Chicago is getting a smaller share of new state education funding this year, in part due to a loss of low-income students and an increased property tax base.

New calculations released by the Illinois Board of Education this morning give Chicago Public Schools $1.75 billion in state money, an overall increase of roughly 1.5% over last year.

But the state’s complex formula for determining how to fund public school districts recategorized Chicago in a way that could mean less state money in the future and a longer road to be considered fully funded.

“They’re still getting money from the state, it’s just less money than they would have,” said Ralph Martire, executive director with the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability and one of the architects of the state law that created the so-called evidence-based funding formula in 2017.

The state is adding $350 million to the billions it is distributing to districts this year. Of that new money, Chicago will get a little more than $27 million of the additional dollars. But district officials say they expected to get around $50 million.

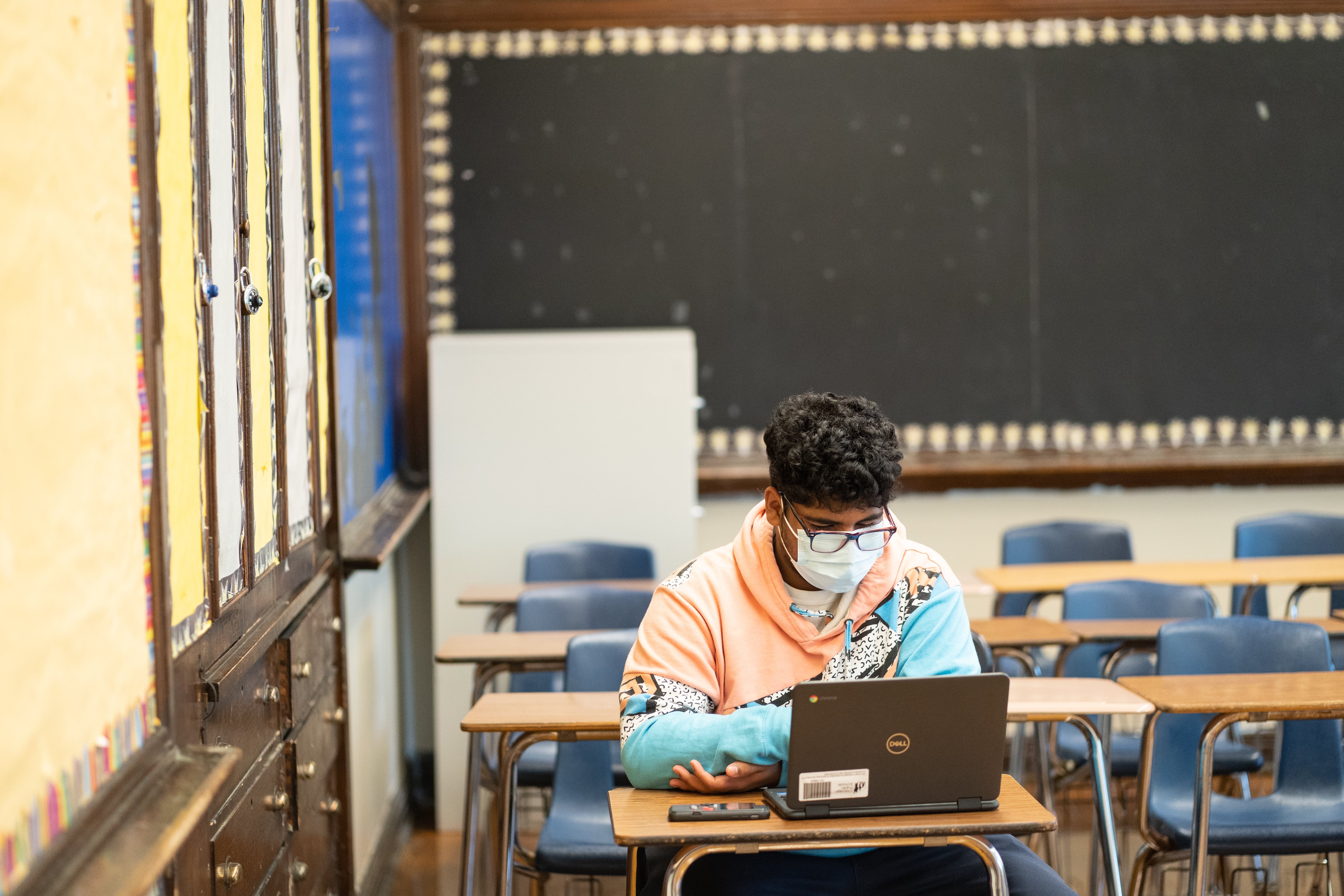

In a statement, a CPS spokesperson said the shift puts more pressure on the district at a time “when our needs have never been greater.”

“Public schools are serving a wider scope of needs than ever before as we emerge from the pandemic and we need all the resources we can get,” the statement said.

The state’s formula for determining how to fund schools looks at a variety of factors, including the percentage of low-income students and wealth of the property surrounding schools. Chicago saw a 4% loss of low-income students and a 3% increase in the city’s property tax base, according to state data.

Chicago lost 10,000 students last school year, continuing a decade-long trend of shrinking enrollment. While nearly 70% of Chicago students are low-income, those numbers have also dipped as parts of the city have grown wealthier.

“They’re sitting on a lot of property wealth and they don’t necessarily tap that property wealth to the level they could,” Martire said of Chicago. He also noted that districts, including Chicago, are getting a windfall this year from a tax on corporate profits, which affects the formula but is not as reliable as a source of revenue.

The state legislature overhauled how it funds public schools in 2017 and promised to equitably fund the state’s 852 school districts by 2027. To get there, the formula prioritizes every district into four tiers. Tier 1 districts get the most help from the state to fund their schools and Tier 4 districts get the least. For the coming fiscal year, Chicago moved from Tier 1 to Tier 2, which effectively puts it further back in line for new money.

