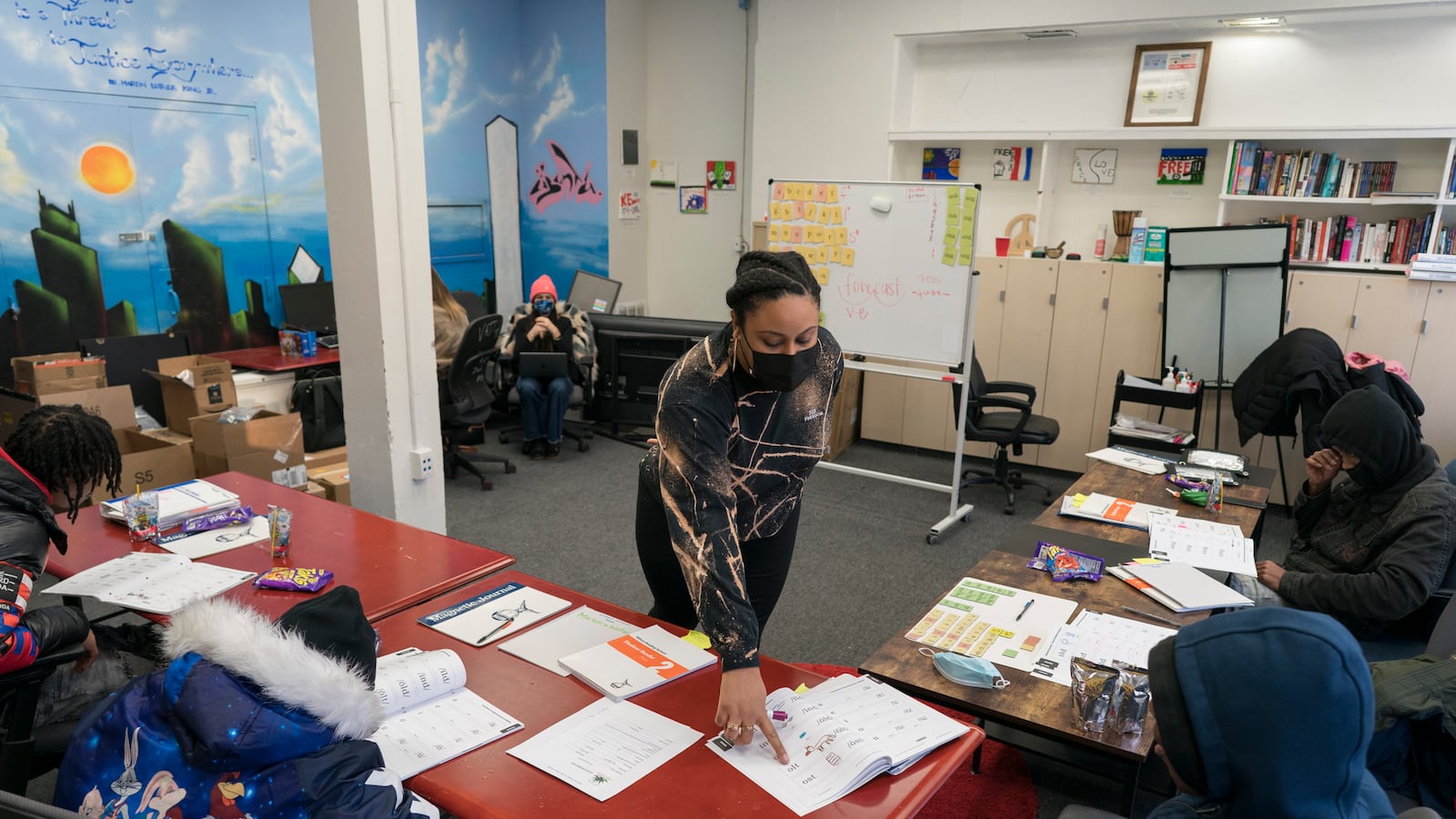

It’s the second straight day of torrential rains in Chicago, and the gym of the Lawndale Christian Legal Center is leaking. Moses, one of eight students in a literacy program for teens, pays it no mind.

