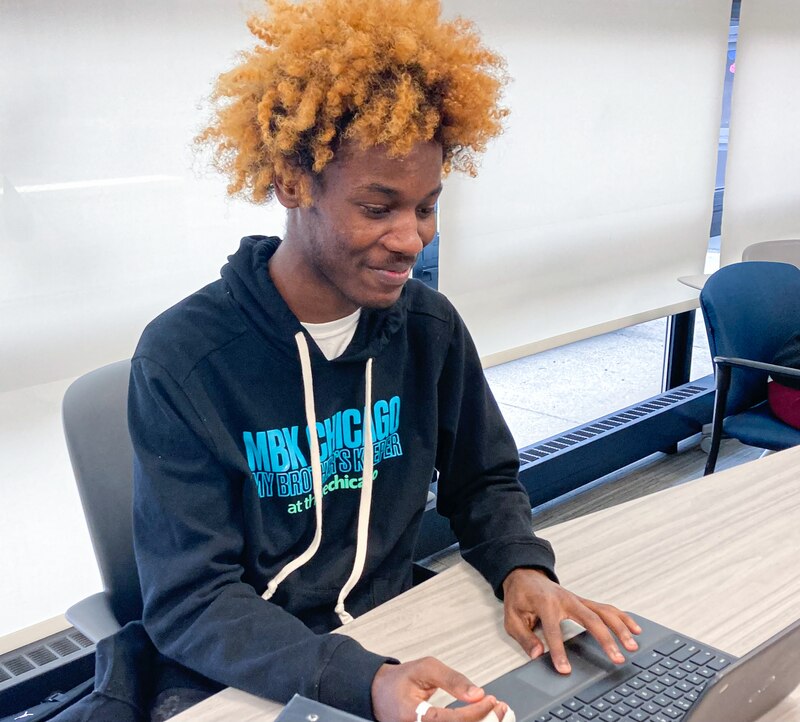

The question came when Khalil Cotton least expected it. He was in summer school, after falling behind at Dyett High School for the Arts during the upheaval of COVID and virtual learning his junior year.

Then, out of the blue, the school’s principal, Cortez McCoy, pulled him aside and asked: Would he consider becoming a teacher?

Khalil thought back to educators with whom he’d bonded in middle school: A math teacher who made the subject fun even for struggling students. A computer science teacher who cultivated a passion for coding in Khalil and became a “big brother,” that rare person in front of whom the teen allowed himself to cry.

Both were Black men.

With McCoy’s encouragement, Khalil, now a rising senior, joined a pilot program launched last fall at Dyett and two other Chicago high schools to cultivate a new generation of Black and Latino male teachers. About 80 seniors are taking an Intro to Urban Education class and sorting through their career goals, with plans to offer more mentoring after graduation.

The pandemic exacted a heavy toll from boys and young men of color, widening racial and gender disparities in academic outcomes such as graduation and college enrollment. Some advocates and experts believe that attacking a long-standing shortage of educators who look like these teens is a key solution, given evidence that exposure to male teachers of color increases boys’ odds of graduating and going to college.

In Chicago Public Schools, students of color make up about 90% of the student body, 16% are Black boys, and almost a quarter are Latino boys. Yet fewer than 4% of the district’s teachers are Black men, and fewer than 5% are Latino men. That compares with fewer than 2% for each group in Illinois districts overall, where students of color make up slightly more than half the enrollment.

The pandemic and the country’s post-George Floyd racial reckoning have given new urgency to efforts to recruit and retain male teachers of color, with more buy-in from school districts, which have often let nonprofits take the lead. But the push to grow the ranks of these teachers face hurdles, including schools that put too much pressure on young Black and Latino educators to be role models and disciplinarians for boys of color.

Khalil, the Dyett High senior, for one, says he is not daunted.

“I want to be there for students in that way,” he said. “I want a kid to say to me one day, ‘Thank you! You changed my life.’”

