Every school day at 10:30 a.m., two dozen middle schoolers shuffle into a classroom at Warren Elementary on Chicago’s far south side. One by one, they boot up a Chromebook at their desks.

Fourteen miles north, another nine students log in from their classroom at STEM Magnet Academy just west of downtown.

They are all taking the same course: Middle School Algebra with Raluca Borbath, who teaches virtually.

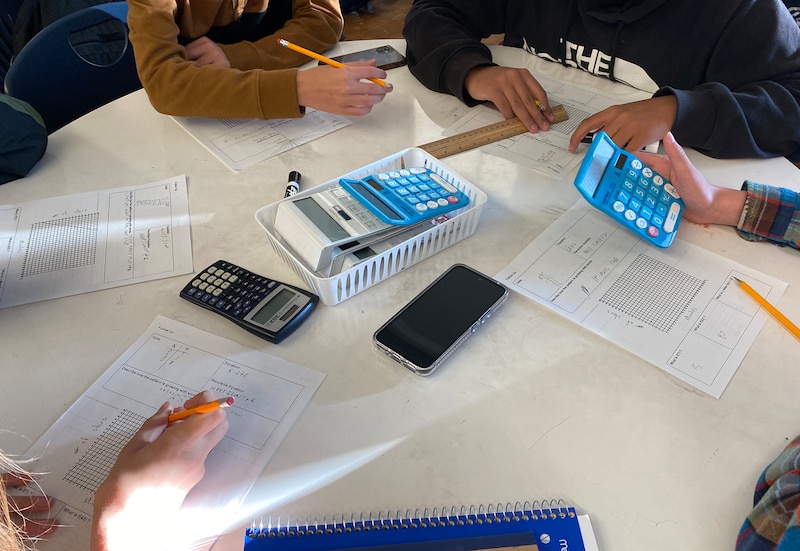

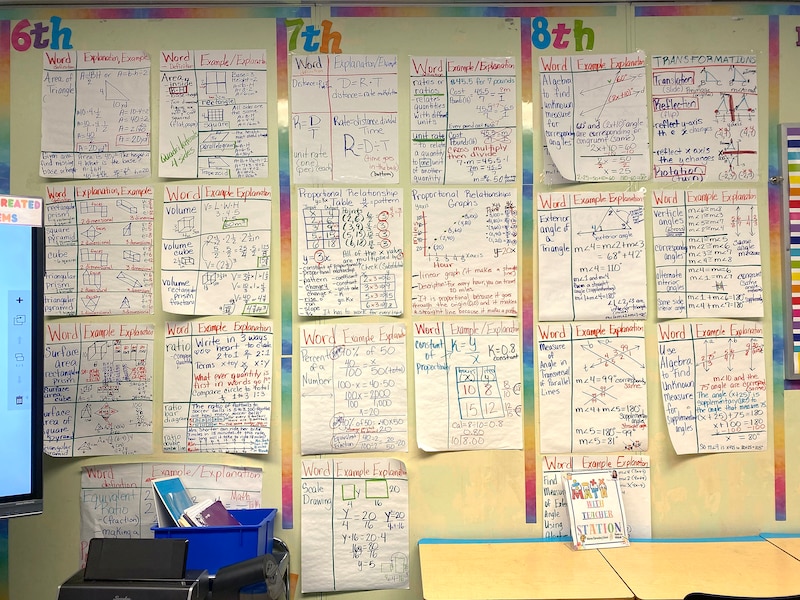

On a recent November morning, Borbath shared her screen to begin Lesson 13: Introduction to Two-Variable Inequalities. The students, who log in through Google Meet, dove into a problem about making bracelets with two different kinds of beads — one kind cost $1 and the other cost $2.

The class spent the next hour solving and graphing: 2x+y ≥ 10.

Classes like Borbath’s, in which middle school students learn algebra partly online, have been critical to Chicago Public Schools’ efforts to reduce long-standing inequities in access to the course, which is seen as a gateway to better high schools, better colleges, and ultimately, better careers.

Put simply: Mastering algebra in middle school can give kids an advantage for the rest of their educational trajectory. But in Chicago, access to the course before high school has long been inequitable.

Schools without algebra in the middle grades have been largely located in predominantly Black and lower income neighborhoods on the south and west sides. For students who do take algebra in eighth grade, state data shows white and Asian American students in Chicago Public Schools are more than twice as likely to pass than Black and Latino students.

But the district says it is trying to address the inequity and has found some success.

In addition to the Virtual Academy, which was created during the COVID-19 pandemic and has offered middle school algebra for the past two years, the district also partners with three local universities to get more middle school teachers certified to teach the course.

Data obtained by Chalkbeat shows:

- Over the last decade, the number of CPS elementary and middle schools offering algebra grew from 209 to 366.

- The number of middle grade teachers with algebra credentials increased in the past two years from 428 to 489.

- A decade ago, roughly 10% of the city’s eighth graders took the district’s Algebra Exit Exam. Last May, nearly 25% did.

- There are still 85 district-run schools and 35 charters where no students took the Algebra Exit Exam last year.

Other cities have tried expanding middle school algebra with varying success. In New York City, then-Mayor Bill de Blasio promised in 2015 to get algebra in every middle school and saw rates of students taking and passing the course go up. But that district’s focus has shifted back to improving freshmen algebra. Similarly, the state of California recently considered recommending all eighth graders take algebra, but decided to leave the decision to local school districts.

Corey Morrison, director of mathematics at Chicago Public Schools, said the district is focused on equity, not a one-size-fits-all approach.