Jessica Handy, director of government affairs at Stand for Children, said she didn’t anticipate Chicago Public Schools would be recategorized this year because the district still serves a large population of students from low-income families.

Handy said the evidence-based funding formula is better than the system it replaced, but the state needs to increase its contribution to get all districts to adequate funding.

“Illinois was a deeply inequitable school funding system,” Handy said. “Evidence-based funding made it better because we’ve set up a framework to get ourselves to adequacy. But at a rate of $350 million per year, it’s not enough to fully fund the many needs of our school districts, especially our neediest school districts.”

Robin Steans, president of Advance Illinois, said the formula is designed to provide a base amount that districts can count on year after year. Any new evidence-based funding a district receives becomes part of its base funding in the future year.

“This predictability can be quite helpful to districts for planning purposes,” said Steans. “For many districts, including CPS, their base funding minimums have grown over the past five years as they have received new evidence-based funding.”

Nearly 60 school districts, including many surrounding Chicago, will get a larger share of the $350 million in new money after being reclassified due to enrollment shifts and property wealth adjustments.

Among them is Lincoln Way Community High School District 210, which saw a 131% increase in the number of students identified as English Language Learners. Similarly, Warren Township High School District 121 saw a 20% increase in students learning English.

Another district getting a larger share of the new state education money is Homewood Flossmoor District 233, which saw declining enrollment but also had a drop in property wealth, according to the formula.

Last year, an analysis released by a group of legislators, superintendents, and experts tasked with overseeing the new funding model estimated that it would take until 2042 to fully fund schools if the state continues to invest $350 million — considered the base amount.

Pritzker and the general assembly hoped that the more than $7 billion in emergency COVID federal funding the state received will make up for not being able to add more than $350 million toward the state funding formula.

State education advocates have warned that without an increase in state funding schools will be seeing a cut in services because districts base long-term staffing positions on state funding, not short-term federal funding.

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org. Becky Vevea is Chalkbeat Chicago’s Bureau Chief. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkeat.org.