The pandemic widened disparities — and spurred new urgency

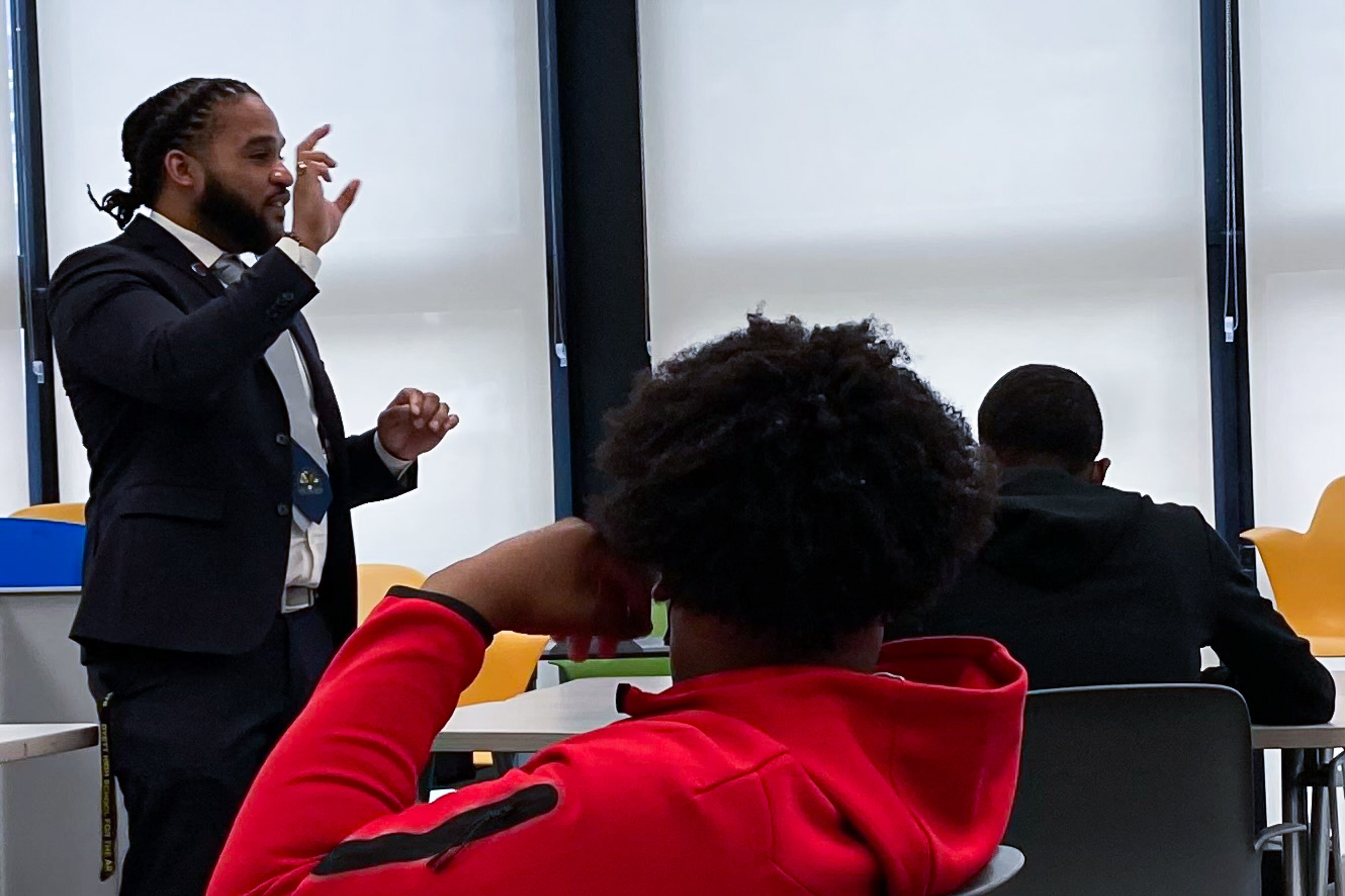

In a Dyett classroom recently, McCoy reminded seven students of their upcoming capstone assignment: Pick a subject they are interested in and teach a class. They could put together a PowerPoint presentation, have a conversation with peers-turned-pupils, or — as one of the students, Jamal Davis, vowed to do — make the class get up and dance. The idea was to get a small taste of shaping young minds. Over the whiteboard, a stenciled sign read, “You Get What You Work For, Not What You Wish For.”

“You all will be activists in the classroom,” McCoy said. “You being in front of those students every day will bring about social change. It’s not common. The fact that you all are about to graduate is not common. You are bringing about social change already.”

McCoy first found out about the pilot project last summer when the nonprofit Thrive Chicago, which administers former President Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative locally, approached him about piloting an effort to steer more Black and Latino boys toward careers in education. At Dyett, more than 95% of the roughly 580 students are Black, and more than 80% qualify for subsidized school meals, the federal measure of poverty.

For McCoy, who grew up poor in the South Side’s Roseland neighborhood, the idea resonated instantly.

“Education was always presented to my family as a way out,” said the former math teacher.

Although he expected a new Intro to Urban Education class would be hard to juggle with his principal duties during a year that has tested school leaders, he said, “I instantly knew this was a class I wanted to teach as a Black man.”

At Thrive, Yaseen Abdus-Saboor, the My Brother’s Keeper coordinator, said the idea for the project predates the pandemic. At a summer 2019 summit My Brother’s Keeper hosted in Chicago, teens and young men of color told organizers they wanted more school-based activities and classes that would help them forge a sense of purpose. Abdus-Saboor and others on his team also pored over recent research showing that exposure to Black teachers — particularly male teachers — in the elementary grades significantly decreases the odds of dropping out and increases the likelihood of pursuing a college degree for Black boys.

The pandemic only raised the stakes: Here in Chicago, according to a Chalkbeat analysis, last school year widened already marked disparities in attendance and grades for Black and Latino boys. Nationally, data on test scores and college enrollment also shows a disproportionate impact on male students of color.

The Thrive pilot is the latest in a string of recent efforts to draw more men of color to teaching, often starting in high school or college.

