Chicago Public Schools reopened its doors Monday amid the city’s steepest COVID-19 surge but the question of whether the district can keep school buildings open loomed large.

The Chicago Teachers Union is set to vote Tuesday on whether its members would refuse to report to campuses in-person until certain safety conditions are met, sparking yet another period of uncertainty for parents and students.

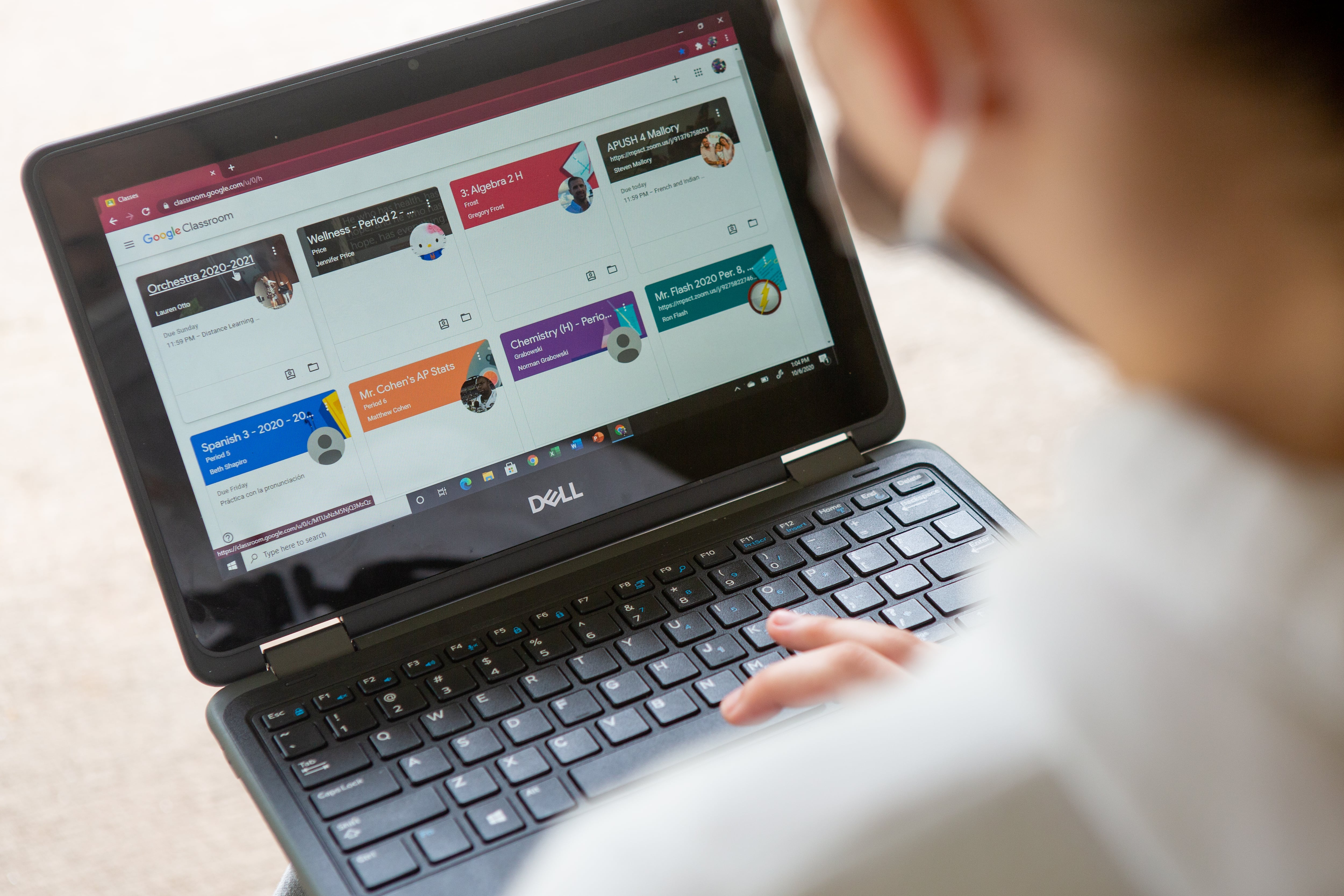

If teachers vote to refuse to report to work in-person and instead teach remotely as they did one year ago last January, it could force schools to scramble to equip the district’s 330,000 students with devices and sufficient Internet service as soon as Wednesday.

The Illinois state board of education has yet to weigh in on the matter. This school year started with slim options for districts to go remote, but the state has clarified that local school boards can adopt an e-learning plan or extend the school year for missed days.

A Chicago Public Schools spokesperson said in a statement Monday afternoon that the district had met with Chicago Teachers Union leadership in the past week and would “continue to keep the lines of communication open.”

“We have reiterated that a case-by-case, school-by-school approach is the best way to address COVID-19 concerns in schools,” the statement said.

In Chicago, parents said they felt in flux and worried, some because of the rising positivity rate and others because of the potential for remote learning, which could again upend their lives and their children’s learning.

Nolberto Casas arrived at his daughter’s pre-K center Monday morning to find the doors locked and several other parents and children standing there bewildered. He said he did not see a notice from the pre-K center, which is run by a large Chicago nonprofit that receives public funding. (The center, which is run by Chicago Commons, posted on social media that it closed due to rising COVID cases, limited testing availability, and delayed results and hoped to resume services Tuesday.)

“I feel abandoned,” said Casas, who has an older child in first grade at Ruiz Elementary in the Pilsen neighborhood. Casas, who has helped organize parents to advocate for in-person learning, said he’s worried that his son will fall further behind academically if schools go virtual again.

