An hour before dismissal on a recent Friday afternoon, eight Brighton Park Elementary School students huddled in a classroom with Jennifer Moorhouse, a teacher who works with English language learners.

They were there for a voluntary, biweekly support group run by Moorhouse and Stephanie Carrillo, a school counselor, for students grappling with the upheaval of immigration and the adjustment to a new country, new city, and new school.

She asked the children — a mix of sixth through eighth graders who had recently arrived in Chicago as part of an influx of migrant families — to share the best and worst part of their week.

One boy said the best thing was that his family had moved to a new house. Another child looked up, her hair slightly covering her face. She shrugged her shoulders and struggled to come up with a worst moment.

That’s OK, Moorhouse said in Spanish, she doesn’t have to have a low point.

The girl then added, “No mejor,” meaning there was no high point either. After a moment of silence, the whole group burst into laughter.

These students, who arrived in Chicago between last year and this year, are among the more than 20,000 newly arrived migrants in Chicago since last August, with many fleeing from Central, South American and African countries experiencing political and economic turmoil, according to city officials.

Chicago Public Schools does not track immigration status and has not shared how many migrant students have enrolled in schools. But the district has pointed to clues of an increase, including 7,800 more English learners enrolled this school year, compared to an annual average increase of 3,000 such students.

As of mid-September, 2,250 migrant children were housed in the city’s shelters, according to records from the city’s Office of Emergency Management and Communications that were obtained by Chalkbeat.

Educators have raised concerns that many Chicago schools don’t have the resources, such as staff, to provide new migrants with the right language instruction, recently pleading with the state to send more help.

But there are also questions about whether newcomers have the social-emotional support they need at school. These students have potentially endured dangerous journeys to the United States, on top of the stress of leaving their homes behind for shelters or other temporary living arrangements in a foreign place.

That latter concern led Moorhouse to launch the support group at Brighton Park last year after she met a migrant student who was showing signs of trauma. The student, whom Moorhouse met in January, didn’t want to be in school and sometimes, the student’s body would shake uncontrollably, she said.

At one of the sessions Moorhouse held, the student shared a personal story about his journey to the United States. Afterward, Moorhouse recalled, the student said: “My chest isn’t hurting. I can breathe.” Moorhouse felt it was a sign of healing.

In some ways, Brighton Park is well-positioned to host this support group. As a community school, it partners with a nonprofit organization to provide wraparound services for its students. Carrillo, the school counselor who helps Moorhouse with the support group, works with the school on behalf of its partner nonprofit, Brighton Park Neighborhood Council. Brighton Park Elementary’s community schools funding also helped to pay for the training on the model that the support group is based on, according to Cecilia Mendoza, the school’s assistant principal.

The model is known as STRONG, or Supporting Transition Resilience of Newcomer Groups, which focuses on teaching children how to understand and cope with their stress before they’re invited to share more personal details about their journey to the United States, if they choose.

It’s unclear how many schools have specific support groups for migrant students like the one at Brighton Park. About $35 million of the district’s budget this year was allocated for social-emotional curriculum, behavioral health supports for students, and additional social workers and counselors, according to a district spokesperson.

This year, Moorhouse and Carrillo are starting with the basics.

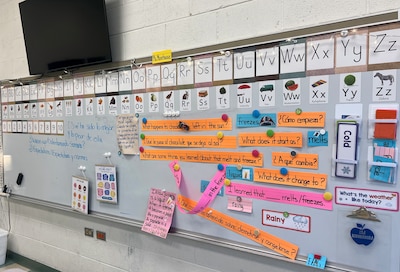

On that recent Friday afternoon, in the classroom where Moorhouse gathered with eight of her students, bright orange and blue strips of paper on the dry erase board described concepts of melting and freezing in English and Spanish: “Que le pasa al chocolate que se deja al sol?” (What happens to chocolate left in the sun?).

A plastic cupboard sat against the wall, filled with shoes, socks, and clothing donations Moorhouse had collected through her Amazon Wishlist. Sheets of paper taped to the wall have words of affirmation in both languages: “Tus emociones son validas.” (Your feelings are valid.)