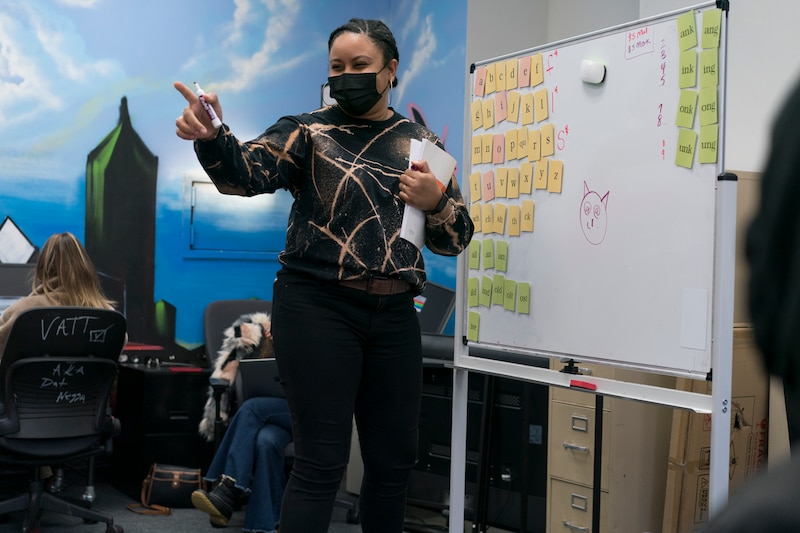

He’s focused on his teacher, Ronica Hicks, who is reviewing prefixes and suffixes.

“Let’s use a basketball analogy,” says Hicks, equal parts playful and stern. “A pre-fix is like the pre-game.”

The lights flicker. The water drips. But, even on this dreary October evening, Hicks — who, like her students, is Black — is undeterred. In one of the most troubled neighborhoods in Chicago, she’s on a mission to help this group of 16-, 17-, and 18-year-olds read beyond a first or second grade level.

The pilot literacy program, which is run by a tutoring and training organization called Redwood Literacy, has become a potential lifeline to the teens who’ve been flagged by case managers, probation officers, and judges for slipping through the cracks of public education. Somehow they each made it to high school without fundamental reading skills — skills strongly correlated with future employment, earning potential, even better health.

In Illinois, where curriculum is largely a matter of local control, there’s no centralized tracking of how districts teach children to read or recommended curriculum list. But there’s growing recognition, at least among some teachers, parents, and advocates, that some schools across the state — and even some campuses in large districts like Chicago — are clinging to debunked methods.

Hundreds of miles from where the teens sit in Lawndale, momentum is building for sweeping changes that could bring Illinois more in line with the 38 states that have begun widespread campaigns to tackle stubbornly low reading proficiency rates. A new Right to Read bill is being weighed by the state’s General Assembly, and could bring changes advocates say are long overdue.

At least one national research report has shown that students who don’t read proficiently at the end of the third grade are four times more likely to drop out of school or fail to graduate. Even before COVID upended in-person learning, only one out of three Illinois third graders met grade level standards for reading on a state test. Black students tended to fare worse — only one in five reading on grade level. For Latino students, it was one in four.

Sitting in the back of the literacy class one night, Kait Feriante, the founder and CEO of Redwood, wonders aloud how things got to this point for her students.

“How might their journeys have been different if they had been given the instruction they needed in second and third grade,” she asks, “and not just the last years of high school?”

