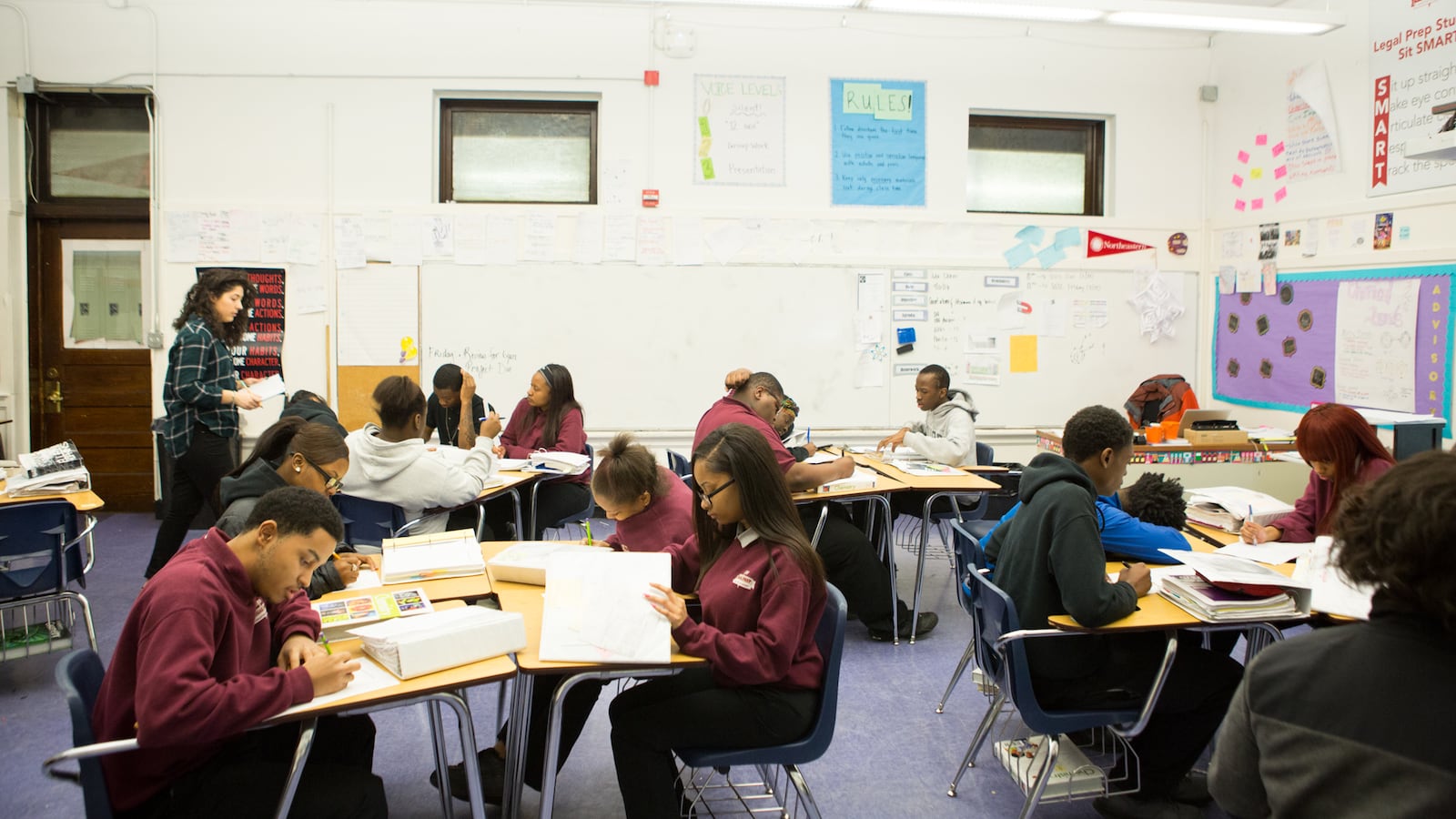

When teachers at Legal Prep Charter Academy returned to school in August, they discovered a new central air system, freshly painted red hallways, and something else surprising — a professional development seminar called “Restorative Justice 101.”

The course, which coached them in a new approach to discipline, was part of a monumental shift away from exclusionary discipline — spurred by renewed anti-racism protests, a feeling that the old system wasn’t working, and more scrutiny of charter discipline data by Chicago Public Schools.

