When schools shut down because of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, Chicago music teacher Trevor Nicholas found himself at his piano composing songs for his students to connect with them at an uncertain time and help them navigate their pain. That work ultimately earned Nicholas a Grammy nomination.

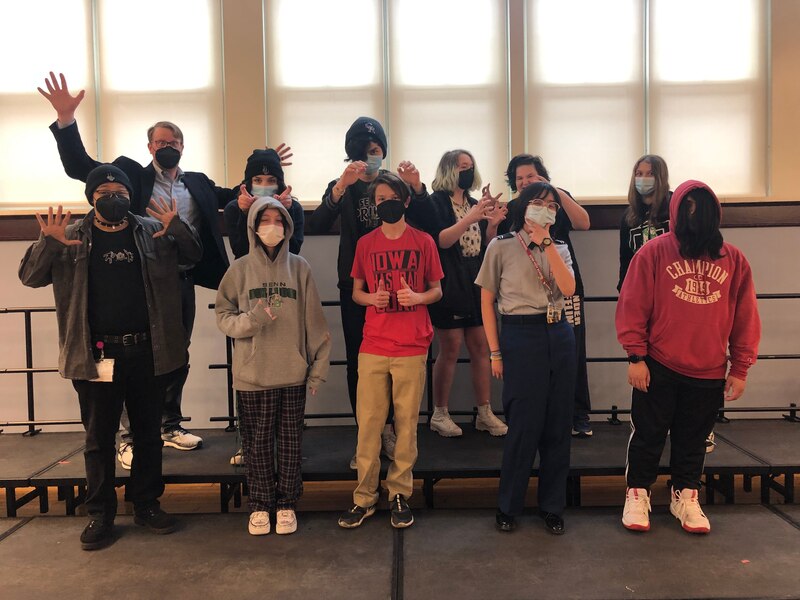

He envisioned a project that could be a conduit for healing, not just for the Senn High School community but also for people around the world who were isolated trying to process the unfolding trauma. Through a computer screen, the music teacher of 13 years shared with his students his composition and some lyrics for “Who Will Carry Me?” an original song that would ultimately be made into a music video featuring his students.

“I found so much healing and peace at the piano, expressing myself through music,” Nicholas said. “As a music teacher, it’s something I try to bring to my students, the healing power of music.”

By the fall of 2020, Nicholas — in collaboration with his students — brought that vision to life. Next week, Nicholas plans to release a follow-up music video named “The Cave.”

Music as a vehicle for healing has been a part of Nicholas’ life since a young age. After being diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, he used a wheelchair while in the fifth grade. He spent hours at the piano during that time, and music became his companion. Now, as a teacher, he hopes to inspire his students to see music as a change agent to mend after two tumultuous years.

Over the past six years, his student ensembles have premiered works at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Harris Theater, and Wrigley Field. He has partnered with arts organizations to bring more than $300,000 in grants, donations, and free music lessons to his Chicago Public Schools students.

Nicholas was among 10 teachers nominated for Educator of Year at the 2022 Grammy ceremony. (Stephen Cox, a teacher from Texas, won the Grammy, the awards ceremony announced on Thursday.)

Nicholas spoke recently with Chalkbeat about encouraging his students to create, giving them opportunities like those he had as a young musician, and reminding them that they are enough.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

I was supposed to major in physics, but one month before I went off to college, I realized that I had spent my later years of high school entering people’s lives with my own piano improvisations. The music — created out of my pain and trauma — built connection and allowed healing to happen. I thought: Wouldn’t it be neat to become a teacher and teach students to heal those around them by also connecting with sound?

After graduating college, I went to Los Angeles and met a bunch of amazing people that were passionate about composing and film scoring. I met J.A.C. Redford, a composer, arranger, and orchestrator. He looked at my music and compositions. I shared my story, my connection with music, my ideas on wanting to use music as an agent of change. He laid out the challenges of the industry and said, “You could probably do a lot more good if you went back and became a choral director and continue to write, continue to compose.”

I came back and jumped right in. Here I am, 13 years in, teaching music and choir in Chicago.

What are you doing to meet your students’ needs following two disrupted school years and the trauma COVID brought with it?

We know that trauma plus isolation equals traumatization. We combat long-term traumatization by giving students insulating factors.