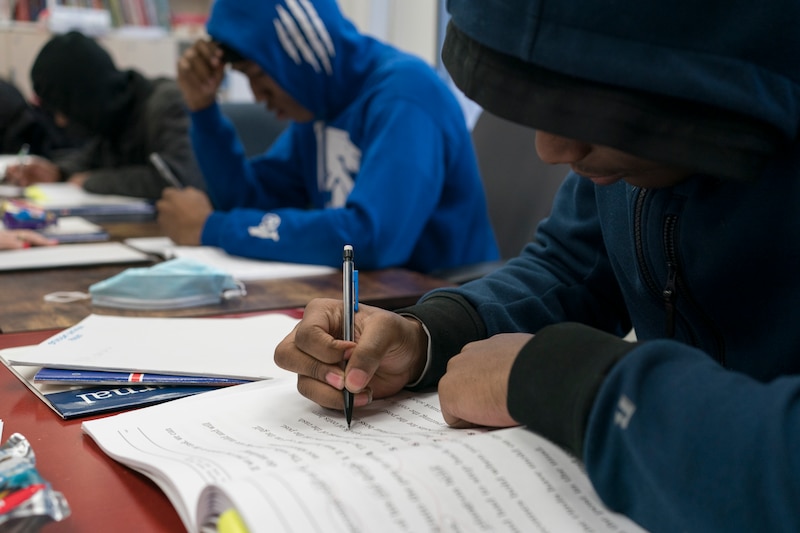

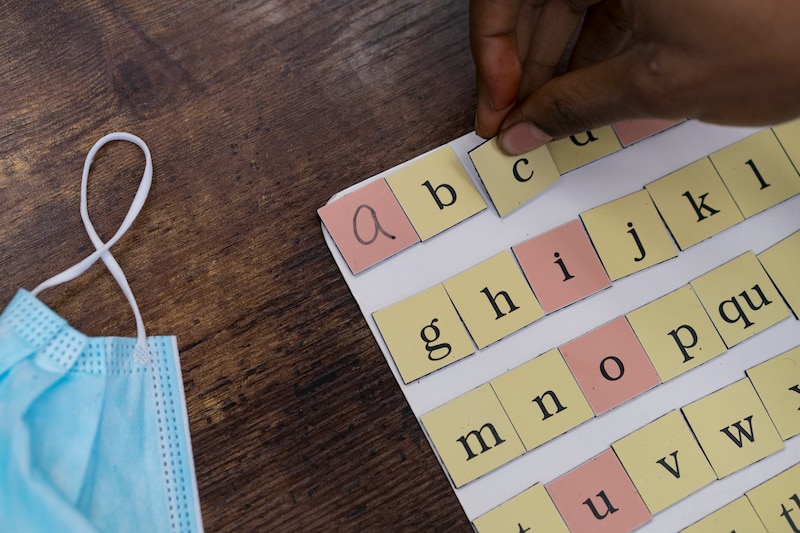

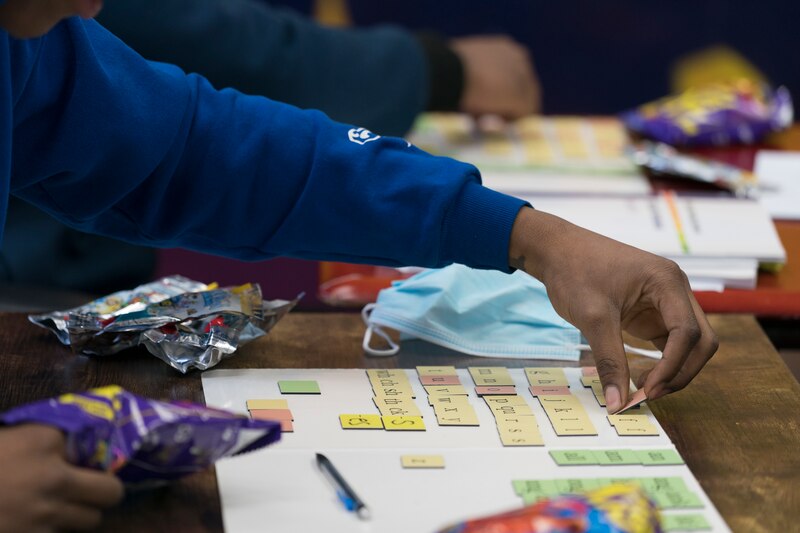

Hicks, a literacy intervention specialist, follows a strict protocol laid out by a curriculum called Wilson Reading System. Twice weekly, the teens meet in the Lawndale center gym for 90 minutes to practice sounds and high-frequency words, read aloud sentences, and write and manipulate letters on a magnetic letter board.

Mills. Shams. Lashes.

They smile when they get something right, race against each other to read sentences before an alarm buzzes, and engage in some good-natured teasing when asked to draw stick figures to check comprehension after silent reading.