Founded on the concept of justice, equity, and diversity, Legal Prep previously had a dubious distinction: It suspended students at a higher rate than any other school in Chicago and issued 13 expulsions during the 2019-2020 school year, meaning almost one out of every 20 students was expelled.

But this fall, teachers were being trained in restorative practices — responses to rule-breaking that focus on compassion and reducing repeat offenses — an effort that, assessed 22 weeks into this school year, appears to be making a difference.

So far this year, three of the about 300 students on the charter’s West Garfield campus had been suspended, said Legal Prep co-founder and current principal Sam Finkelstein. And Legal Prep’s director of culture, Joseph Williams, said as of mid-January, there hadn’t been a fight on campus since Nov. 1.

“The building feels less tense and feels much more comfortable,” said Finkelstein. “And I feel like it does equal a happier student.”

Over the past decade, Chicago has been one of many public school districts that have taken a hard look at discipline practices, but the city’s 100-plus charters have largely been left to their own devices.

Even during the 2019-2020 school year, when in-person learning was abruptly truncated by the coronavirus pandemic, the district’s charters issued an average of 130 suspensions per 1,000 students. (Students can be suspended multiple times). That rate is nearly five times that of non-charter schools in Chicago, according to new analysis of disciplinary data obtained online from the Illinois State Board of Education and Chicago Public Schools.

Of the schools in Chicago issuing the highest number of expulsions in 2019-2020, eight of the top 10 schools were charter schools, according to data from the Illinois State Board of Education. In 2018-2019, all 10 were charters. Legal Prep was on both of those lists.

Analysis of the data also shows that, despite a push for more restorative practices, change has been slow for both district-run schools and charters.

The school district is taking notice. At the January school board meeting, officials argued that shorter-term charter renewals of two to five years, instead of the state-sanctioned 10, will offer more opportunity to scrutinize the number of suspensions and expulsions. Charter advocates have pushed back on the shorter renewals, arguing the district needs to find a better way to balance accountability and the conditions charters need to plan and thrive.

CPS asked Legal Prep to provide more information on its disciplinary practices with its renewal application, according to documents obtained through a public records request. The district noted the school’s high rate of suspensions and expulsions, as well as the length of the suspensions issued to students.

Legal Prep did not dispute the concerns raised by CPS. In its renewal application, the school said it would not try to “justify” the discipline data but instead work to change the school’s discipline policy.

Still, Finkelstein was among the charter leaders and parents who testified before the board in favor of longer terms, citing Legal Prep’s discipline overhaul as one reason for the standard renewal. Other community members also spoke at the meeting in favor of its renewal.

In the end, the board voted to renew Legal Prep for a shorter two-year term.

The shorter renewal term “is our only tool we have as an operator, by virtue of the way charter schools are administered in the state of Illinois and for Chicago,” Board member Elizabeth Todd-Breland said. “It is also about saying, no, you will not expel a kindergartener in the city of Chicago.”

Chicago charter schools follow own rules

Excessive discipline is not just a charter school issue. Studies have consistently shown that students of color, and particularly Black boys, are disciplined more frequently than their white peers, and are often disciplined for violations that their white peers are not. In traditional public schools in Chicago, schools with larger white populations were less likely in 2019-2020 to suspend or expel students than schools with schools with more Black students, the data show.

The three district-run public high schools with the highest percentage of white students — Taft High School, Lane Technical High School, and Walter Payton College Prep — issued an average of four out-of-school suspensions per 1,000 students in the 2019-2020 school year.

By contrast, the three traditional public high schools with the highest percentage of Black students for which data was available — Hyde Park Academy High School, Simeon Career Academy High School, and Little Black Pearl Art and Design Academy — issued an average of 62.5 suspensions per 1,000 students the same year.

Disproportionate discipline in charter schools only furthers this racial imbalance, since charter schools in Chicago — which are publicly funded by privately managed — are overwhelmingly non-white.

Overall, data show fewer students are being expelled or suspended at schools citywide. That decline is the result of a prohibition in 2006 of “zero tolerance” policies that require staff to suspend or expel students as a consequence for certain offenses.

Charter schools are not required to follow every policy regulation set by Chicago Public Schools, since they are independently run. Still, discipline in charter schools in Chicago also decreased in the last five years. In 2015, the average number of out-of-school suspensions issued by Chicago charter schools per 1,000 students was 274. In 2020, it was 130.

Chicago Public Schools has made an effort to work toward restorative justice practices and away from exclusionary discipline. In 2017, the CPS Office of Social and Emotional Learning published a toolkit for restorative practices.