He’s also concerned his wife will have to quit her job as a security guard to stay home with the children should virtual learning extend more than a few days. “Our children are 4 and 6,” he said. “A parent has to be home full-time.”

Cortney Ritsema, meanwhile, kept her three children home Monday. “They were supposed to return in person learning today but I kept them because, frankly, I don’t feel safe with the mitigations in place,” said Ritsema, who earlier in the year helped organize a “sick out” in hopes of pressuring the district to extend remote options for students.

In an email to parents Sunday night, Chicago Public Schools CEO Pedro Martinez acknowledged the anxiety of the moment but tried to reassure families that the district was committed to in-person learning and was doubling down on safety precautions, from universal masking to in-school testing to social distancing “when possible.”

“Research has shown that with the extraordinary protections we’ve put in place, school is one of the safest places your children can be during the pandemic,” Martinez wrote.

Asked Monday how leaders planned to respond to the union vote and the potential outcome of widespread remote learning, the district expressed concerns about the “health and safety” of the school communities should students be sent home. Mass school closures, the statement said, could fuel community spread.

Safety precautions a point of concern

The omicron variant, surging positivity rates, and breakthrough COVID infections have forced school districts across the country to make tough choices to start 2022. New York City’s schools — the nation’s largest school district — opened Monday with increased testing, while other districts, from Newark, New Jersey to Ann Arbor, Michigan, opted to start remotely.

While some smaller, suburban Illinois school districts, such as Niles Township High School District 219, shifted abruptly to a remote January start, nine out of Illinois’ 10 largest school districts reopened classrooms for in-person learning on Monday. Only Algonquin-based Community Unit School District 300 said it was canceling class for the day to see how the omicron variant has impacted staffing.

In Peoria, superintendent Sharon Desmoulin-Kherat and the district’s board of education decided to extend winter break until next week after a local surge in coronavirus cases. The district, which said it will extend the school year to make up for missed days, is offering to-go meals for lunch this week and sporting events for high school students will continue.

In Chicago, teachers union officials argued that the city needed to require negative tests of all students to return — or pause in-person learning for two weeks until more safety measures are in place and officials can agree on a metric for when to suspend in-person learning.

In making its case, the union has consistently pointed out flaws in the in-school testing program Chicago rolled out belatedly last fall, delays in contact tracing reported at several campuses before winter break, and persistent staffing shortages that have forced schools to combine classes or draft special education assistants and security guards into supervisory roles.

But a climbing city positivity rate and a botched winter break testing scenario have prompted the union to step up its action. Union officials said Monday that the district’s execution of a winter testing program was “incompetent.”

According to district data, after schools sent home 150,000 tests to students in high COVID transmission neighborhoods before winter break, only 35,779 completed tests were logged between Dec. 26 and Jan. 1. Of those, 1,963, or 18%, were positive — in line with the city’s positivity rate last week — and a staggering 24,986, or nearly 70%, were labeled “inconclusive.”

“I am so pissed off that we have to continuously fight for the basic necessities, the basic mitigations,” said Stacy Davis Gates, the teachers union vice president, on Monday outside of Park Manor Elementary School on the city’s South Side.

Keyonna Payton, a teacher who chairs Park Manor’s safety committee, said she worked alongside colleagues during the winter break to ensure students, most of whom were in quarantine when the kits were handed out, had access to testing before the return to school. She was disheartened to see those invalid test results.

Payton urged district officials to listen to the school’s safety committees to hear what they needed amid the latest surge.

“We are asking for safety,” Payton said. “We are fighting for the safety of our students.”

Parent Danelda Archer said she complied with the district’s testing precautions and got her two children tested but the results were ultimately inconclusive.

“How can I allow my children to come back and they don’t even have a negative or positive result?” Archer said. “That was supposed to be the end result to ensure they were safe going back into the building.”

Amid ongoing safety concerns, some Park Manor teachers planned on teaching remotely starting Monday. They said Monday they had received a letter from the school board threatening a loss of pay. When asked about the letter, the district did not respond.

Other Park Manor parents said Monday they would not bring their children to schools amid the latest surge, saying that the district’s testing and mitigation strategies were not sufficient to protect their children. The school had 10 staff members, including the principal, test positive in the days leading up to winter break, teachers and union representatives said.

Staffing shortages add to the pressure

Tuesday’s planned union vote also left some educators feeling conflicted.

One teacher at a high school on Chicago’s West Side said she wasn’t sure whether she would vote to teach from home. The educator, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, is a parent of two elementary-aged children, and she said supervising their remote learning while teaching high schoolers is a “nightmare.”

Plus, she added, “kids need to be in school” for academic and social reasons. A year of remote learning had shown her that.

Still, she said multiple absences of staff at her school Monday signal a rocky week ahead, whether or not teachers ultimately choose en masse to report to campuses.

In an attempt to head off staffing shortages that forced some campuses to combine classes before winter break, Chicago Public Schools also said it was offering a new $1,000 incentive for substitutes who work more than 15 days a month in January. The district last fall began offering substitutes a $420 incentive for months in which they work more than 12 days.

Chicago’s schools chief has also said he’d like to limit the number of students and staff in quarantine. In early December, Chicago Public Schools introduced a small test-to-stay pilot, which offered more regimented testing at one school. As of winter break, the pilot was confined to one school.

The latest guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reduces the recommended isolation period for anyone testing positive for COVID to five days if they are asymptomatic or if symptoms are resolving, followed by five days of strict mask use. However, the Illinois Department of Public Health has said that schools should continue to use a 10-day quarantine metric for student or staff members who test positive for COVID-19.

Samantha Smylie contributed reporting.