For years, Chicago parent Maria Toribio heard countless stories of school officials quick to call police to deal with minor disciplinary issues. She worried these police interactions would follow students into adulthood and criminalize them.

“Instead of helping our children,” Toribio said in Spanish, “police can sometimes do more harm.”

That’s why Toribio joined a group of Chicago Public Schools parents with a mission: Get police out of schools.

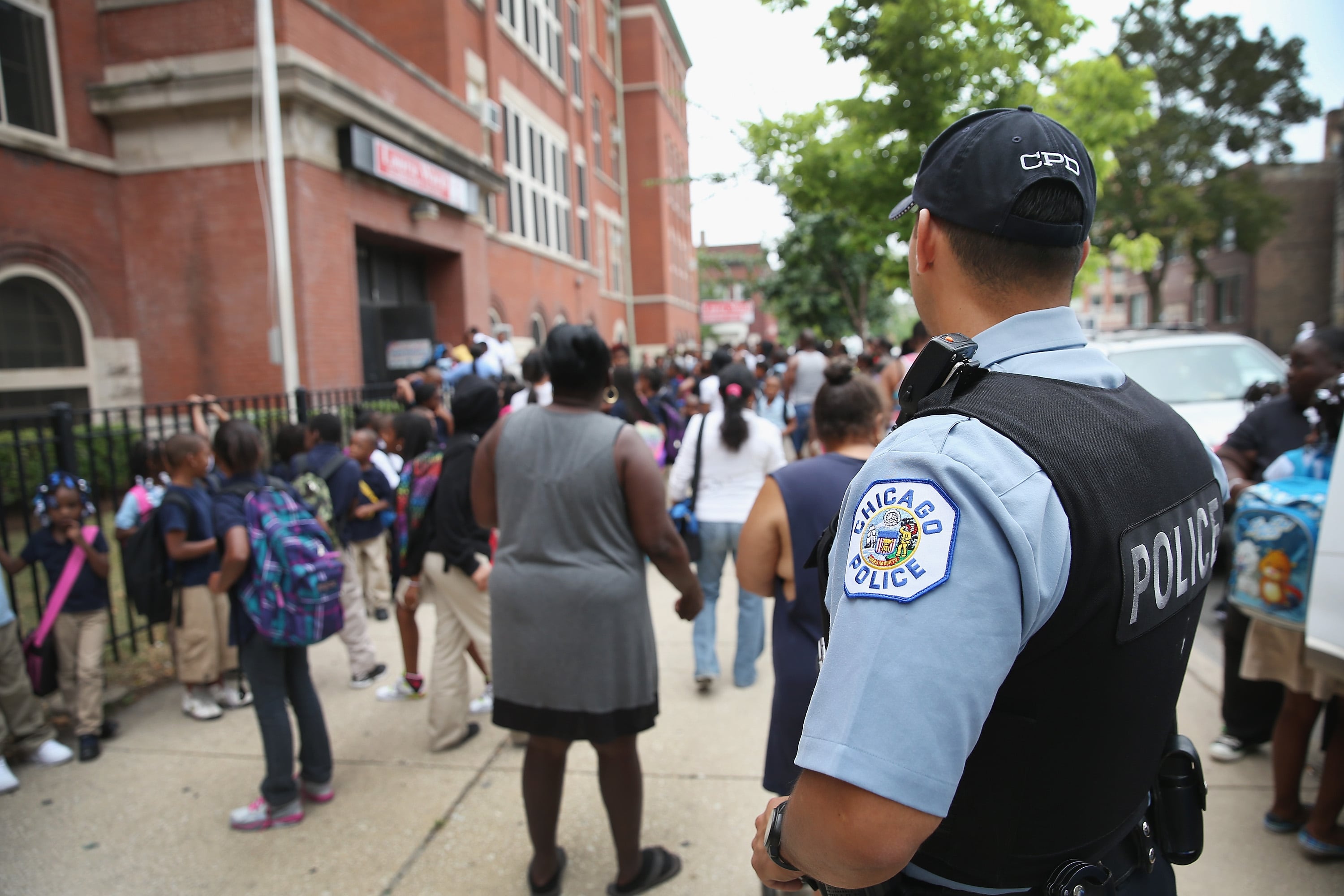

The grassroots movement predated a 2019 federal consent decree to reform the Chicago Police Department, which led the city and school district to rethink the role of police in schools. The district formed a collaborative with local organizations to implement comprehensive approaches to school safety.

