Middle and high school students are used to answering questions at school. But they don’t often get asked how they view their teachers and classrooms.

Last month, Chicago Public Schools students got a chance to weigh in when they took a new 15-minute survey inviting them to rate statements such as: “In this class, my ideas are taken seriously.” “This teacher makes what we’re learning really interesting.”

The results of the Cultivate survey will land in principals’ inboxes next month — part of a new district effort to measure student attitudes toward school, which experts say can help boost students’ grades and well-being.

The survey stems from more than a decade of research at the University of Chicago into the ways classroom environments can shape how students feel about school and how well they do. It measures whether students believe their teachers are nurturing a sense of community and belonging, giving meaningful assignments and quality feedback, listening to students’ input, and more.

“What’s clear is that teachers have a lot of power over the learning conditions in their classrooms — and those learning conditions are really powerful,” said Camille Farrington, managing director at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, who helped develop the survey with partners at UChicago Impact.

The questionnaire for students in grades five through 12 could become a twice-a-year ritual. But at a time when the district is rethinking how it holds its campuses and educators accountable, officials stress they will not use the survey to evaluate teachers or rate schools.

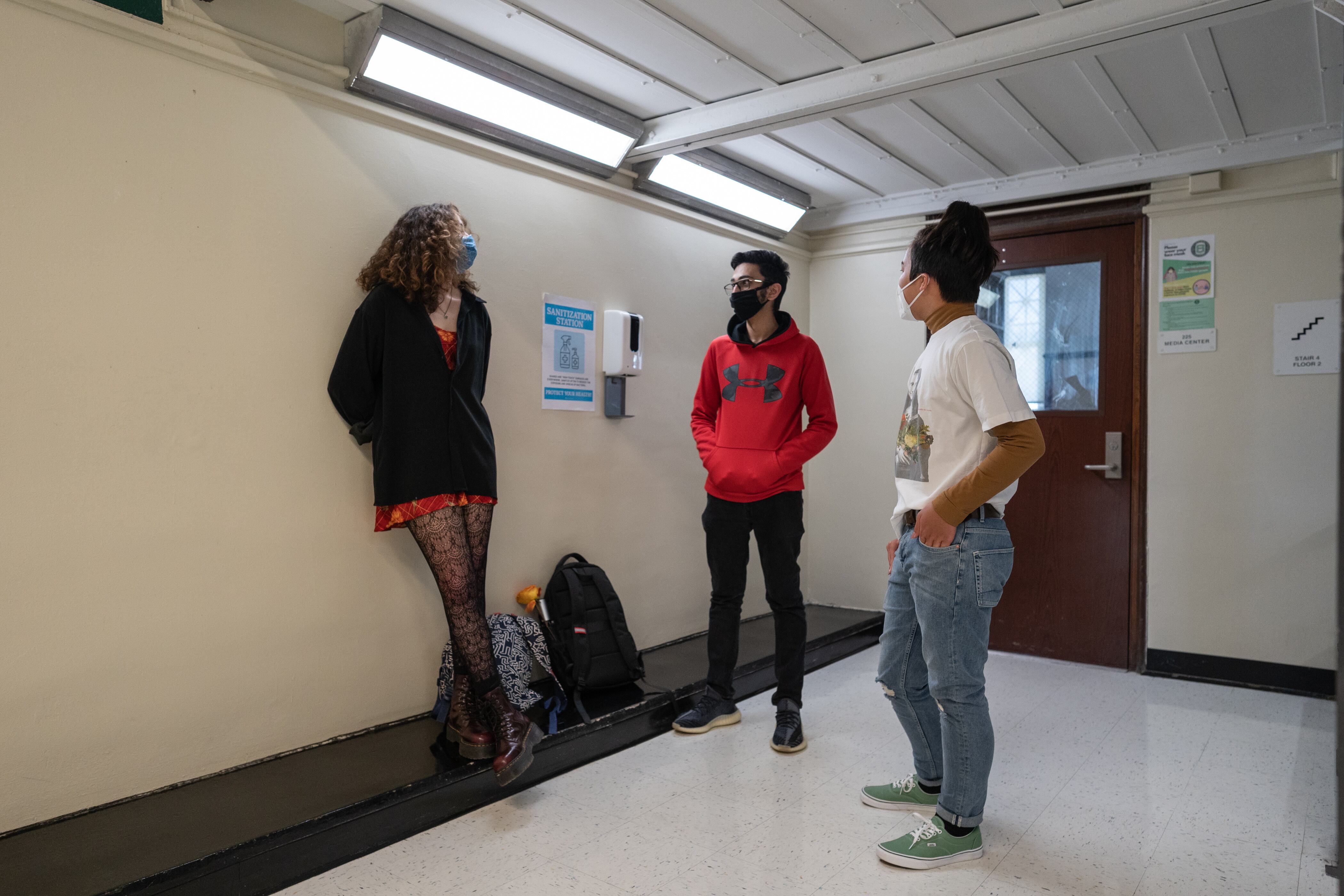

The pandemic’s disruption and the racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd have spurred unprecedented attention to student mental health and how it affects learning — and to the idea that giving students more agency on campus could be key to improving instruction. Districts across the country are stepping up efforts to understand students’ experiences and exploring ways to enlist students in making decisions. Chicago follows Minneapolis and some smaller districts and charter schools in adopting the Cultivate survey.