In New Orleans, a program called Brothers Empowered to Teach has gotten recognition for steering 75% of its 50 original participants to teacher training programs — and supporting them through college and the make-or-break early years on the job. A TED Talk by its co-founder Larry Irvin Jr. on retaining Black teachers has drawn more than 1.5 million views.

More recently, University of Illinois Chicago started a program for would-be male Black and Latino teachers named Call Me MISTER, which offers scholarships, mentoring and help with finding a job. In Chicago, the Thrive pilot has built on a district program called Teach Chicago Tomorrow, which supports high school students interested in education jobs more broadly. That program is among efforts the district credits for helping it increase the portion of Black and Latino new teacher hires from about 30% in 2019 to 45% last year.

Travis Bristol, an expert in educator diversity and retention at the University of California at Berkeley, says it’s refreshing to see more school district buy-in for efforts that were traditionally often backed by philanthropy. (For now, Thrive covers the cost of the program in Chicago.) He points to a resolution the Los Angeles Unified School District board passed earlier this year setting goals to increase the number of Black teachers and leaders in that district, the country’s second largest.

But retaining fledgling educators remains a challenge. In studying a New York program called NYC Men Teach, Bristol found that school leaders who understand these teachers are key. Male teachers of color are more reluctant to seek out guidance and support from their colleagues and principals than other new teachers.

“The principal has to be intentional about asking these novices if they need help,” Bristol said.

Another issue is that schools often place extreme pressure and unreasonable expectations of male teachers of color navigating the challenging first years of their careers.

“You can’t assume that these men know how to be or even want to be father figures to all Black boys,” Bristol said. “You can’t expect them to come in and fix 400 years of problems for Black boys that they did not create.”

Cory Cain, a dean of instruction at Chicago’s Noble charter network and a co-founder of the Black Male Educators Alliance of Illinois, says he knows this predicament all too well. In his first teacher job in Boston, he was called upon to intervene with boys struggling with behavioral issues — though he had never taught these students and had come to the school because he wanted to teach science, not act as disciplinarian.

“”If we go into teaching, we become a panacea,” said Cain, a former principal at the charter Urban Prep.“We are pushed to solve all the issues and all the problems, which is really exhausting.”

Cain said pressure young men of color feel to contribute to strained family budgets remains a deterrent to going into teaching, with its sometimes unpaid student-teaching experiences and relatively modest starting salaries. And many districts are still lamenting a shortage of male Black and Latino applicants instead of proactively recruiting them on college campuses and among their own support staff members.

“The rhetoric is there,” he said. “But for me, it’s about what people are actually doing.”

Chicago pilot program is slated to expand in the fall

At Dyett during that recent class, McCoy, once a business major in college, told the students the ability to face a classroom of students and state their case clearly translates across professions. In fact, out of the seven teens facing each other across a tight rectangle of desks that day, only Khalil is bent on a teaching career. Two students, including Jamal, are on the fence. The rest have other post-graduation plans.

That’s in line with participants in the project overall, which also premiered at Butler College Prep and Johnson College Prep last fall after an initial plan to pilot it at five high schools was scaled back — in one case, ironically, because a campus was not able to line up a male instructor of color. In a January survey, slightly fewer than 30% of students in the Intro to Urban Education class expressed interest in majoring in education in college, while the rest listed a wide range of other majors.

One takeaway from the first year, said Abdus-Saboor, is that many students already have an idea of what career they’d like to pursue by their senior year. If the program gets to them earlier — perhaps by their sophomore year or sooner — it might influence more to consider education.

“During senior year, we have less time to present educators as a viable career option,” he said.

As Abdus-Saboor works to select seven additional high schools to expand the program this coming fall, he’s looking for campuses that might be open to building a multi-year teaching pathway for students. The program is also reviewing parts of the curriculum that might have been overly wonky to make it “more palatable for high school students.”

The goal of the program was never to turn every single student on to teaching, Abdus-Saboor says. Steering teens to college with a clear sense of purpose is a win — and maybe some will circle back to education down the road.

“We want to plant a seed,” he said.

McCoy agrees that the benefits of the pilot go beyond cultivating future teachers. The curriculum involved a lot of writing, and he saw those skills improve. For McCoy, the class reminded him of the importance of social and emotional support for students and building relationships after he started the year preoccupied with addressing the pandemic’s academic fallout.

For Khalil, who is headed to Chicago’s Columbia College in the fall, the most powerful aspect of the class was pushing students to get to know themselves better. They had to write letters from their 30-year-old selves to their 17- or 18-year-olds selves. They explored what motivates them (in Khalil’s case, his mother’s high expectations) and what they appreciate about themselves (the volunteer work he has done in Chicago and New Orleans).

Jamal, who is going to Clark Atlanta University, a historically Black campus in Georgia, still wants to be a dance studio owner and choreographer. But he says he appreciates the effort to steer more young men like him to education.

He says the support of Black males — from the athletic director to a security guard to educators — has made the campus a more inviting place.

And he also gives high marks to the portion of the class that pushed students to explore their identities.

“Everyone should experience this class — not just boys, but girls too,” he told McCoy. “You have to know yourself before you can bring out the best in others.”

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.