But two years after CPS empowered local schools councils to make the decision to keep or remove police, momentum to remove officers from campuses appears to have slowed — and, because the district has released few details about the impact, it’s hard to tell if a different approach to safety is working.

Chicago Public Schools denied Freedom of Information Act requests from Chalkbeat for school-level data on officers, disciplinary referrals, support staff, and funding for safety alternatives. It deferred a request to city hall and the police department.

Removing police officers school-by-school, the latest numbers

Calls to remove police from school campuses had been simmering for years. But in the summer of 2020 — in the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police and the national racial reckoning that followed – individual schools began taking action.

At the time, Toribio was the chair of the Local School Council at Kelvyn Park High School, one of 17 schools that removed officers in 2020.

The following year, another 31 schools followed suit.

But this year, of the 41 schools still voting on officers, Dunbar High School was the only campus to remove both officers, and Carver Military High School and Dyett High School each voted to only keep one of their two officers.

Even with only one school deciding to remove both officers this year, Toribio still sees progress.

“For those of us who have worked so hard to remove police officers,” Toribio said, “this is a small victory.”

Today, there are 59 officers assigned to 40 schools, according to the district, compared to 180 officers in June 2020.

At their July meeting, school board members voted to renew a $10.2 million contract with the Chicago Police Department, shaving $800,000 from its previous contract.

Jadine Chou, the district’s head of safety and security, said that the district has invested nearly $3.8 million toward alternatives to police, with about $2.9 million going to staffing and the rest toward programming and professional development.

Although some parents and politicians argue that police officers make schools safer, Toribio said the opposite, citing the police response in Uvalde, Texas – where more than 400 law enforcement officials waited for more than an hour before confronting a gunman who killed 19 students and two teachers.

“We saw what happened at Uvalde,” Toribio said. “It’s proof once again that the police shouldn’t be in our schools.”

With police officers gone, is a different approach to safety working?

CPS has shared few details on what happens after officers are removed. The district has not publicly shared a comprehensive list of what individual schools are doing to implement safety alternatives, such as peer mediation or peace circles that emphasize strengthening relationships and social emotional learning.

School-level data on funding and disciplinary referrals has not always been available to organizations working with the district on its safety collaborative, said Aida Palma Carpio, an organizer at Community Organizing and Family Issues Power Pac, better known as COFI.

The organizations are supposed to host community engagement sessions and make recommendations based on the input they gather, which schools tailor to fit their specific needs, according to the district.

“We know what schools got rid of SROs, we know how many SROs each school got rid of, yes,” Palma Carpio said. “But we don’t know exactly how much money each school received for their SROs and we don’t know exactly what each school purchased.”

CPS recently updated the information available online about spending on safety alternatives. Last year, schools received at least $50,000 in place of each officer removed. For next year, schools will receive about $80,000 in place of each officer they voted out, with funds going toward positions such as climate and culture coordinators, restorative justice coordinators, social workers, and security guards.

At the July school board meeting, Chou said the district intends to be more transparent with data and is working on ensuring its accuracy.

School Board Vice President Sendhil Revuluri asked how the district evaluates the efficacy of new school safety plans. Chou said data on disciplinary referrals and suspensions, which would be presented at a later time, has reflected a change in culture around safety, but changes have not gone as far as the district had hoped. Data on suspensions and expulsions for the 2021-22 school year was not posted as of publication.

Although the district is committed to adopting more restorative practices, Chou said, safety decisions had to ultimately come from the local community. In discussing the spring votes, she noted that many schools opted to maintain the “status quo.”