For the “Who Will Carry Me?” one student wrote the last verse. We sat and arranged it live. Students recorded their contributions individually, and then we brought it together. This experience gave us a community and an opportunity to create art together while we were separate. It also allowed for us to turn that healing we were going through outward so that that light can shine and uplift others.

Even for those who weren’t able to send a video, they would get excited because we did it as a community. It anchored the whole community. So, we decided to follow that music project with another called the Cave, which aims to address the racial and mental health trauma that students were experiencing. We spent months working with a guest artist Sharon Irving, an America’s Got Talent contestant from the South Side of Chicago. Irving’s grandfather marched alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma. We were anchored in history.

We are also launching a new initiative, electro acoustic pathway, where students can learn how to use a variety of recording equipment used by audio producers and engineers to formally study and develop as artists and healing agents. It also provides an opportunity to understand the different types of jobs beyond the stage available in the music industry.

Can you explain how you bring your own music background into your classroom and how you help students process whatever they might be going through?

During the beginning of the pandemic, I was finishing my master’s degree, and my final project was to write music for my students that they would enjoy and respond to specific traumatic events in our learning community. When we went into quarantine, I’d already released a few of those pieces with my students, and we were able to continue that thread that started there.

The process resulted in the creation of “Who Will Carry Me?”

I also do a film music unit with my students where we talk about how you can rewrite a movie scene using music. We then wipe the audio from a movie scene to change and shift things through music.

We make our art in the large ensembles, but I also encourage them to make their own art. Sometimes it’s weird to have somebody touch your art or move it around; it’s like somebody comes in and paints on your canvas, and that just doesn’t always feel right. A lot of the way we structured our music program is to have some time to work on your own artistry. I share my story and the difficult time during my youth struggling with depression. Hopefully, my ability to give grace and have patience help motivate my students on a daily basis.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your class?

The sum total of all the things that happened in the last two years has created a community mental health crisis. And how — even with something you love, like music — do you stay motivated each day?

As a student, how do you come in and deeply analyze lyrics or a piece? Or find metaphors and the alliterations as you’re writing your own lyrics? How do you take time to do that and focus when you’re in such a hurt place and you’re trying to heal? I don’t have that answer yet, but that’s my number one.

How can I motivate my students? Not so that they can produce something, but so that they can genuinely enter the process of music each day. Even if they’re going slowly, they’re still going somewhere. But what we’re seeing is, students just shut down so easily. And they’re not rude about it. But they’re having trouble having that internal motivation. There’s some healing to be had.

Can you tell me about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today?

My experience in school was filled with a lot of loss. We had a lot of really, really tragic things happen in our small town in Northern Minnesota. My group and individual experiences performing music buoyed me through those really difficult times. Our music teachers worked really hard to give us big opportunities and take us to big cities to perform. Those bus rides making music with bandmates were some of the best memories. We started talking about something and somebody busts out an instrument that’s not too loud. And during [sports] games, we would improvise playing some jazz and the blues. We had so much fun.

As a teacher, I give my students space to work individually, to jam out, and have some fun. I also make sure that large ensembles have performing experiences where when they walk off the stage they can say: “Wow, we did a really great job with that.” We have received invitations to premiere a youth opera at the Chicago Lyric Opera, Millenium Park, Chicago Harris Theater, and perform for the Cubs. I know those big experiences anchored me as a youth, and I know how valuable it’s going to be to my kids.

What’s the best advice you’ve received, and how do you put it into practice?

One of my dear mentors and friends, Dr. Angela Kasper, said to me and my grad school classmates just before our last performance: “Who you are, right now, is enough.”

At the moment, many of us are re-shifting or changing our lives as we’re trying to move into that fully post-pandemic time. We’re wondering about our work, about the choices that we’ve made. Our students are wondering: Do I belong here? Do I deserve to be in this music program or this International Baccalaureate program?

Since this advice was handed to me a few years ago, I’ve been very intentional about handing that to my students and reminding them that even if they struggle with an assignment: You are enough just as you are.

You have a busy job, and this is a stressful time. How do you take care of yourself when you’re not at work?

I love being on my bike, and I love swimming. I think I got up to about 130 miles a couple of weeks ago in one week of cycling. A few times a week, I swim with this amazing team called the Chicago Swedish Fish. But more than that, I shut off my phone. I find my boys and my wife, and play, and just spend time together without any devices.

Mauricio Peña is a reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering K-12 schools. Contact Mauricio at mpena@chalkbeat.org.