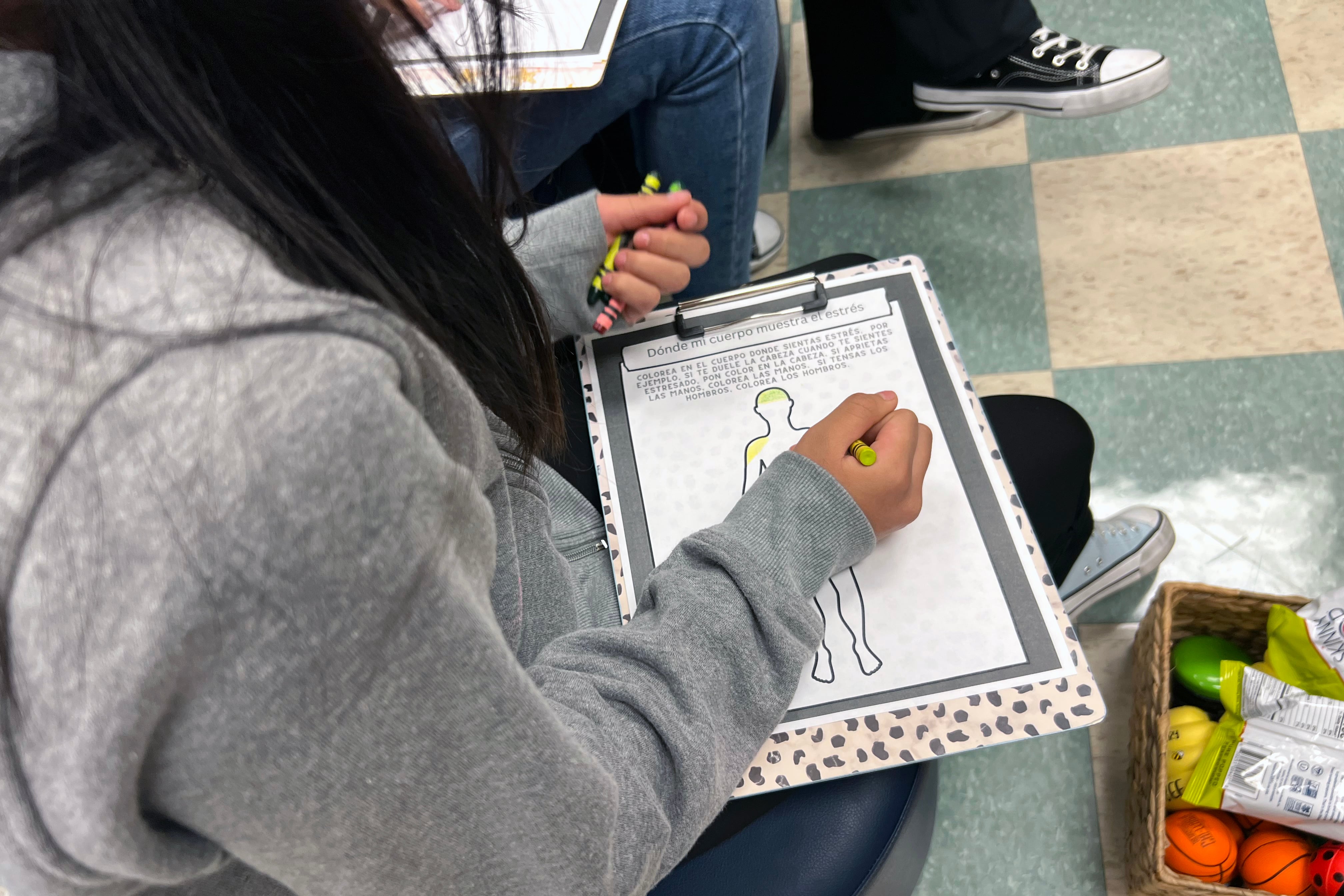

After their icebreaker, Moorhouse passed around crayons and a worksheet with the outline of a human body. She explained that stress can cause physical pain and asked her students to color in the part of their bodies that hurt when they are stressed.

“Entonces para mi, cuando yo estoy estresado, mi estómago me duele,” she told the students, explaining that her stomach hurts when she’s stressed.

One girl, wearing a pair of sneakers donated through the Amazon wishlist, used a green crayon to fill in the top of the head. She colored the shoulders with a green-yellow.

When Moorhouse asked students to share, one boy said stress gives him a headache, and then he feels like throwing up. A low “hmm” spread through the group, as if others recognized the boy’s feeling.

At 2:35 p.m., about halfway through the session, the students received a new worksheet. This one had a large triangle on it, and each point represented something different: pensamientos, sentimientos, y acciones. Thoughts, emotions, and actions. Moorhouse wanted the students to reflect on how a thought may lead to a feeling, which ultimately leads to an action.

After a couple minutes jotting down their thoughts, the students shared their responses. One boy smiled as he described an example: When he’s talking to other students and they suddenly begin speaking in English, he feels as if he’s been removed from the conversation.

“How does that make you feel?” Moorhouse asked him in Spanish.

“Bad,” he replied.

“What’s your action?” Moorhouse responded.

“I walk away,” he said.

That day, Mendoza, the assistant principal, was peeking in.

“I don’t think students or people in general sometimes realize the effect that has on others who only speak one language,” Mendoza said later. “So that really stuck with me, and I thought about how we could have that conversation, perhaps, with the students … because they might not be aware that they’re doing that.”

Moorhouse then presented a challenge for the students: How can they change their thinking about a situation, in order to elicit better action? One boy gave the example of taking a hard math test that he doesn’t know the answers to, so instead, he asks to go to the bathroom.

He was stumped when Moorhouse asked him to think of a better action. She opened the floor to the group, but no one came up with an answer good enough for Moorhouse. When she pressed them to think harder, they hit on a solution: He could ask the teacher for help — for understanding the exam, or perhaps even asking to take it another day.

With about 15 minutes left, Moorhouse and Carillo passed around stress balls shaped like bee hives. They asked the students to squeeze hard and pretend that they were squeezing out the juice.

A couple of kids laughed as they squeezed their fists and then released pressure.

Around 2:55 p.m. Moorhouse handed out a blank calendar worksheet. For the following week, students would be expected to log how they’ve practiced relaxation strategies, such as grabbing an ice pack from the nurse or using a stress ball, when feeling stressed. One student shared that drawing helps.

It was time for dismissal. The students didn’t run out the door. They stayed back to chat with each other. A few grabbed extra bags of Skinny Pop.

As the weeks go on, Moorhouse and Carrillo will meet individually with each student to assess whether they want to talk more about their personal experiences of coming to the U.S. and what would be appropriate to share with the other students.

In those conversations, students may show signs of needing more individual counseling provided by the school, such as bursting into tears while recounting a story, Carrillo said.

Some students take a while to open up, so it’s unclear how much they’ll participate going forward, Moorhouse said. One of those quieter students is the child who had shared that there was no highlight or lowlight of her week. During the hourlong session, this student gradually opened up a little more.

And when most of the other children left at the end of the day, that student stayed behind. She wanted to talk some more one-on-one with Moorhouse.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.