“If we had not had the pandemic,” Chou said. “I think we would have had more schools moving forward with this.”

Board member Elizabeth Todd-Breland lauded Chou’s team for continuing to respond to school communities, but argued that schools shouldn’t have officers at all because of the disproportionate criminalization of Black students and students with disabilities.

She was troubled that a majority of schools retaining police are on the largely South and West Sides and serve predominantly Black students, and called it a symptom of the district deferring the decision to the school level.

“If we see a radical inequity in how something is being implemented,” Todd-Breland said, “we do bear responsibility for that at this level — not just at the school level.”

Other challenges to implementing school safety alternatives can be linked to funding, said Carla Rubalcava, managing director of Illinois Programs at Mikva Challenge, one of the organizations partnering with the district on school safety.

Funding is based on factors including enrollment, which has declined in Chicago and other cities across the country. Some schools may not have enough resources to implement the mental health services and other resources called for in recommendations for holistic safety plans, she said.

Students continue efforts toward police-free schools

Even as details remain sparse on implementation, some students have noticed changes.

Cristina Solano, 17, is an incoming senior at Thomas Kelly High School and sits on Mikva’s Safety and Justice Council, which guides its involvement in the district’s collaboration to reimagine school safety plans.

Although Solano never had a negative interaction with her school’s two officers, which Kelly’s Local School Council removed two years ago, she was always afraid to walk by them. Solano was convinced that she would be in trouble, even though she had done nothing wrong.

She also noticed how little the officers interacted with students. Solano always saw them standing by their office in the school, never getting to know the students.

“To me, it was like ‘Why are you here?’ You’re just scaring us,’” she said.

Since their removal, she’s noticed less tension at school. To Solano, the police projected sheer power, while the school’s 10 security guards seemed more approachable.

Some of her friends who were tempted to get into physical fights felt able to go to the security guards, who talked them out of it, Solano said. She said this wouldn’t have been possible with the police.

In addition to police stationed at schools, Chicago Public Schools also employs nearly 1,200 security guards across roughly 500 district-run schools.

Nathaniel Martinez, a rising senior at Theodore Roosevelt High School, has noticed more mental health resources available since that school got rid of its officers. He said students seem more willing to open up to teachers, the dean, or other school staff.

“With police officers around, people always have some sort of stigma that you got to stay silent or stay to yourself, or else you might get in trouble,” he said. “I feel like ever since we removed SROs, or like, removed one at least, students feel slightly safer to open up, whether it’s about mental health or other situations.”

He said grassroots organizing is key to keeping up the momentum for alternative safety practices at Chicago Public Schools.

“So the way we are trying to keep the movement going, keep it alive, is by always trying to engage with the community,” he said.

But shifts toward restorative justice haven’t been felt at all schools in the district, especially at those that still have officers.

Michelle Hernandez, 16, will be a junior this year at Whitney Young High School, which has opted to keep both of its officers. Hernandez is also a member of the Safety and Justice Council at Mikva Challenge.

Despite her involvement in school safety issues, Hernandez said she isn’t aware of conversations about it at Whitney Young. From what she’s seen, few students have paid attention to the issue, and she hasn’t heard much about it from parents either.

“It all just kind of blew past everyone,” she said.

Aida Palma Carpio said COFI already had parents organizing to remove police at many schools that initially voted out officers, making it easier, but they don’t have organizers plugged into every school community.

Parents are worried about many of the same issues – including fighting, mental health, and drug use – across the district, and going forward, it’s important to help educate school communities about the ways these issues can be addressed, Palma Carpio said.

“For many people, you know, the police is the only thing that we’ve known,” she said.

Kae Petrin contributed to this report.

Eileen Pomeroy is a reporting intern for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Eileen at epomeroy@chalkbeat.org.

Mauricio Peña is a reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering K-12 schools. Contact Mauricio at mpena@chalkbeat.org.