The group also struggle mightily against distractions — emergency phone calls and text messages from friends and family in crisis; nights with too little sleep; and troubles waiting just outside the gym door. Because some participants have had recent involvement in the criminal justice system as juveniles, been homeless, or experienced the death of a parent, Chalkbeat agreed to use pseudonyms for this story.

Hicks has a mantra: In her classroom, there is no shame, only grace. If her students make it to the program’s graduation ceremony in the spring, they will have reached a lofty goal. For attendance of 80% or better, they’ll each earn $1,000.

Moses shows up every week.

“I always wanted to get a (special education plan) because I knew — I knew I couldn’t read as good as other people. I couldn’t spell as good as other people. I never got it. I never got that help,” he said, until a younger sibling’s case manager flagged him to be screened for Redwood’s literacy intervention pilot.

“This is something I really needed, and people have seen that I needed it. It used to hurt my feelings,” that he didn’t get more help, he said. “I was mad.”

Some schools are not following the science

Small but promising, the Lawndale program is an experiment now in its second year.

Even when Chicago high schools were mostly closed to students during 2020-21 due to the pandemic, the Redwood classes met in person and instructors worked mightily to counteract years that students described as full of failure and a feeling of invisibility. For nine students in the first group, attendance was 93% across more than 60 meetings, and the teens averaged 1.91 grade levels of growth on a benchmark assessment.

Particularly frustrating for Feriante is that there’s now a large body of research — known as the science of reading — that describes how the brain learns reading in detail. A key tenet is that explicit, systematic phonics is a must. In other words, teachers must directly and methodically teach children the connection between letter combinations and sounds.

“Structured literacy instruction helps all students and it is life-changing for some — we know what we need to do,” Feriante said. “This isn’t magic, it’s science.”

In Chicago and many other large Illinois districts, some schools still go against best practices by using an approach called “balanced literacy,” though exactly how many is hard to say since, like the state, Chicago Public Schools doesn’t centrally track reading curricula, either. “Balanced literacy” is an approach that mixes some phonics into whole-language instruction, a now-debunked philosophy based on the idea that reading is a natural process and doesn’t require direct instruction on decoding words.

All but about a dozen states now have passed laws focusing on early literacy instruction, and 18 states have used federal COVID relief monies to expand programs. These efforts run the gamut – from statewide curriculum recommendation lists of vetted materials, to widespread teacher retraining efforts, to third grade literacy screenings outside of required assessments, to a wholesale rethinking of how colleges and universities teach future educators.

In Illinois, where curriculum traditionally is the domain of individual districts, the conversation is just getting started.

In Plano, just west of Aurora, for example, a small group of teachers at a local elementary school began researching structured literacy during the pandemic and recently lobbied their principal to adopt a new approach. One of them, Pam Reilly, is a former Illinois Teacher of the Year and reading coach who said it has been a sea change at her school.

“I’ve been teaching for 25 years and to think back on all of the classes that I had been with. Did I do something wrong?” Reilly asks. “But I think when we know better we do better. We’re learning, and I think we have to move forward from here.”

Until it debuted a new curriculum called Skyline last summer, the state’s largest school district, Chicago Public Schools, left reading curricula mostly to the provenance of schools and even individual teachers, though the district described its overall approach in a statement as “grounded in the science of reading and the critical combination of decoding skill and language comprehension.” (CPS declined to make its literacy director available for an interview.)

School-level curriculum selection is still largely the case in Chicago, since Skyline is optional, and according to a Chalkbeat public records request, only 33 high schools, one middle school, and 121 elementary schools — about 30% of district-run schools — have adopted the English Language Arts portion, which has elements of structured literacy instruction for children.

Potentially compounding the problem: Nearly half the state’s teacher preparation programs receive failing marks in how adequately they prepare educators in scientifically based reading instruction methods.

A 2020 report from the National Council on Teacher Quality awarded a D or F to 43% of Illinois’ higher education programs that prepare future teachers — a higher percentage than nationally. The council gave 38% of the teaching programs an A or B, 18% a C, and it did not receive enough information to rate 10. (Some higher education leaders have criticized the report, calling it an unreliable gauge.)

