there is a harder life lesson.

I recognize in my leadership that we’re in a vulnerable moment. We cannot neglect our humanity. Everyone — every single person — has a story. All the teachers that come here to the school, and all the parents, and the people who live in this wider community — they all have a story.

How are you guiding your staff through this school year?

Imperfectly. I’ve said we’re going to manage the things that we can, and there are some things we can’t do anything about. We’re going to give ourselves grace, and we’re going to give ourselves forgiveness. And we are going to try to make this day that we have the best day that we can.

We have talked a lot about restorative conversations with kids. Sometimes we have restorative conversations with adults.

What is the best advice you have ever received?

That complex work happens in simple structures. I say that all the time. Sometimes when you have too many sheets and forms, or if things look too fancy, they don’t stick. But it will if you create a simple structure, such as a schedule that allows teachers time to collaborate or a student referral form to a behavioral health team.

Your school has been designated as an exemplary supportive school, including the use of a behavioral health team. How does it work?

The CPS office of social emotional learning really provided a vision for what the ideal situation would look like. And really, we just did it. We have a referral form for teachers that includes The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (a widely used mental health screener for children and adolescents), and when teachers need support, they [send] the form and a set of data filters back to our counselor, our social workers, and myself and the assistant principal.

The team meets biweekly and they go through the referrals, and we have a whole host of programs that we have access to — from Rainbows (a program for children experiencing grief) to small groups to work on social skills. We also partner with Lutheran Social Services of Illinois to have an additional counselor in-house who meets with a caseload of about 25 students individually.

What gives you hope at this moment?

That this pandemic isn’t forever.