The Chicago Teachers Union has voiced support for the new survey, which its leaders feel can arm teachers with valuable information to improve their practice and help forge stronger bonds with students. But the union says the district rushed to implement the survey this past fall, and educators have not yet received professional development on making use of its findings.

Chicago adopts student survey after decade of development

In 2012, researchers at the University of Chicago began digging into how classroom environments can power or sabotage learning. They felt they could use their insights to create a tool for teachers and school leaders to get feedback from students.

They tested multiple versions of a questionnaire and by 2015, landed on a reliable way of measuring students’ perceptions of their learning conditions. But it was a lengthy, cumbersome survey meant for researchers. The university enlisted districts and charter schools to test a shorter version, and Farrington flew around the country to review the data with educators and fine-tune the survey.

“I didn’t want to unleash another survey on schools without being sure that the data would be meaningful and useful to teachers and school leaders,” she said.

Last school year, Minneapolis Public Schools became the first large district to adopt the new survey. Last fall, Chicago Public Schools signed a no-bid contract with the University of Chicago to implement the Cultivate survey as well. It’s meant to complement 5Essentials, another University of Chicago-developed survey that gauges school climate more broadly by asking staff, parents and others how they view school safety, leadership and more.

The district will pay the university up to $286,000 in the first year to provide and help administer the survey. The contract says the university will provide professional development for school staff, calculate scores for each school and help compare fall and spring scores. The university will also explore the possibility of breaking down data by race, poverty, disability, and English learner status.

A board resolution approving the contract said data would go into “interactive reports that are shared publicly and allow for schools and community members to track performance over time.” But the contract itself says the data will only be shared with school staff after district approval, and district officials now say the resolution is inaccurate and might need to be amended.

District leaders have said recently that becoming more attuned to student experiences is key to their push to improve learning. The district has given students a larger role on local school councils and encouraged schools to form student voice committees that give school leaders feedback on improving campus climate. More than 160 campuses, including some middle schools, now have such committees.

Last summer, the American Journal of Education published a study showing that Chicago Public Schools ninth graders who felt educators and administrators listened to their ideas and concerns got better grades and had higher attendance.

Chicago Public Schools officials said the survey is an important tool, and the district is embracing it at a critical time.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has deepened some of our most persistent, longstanding opportunity gaps,” a district spokesperson said in a statement. “To close these gaps, we need to think and act differently, and that begins with listening to our community members, especially our students.”

The district stressed that for now, it only has a one-year agreement with the university to administer the survey twice in 2022-23. It doesn’t yet have data on how many students in grades 5 through 12 who took the survey this winter.

How will student survey data be used?

Pavlyn Jankov, a Chicago Teachers Union researcher, said he and other union leaders met with the University of Chicago team that developed the survey. He said he was impressed by the research and thought that went into designing the questionnaire and the guidance schools will receive to help step up their student engagement.

Teachers are eager for that kind of feedback, he said, and the very act of soliciting it will help strengthen relationships with students.

But he said the union would have preferred to see the district pilot the survey in a smaller number of schools before embracing it districtwide. A relatively small group of staff participated in training on implementing the survey according to Jankov, but when results arrive at schools next month, the overwhelming majority of teachers will not have received professional development on how to use them.

In Jankov’s understanding, principals will receive the data and decide how broadly to share it with school communities and how to use it.

“We have disparate leadership styles across the district,” he said. “Principals will be the gatekeepers of how this information is rolled out in every school.”

Some might even take them into account as they review teachers’ overall performance, Jankov said.

But Farrington said the new Cultivate questionnaire was not designed to evaluate teachers or schools. In fact, its creators intentionally made it hard for any district to do so.

Principals will not get classroom-level data, but rather results for their schools as a whole as well as by subject and grade level. That will allow teams of educators to review data and act on it collaboratively.

Meanwhile, Chicago Public Schools is gearing up a new system for evaluating its campuses after it scrapped its controversial rating system amid the pandemic. The 5Essentials survey results factored into those former ratings. But the district has stressed it won’t use Cultivate results for accountability purposes.

The University of Chicago has also teamed up with colleagues at Stanford University, who developed a similar survey meant for use by educators who want to get real-time input from students on their own classroom practices. Farrington said Chicago Public Schools is exploring the possibility of making that survey available to teachers as well.

“The idea of having students just sit quietly in school just doesn’t pass muster any more,” she said.

Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify who will have access to data from the Cultivate survey.

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.