Starting last year, CPS gave local school councils the option of whether to keep or get rid of school resource officers, the Chicago police officers stationed in schools. Thirty-one high schools voted to eliminate one or more officers this summer, with some opting to use the freed-up budget money for restorative justice training for staff and others.

Chicago Public Schools also released a new anti-bias framework this summer that, in addition to outlining new procedures for investigating bias-based incidents, includes a section on “community accountability” — that is, more “healing” responses to harm, according to CPS, instead of punitive measures such as suspensions and expulsions.

As part of this framework, the Office of Student Protections says it is providing guidance to public schools — including charters — on reducing bias and less-punitive discipline practices, though they have not released more details publicly. The district said it is preparing to launch more initiatives related to this framework throughout the year.

Some charter schools are also rethinking discipline. Noble Network of Charter Schools scrapped its controversial demerit program, where students were punished for small infractions, and those demerits would accumulate into a higher punishment. The network also replaced its student code of conduct with “The Noble Community Pact,” according to a spokesperson for the network.

The pact uses restorative justice practices, including peer mediations and wellness spaces, in response to students’ misconduct instead of exclusionary discipline. While Noble couldn’t provide data on suspensions and expulsions from this year, the spokesperson said the network is hopeful that the new community pact will help it in its new push to become an “anti-racist” organization.

At Legal Prep, Finkelstein, Williams, and other administrators have restructured the disciplinary code. Instead of setting suspension or expulsion as a punishment for certain offenses, such as fighting, students being disciplined have to engage in a mediation process with a member of the school’s counseling team to get at the root cause of the issue.

Suspension and expulsion are not off the table, but the school now views those punishments as last resorts, Finkelstein said.

Over the summer, Legal Prep also hired several new staff members, and Finkelstein said they specifically sought out candidates who were interested in restorative justice. Indeed, moving to restorative justice requires a massive cultural shift — one for which not everyone is prepared.

Lofty ideal leads to a culture of strict discipline

At Legal Prep, which was founded in 2012 and claims to be Chicago’s only legal-themed school, the original campus philosophy was “high expectations, harsh consequences.”

That lofty ideal led to harsh punishment: Staff suspended and expelled students frequently, with the hope that the discipline would act as a deterrent to problematic behavior. Similar to Noble Schools, Legal Prep would punish students for small infractions, such as talking out of turn, in order to try and deter students from committing larger infractions. But Finkelstein said that this method wasn’t successful.

The school, which is about 99% Black, issued 190 out-of-school suspensions during the 2019-2020 school year. Community organizers and students say the harsh discipline tactics make students less engaged with school and feel unwanted.

Legal Prep has had other troubles. The charter was named as a defendant in two federal lawsuits filed on behalf of former students, alleging that a former Legal Prep staff member repeatedly sexually assaulted two minors on campus from 2017 to 2018. Those cases, which were filed in the U.S. District Court for Northern Illinois in 2019, are ongoing. Finkelstein did not comment on the suit.

In addition, the school has struggled with administrative turnover and finances, the school’s renewal application shows. In 2018, the school completed renovations to its property required by the school district. These renovations drained the school’s coffers, preventing it from taking on other expenses for the last few years.

Ken Ayers arrived at Legal Prep in 2015 after a difficult freshman year at a different charter school. Ayers, who is now a senior at Illinois State University preparing for law school, found a lot of value in the school’s law programs. And as a star student, he didn’t often get in trouble, but watched as his peers did.

Ayers said he often saw students at Legal Prep “self-medicating” with drugs or alcohol or acting out and fighting in school. West Garfield Park is one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in Chicago. But rather than just disciplining students for such behavior, he said, the school should have been more compassionate.

“I [saw] a lot of reactive behavior, but not a lot of proactive behavior,” Ayers said. “They need to do something to not only connect with the students, but actually connect to the families as well, because the student is not the only person going through the trauma.”

Ayers transferred to a private school in East Garfield Park after one year, looking for more challenges academically. This summer, he had internships at three different law firms in Chicago, and took the LSAT in August.

In response to concerns such as these, Legal Prep staff implemented what they’re calling the “breather system,” according to Finkelstein. When a student is acting up in class, the teacher will call a member of the school’s counseling or discipline team to pull the student out for a few minutes.

The student can talk to a staff member for a few minutes about what’s bothering them. They can then return to class, having vented and calmed down.