“A lot of teacher programs and (teacher training) residencies are guilty about not paying attention to the science,” said Kate Walsh, the president of the council. “We are captive of higher ed in many respects.”

Causing further delays, COVID-19 and the pandemic’s ripple effects through school districts have effectively pushed out the conversation.

“Generally speaking, the early literacy issue is not a prominent conversation among superintendents,” said Kaine Osburn, the superintendent of Avoca School District 37. “Right now, with COVID, only COVID is prominent.”

About three years ago, school board members, teachers, and administrators in Osburn’s district began taking a hard look at how children there learn to read. Ultimately, the district adopted two sets of curriculum materials, launched teacher training for every educator, and began literacy screenings for every student in kindergarten through third grade.

Avoca school board members became so persuaded by the effort that they sponsored a resolution late last year putting the issue on the advocacy slate of the Illinois Association of School Boards. The resolution calls for the Illinois State Board of Education to require pre-service teachers in early learning to complete a course in their teacher prep programs solely dedicated to scientifically proven methods of reading instruction.

Those efforts dovetail with others bubbling up. A fledgling statewide Early Literacy Coalition has helped draft the Right to Read bill sponsored this session by Kimberly Lightford, a state senator long frustrated that Illinois policymakers have yet to tackle the issue head-on.

The Right to Read bill takes a three-pronged approach: It would push the state school board to create a list of evidence-based reading programs and develop a menu of support, training, and grants for districts who want to adopt them; require an evidence-based reading assessment for teachers seeking relevant licensure in the early grades; and kick off a process of creating a statewide online training module for current preschool and elementary teachers, including those who work with students with disabilities.

“Some states have been heavy-handed about what they’ve mandated,” said Jessica Handy, policy director for the advocacy group Stand for Children Illinois, which backs the bill. But Illinois doesn’t have a deep bench of specialists trained in scientifically backed instruction, yet, so the goal, she explained, is to “empower people from the ground up.”

Both the House and Senate versions of the bill easily passed committees and have headed to the respective floors for debate this session.

But the bill has come up against some pushback, including from the state superintendent and state school board, which currently oppose the effort. Jackie Matthews, a spokeswoman for the state board, said that officials there have been regularly meeting about the legislation but have “significant” concerns that the effort leaves out English Learners.

“Research has demonstrated that effective literacy models must be comprehensive, culturally responsive, and inclusive of foundational skills,” she wrote in an email, “but not limited by them.”

She said the board is already working with counterparts in higher education to develop a training module or microcredential around evidence-based literacy instruction for existing educators.

Lightford, the bill sponsor, said the state needs a more comprehensive approach. She recalls how, working in the Secretary of State’s office in the 1990s, she encountered adults who couldn’t read the questions on the driver’s license tests. After one older trucker repeatedly failed and admitted the problem, Lightford helped introduce an oral exam option.

The experience stuck with her.

“This is something we should have had on the books a long time ago,” Lightford said.

Poor reading skills are an issue for many children, she said, and the data show the problem has an economic ripple effect.

“Poor literacy can hurt a student’s success,” Lightford said, “but it transfers into their adulthood and causes them all kinds of issues with gainful employment.”

‘Bigger words get me sometimes’

The Lawndale reading lessons take place in a brick legal center next door to the apartments where, in 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. moved in for a time to call attention to Chicago’s fiercely drawn lines of segregation. The original tenement where King lived has been torn down and newer apartments constructed in its place.

Fifty-six years later, the teens in the program next door still confront lines and borders and the legacy of segregation.

The Redwood program budgets the cost of Lyfts to ferry the students to and from classes, since getting to the legal center requires crossing a major gangland boundary, a reality that can threaten participation. The students describe education trajectories full of under-resourced schools, crowded classrooms, and tepid acceptance by adults of their paths in life.

“We have to be very honest and say that we as a society have become callous to our young people failing,” said Kareem Weaver, the founder of the Oakland, Calif.-based group Fulcrum who has become a national advocate for the science of reading. “People look at the violence, and the despair and the seeming dysfunction that’s out there, and if you do a root cause analysis, at the end of it, what do you think is the reading level of the kids out there?”