The school has also started using peace circles and mediation — mainstays of restorative justice practices — to intercede when students get into more serious trouble, such as getting in fights. Finkelstein says they often try to get the parents involved in mediation, as well as teachers and other students who may be involved.

Mediation sessions often resolve whatever issues the students have, and the students aren’t punished for their actions afterward. Students are also sometimes directed to anger management sessions with a school counselor.

Under the new restorative justice program, students are less likely to continue to misbehave after completing a restorative justice process, he says. And the number of suspensions has been slashed to single digits.

Joseph Williams, director of culture at Legal Prep, says students are happier now with the restorative justice process. He says students have developed trust in the restorative justice process and have started asking for mediations before acting out.

“The upperclassmen do seem happy with the changes,” Williams said in an email. “The 9th and 10th graders have never known another way, since we were remote all of last year, and they are definitely bought into the system.”

Williams also sat on Legal Prep’s hiring committee over the summer, and said the committee spent significant time in interviews ensuring new teachers would be a good fit with the school’s changing culture. Most returning teachers contributed to the design of the new restorative justice system.

Some teachers were anxious about switching to the new system because they were worried about an uptick in violent behavior, but those worries have been assuaged by the results they’ve seen so far, according to Williams.

New approach is part of push to keep children in school

Next door to Legal Prep, Rev. Marshall Hatch, Jr. is paying close attention to the changes at the school.

Hatch is one of the pastors at New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church in West Garfield, which occupies the building next door. Out of the same building, he also runs the MAAFA Redemption Project, an initiative that provides resources and life skills to at-risk young men between 18 and 30.

Hatch completed an internship with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights while in graduate school and studied the way school-to-prison pipeline can funnel public school students, particularly Black students, into the criminal justice system. Studies have shown that excessive discipline contributes to the pipeline.

“If a student is not in a school building or the classroom, where are they?” Hatch said. “Students who are suspended at higher rates or expelled, those students are more likely to have early involvement with the criminal justice system.”

In communities with a heavy police presence, students who are out of school are more likely to come into contact with police.

Experts agree that excessive discipline is detrimental to students’ self-esteem. In addition to missing out on what they would learn in class, multiple suspensions and expulsions can make students feel unwelcome and unwanted in school.

“Expulsion is not great for children,” said Dr. Terri Sabol, a professor of child development in Northwestern University’s School of Education and Social Policy. “It sets them up to feel disconnected from school, for thinking that they don’t belong. And it can have long term effects on their development and their connection to school.”

Under Legal Prep’s new restorative approach, students miss far less class time than they did previously. In fact, the system is designed to minimize the amount of class students miss, Williams said.

“When kids miss school, they have a hard time catching up and following along, and that only increases the likelihood of them acting out,” he said.

Students expelled from traditional public schools typically can’t attend another CPS school for at least a year. Instead, they are automatically enrolled in an alternative program, according to a statement from Chicago Public Schools.

Charter schools must notify CPS when a student is expelled; district officials then review the student’s case and decide whether or not the student can enroll in a district school or an alternative program.

This kind of disruption can deter many students from returning to school at all, even though state law requires that students stay in school until they are 17, according to Michael Hannan, an administrator with the Alternative Schools Network, a nonprofit that works with students who have left school.

Still, there are often challenges with implementing restorative justice after students are accustomed to exclusionary discipline.

Restorative methods depend on acceptance from everyone, Hannan said.

Because the students with whom he works at the Alternative Schools Network have usually already dealt with exclusionary discipline, he and the network embrace restorative justice practices. But not all families or even students buy into them.

Hannan said that some students don’t want a restorative justice process or are suspicious of a new system. To get students on board, schools must be consistent in their messaging and discipline, Hannan said.

Hannan also emphasizes that restorative justice doesn’t mean that students aren’t held accountable for their actions.

“It’s not ‘you can do whatever you want, and you get to be back in the classroom.’ That’s just bad practice,” Hannan said. “A good restorative process involves hard work, involves conversations and involves the support of your peers. But that’s because, if you have a real restorative justice practice in your school, you build that network of support.”

While Finkelstein recognized that not everyone would embrace Legal Prep’s shift to restorative justice, he said he’s hoping the change will teach students more about community.

“There’s a real opportunity for us to help kids understand the importance of this work, help kids understand that this is not just about them individually, this is about the collective,” Finkelstein said. “[It’s] about all of us in the school as a community, making this commitment to each other, to our school community, that we’re going to be a place where everybody can succeed, where people can make mistakes and still be successful.”