“That’s not just a question for young people,” Weaver added. “It’s a question for adults: Have we given up on our children?”

Moses, who is 18, struggled to read from early on but his problems were overshadowed by violence on his block and stints sleeping in a car or doubling up with other families. During his lifetime, waves of education policy swept through the system with lofty names like Race to the Top and Renaissance 2010 — but they did little to help him move ahead.

During his elementary years, he attended two different schools, was socially promoted twice to catch up with other students his age, and held back once. He says his mother’s requests for a special education program, or IEP, around that time were ignored.

There was more attention on behavior than learning, he said, and he felt nervous about asking for help.

“I was able to get through it, but it was hard,” Moses said. “I had to start asking for help and sometimes I had to do it myself and get it wrong and fail.”

His classmates also landed in the literacy program through a similar combination of poverty, personal tragedy, and systemic neglect.

Jade, who did not want her real name used, said that after her mother died during her elementary years, teachers gave her extra emotional support but kept passing her to the next grade.

After a run-in with the legal system, a caseworker referred her to the program.

“It’s the only thing I need – I need to read and count my numbers,” she said. “I don’t need the other seven or eight classes I take at school. I go in, and I tell them, I’m not in the mood. I’m not going to argue with you. I’m going to just sit down, and look, and watch you talk.”

She likes the Redwood program better than her Little Village high school, where she’s failing two classes.

Hicks, the Redwood teacher, “is helping us understand the words we need — and she explains it way better,” she said. The method of breaking down words and sounds makes more sense. “Bigger words get me sometimes, and sometimes I don’t understand them.”

Another participant, who’s 17, said that when he’s reading, he sometimes trips up on certain words — they come out differently when he says them aloud than how he pictures them in his brain. He can’t recall ever having been tested for dyslexia or another reading disorder.

He also was recommended to the program by a case manager after getting in trouble with the law, but thinks it’s a good use of his time. It keeps him busy, he said, and when it comes to reading, “things are clicking a little more than they used to.”

He’s been struggling with attendance at the small alternative high school he attends nearby, due to issues outside of school that he doesn’t want to explain in detail.

In October, the program had eight students attending regularly. By February, all eight are still there, showing up even when their schools are shuttered for five days after winter break due to a standoff between the teachers union and district leadership. The program’s classes have moved from the gym, which was hard to keep warm in the winter, to a cozy meeting room with colorful murals.

The teens are adding new words quickly now.

Slate. Frustrate. Cashmere.

Hicks defines cashmere for the group, but she doesn’t have to define frustrate. Someone has pilfered some of the reading group’s supplies and stolen some of the magnetic boards used for manipulating letters and sounds.

“Fun fact,” Feriante tells the group during a quick snack break, “that’s now 60% of the words in the English language that you can read and spell.”

Two students have become or are about to become fathers. High school graduation hovers in the not-so-distant future, a question mark for some of the seniors and far from a certainty.

But the guarantee of small group instruction, transportation help, small weekly stipends, a larger end-of-the-year sum – and heaping amounts of Hicks’ grace — keep the reading program going strong.

Heather Saunders, a case manager at Lawndale Christian Legal Center, which provides legal services and case management for young people ages 24 and under, said it was critical to the program’s launch that the teens be incentivized to attend, so they prioritized the sessions.

“Education gets disrupted because of jail time, safety issues, suspensions — most of our young people are way behind,” Saunders said. “There are reasons that are school-involved but also reasons that are not-school involved.”

She looks forward to the program’s spring graduation ceremony. Last spring after the pilot’s first year, students brought their families and there was clapping, balloons, pride, tears.

“Our young people never get called out for their greatness.” She pauses. “A lot of their needs have gone unmet for so long.”

On this February evening, break time is nearly over, the students have stocked up on Takis tortilla chips and Capri Suns that Redwood organizers supplied. Some are updating the adults in the room about efforts to get high school credit for the program.

Hicks, who has more words to review, calls the class back to order.

“Let’s move on, beautiful people.”

Cassie Walker Burke is the Chalkbeat Chicago bureau chief. She covers early learning and K-12. Contact Cassie at cburke@chalkbeat.org.