“It’s algebra choice for all,” Morrison said. “We want to get to a place where every eighth grader has a choice and can choose – as much as an eighth grader can without their parents making them.”

Algebra skills ‘build from the bottom up’

Algebra has long been a core requirement for high school freshmen in Chicago and the rest of the country. But for decades, it’s also been offered to advanced middle school students. Those who took it early would be on a fast track to taking calculus senior year, giving them a leg up on college applications and a strong foundation once enrolled in university.

“If you’re spending three years on your mandatory classes, you only have one more year to look for AP classes, or dual credit classes, or anything else that you want to do,” said Borbath, the teacher of the hybrid class. By taking algebra early, students are able to free up their high school schedules.

But in Chicago, data shows stark disparities in who has historically had access to algebra in middle school. Chalkbeat Chicago obtained and analyzed the number of students who took and passed the district’s Algebra Exit Exam. The two-hour test, taken at the end of each school year, consists of 34 multiple choice questions and six short answer problems. Students who pass can move on to geometry.

Ten years ago, roughly 200 of the district’s 500-plus schools serving middle schoolers had students who took the exam. Now, more than 350 do.

At Warren, no students took the district’s Algebra Exit Exam in 2018, data shows.

The small school sits in the heart of Chicago’s Pill Hill neighborhood, a South Side enclave once home to many doctors and pharmacists who lived in the spacious homes down the street from the nearby hospital. It serves 271 students; 99% are Black and 80% come from low-income families.

STEM Magnet Academy, which shares a section of Borbath’s algebra class with Warren, is in the city’s more affluent West Loop and serves 403 students; 38% are Black, 34% are Asian American, 18% are Latino, and 6% are white. About 43% come from low-income families. In 2018, 14 students at STEM Magnet took the Algebra Exit Exam and 7 passed. But no students have taken it since then.

Borbath also teaches a morning section of algebra to middle school students at three other predominantly Black south and west side schools — Daley, Sumner, and Brown — all of which had no students taking the Algebra Exit Exam as recently as 2019, according to data obtained by Chalkbeat.

Morrison said the pandemic was terrible in a lot of ways, but the way the district is using the Virtual Academy to close gaps in access to algebra is a “silver lining.”

At Brentano Elementary in Logan Square, no students were taking the Algebra Exit Exam in 2018, district data show. Seth Lavin became principal nine years ago and said adding the course took time and planning.

“The wrong way to do this is just to change your eighth grade course and say, ‘Now we do algebra,’” Lavin said. “The right way to do it is to build from the bottom up so that the kids can be ready for it.”

Lavin said Brentano teachers led the effort to rework how math was taught in order to offer the course.

“This required, for us, changing what sixth graders were doing, and then changing what seventh graders were doing before, eventually, we could change what eighth graders were doing,” Lavin said.

Now, all eighth graders take algebra in school, Lavin said. And starting last year, Brentano started offering a before-school algebra course to any interested seventh grader.

Lavin said he’s able to pay one of Brentano’s teachers to teach the early morning algebra using federal COVID recovery money. Once that money runs out, the offering could be at risk.

Staffing middle school algebra can be a complicated equation

There are logistical and budget hurdles to overcome in order to offer algebra to middle schoolers, Lavin said.

“A teacher in your building has to have an algebra certification, or a high school math endorsement,” he said. “That requires some groundwork.”

Chicago Public Schools launched an effort 20 years ago, known as the Chicago Algebra Initiative, to boost the number of middle school students taking algebra. In partnership with three local universities, the school board pays tuition for up to 90 middle school teachers to earn a credential to teach algebra each year.

Morrison, with the district, said the goal is to eventually have at least one certified teacher in every school, but the math hasn’t always worked out.

“How do you pull a handful of kids out to give them a robust algebra course when there’s only one eighth grade teacher?” Morrison said.

For the past couple of years, the Virtual Academy has been able to step in to serve those schools.

Last school year, 777 middle schoolers across 120 schools took the virtual course and this school year, the number climbed to 1,140 middle school students across 142 schools, according to the district. Roughly 300 take the class during the school day and 800 take it before or after school.

Morrison said the virtual courses are also showing teachers and administrators that offering in-person algebra is possible.

“It changes the mindset of teachers and administrators,” he said. “There are enough students in your school, in your community, where we can work towards putting an in-person course in your building, because that’s the ultimate goal.”

District data obtained by Chalkbeat shows that 489 teachers working at 287 schools have an active credential to teach algebra to middle school students. That’s up slightly from 2020 when 428 teachers at 248 schools had them. A district spokesperson said data on algebra credentials was not available prior to 2020.

Warren is hoping to offer in-person algebra next school year. Veteran teacher Tracey Kidd is working toward getting credentialed through the University of Chicago as part of the Chicago Algebra Initiative. Last school year, she was the teacher in the room where middle schoolers logged into virtual algebra.

“It’s kind of hard to do (algebra) virtually sometimes, because kids, they wander off a little,” she said. “But if you’re in the room with them, then they’re gonna focus more, and they get that one on one attention from you.”

Kidd currently teaches intermediate math and knows many students are ready to handle the rigor of algebra.

Younger students get a jump start in algebra

In Sandra Shorter’s classroom at Warren, a group of sixth grade students are starting pre-algebra with the goal of taking algebra next school year as seventh graders.

“We’re doing ratios, unit rates, and then we’re gonna graph them and write them as equations,” Shorter explained.

Morrison, with the district, said algebra is not just for certain students who want to be scientists or engineers. It teaches important skills such as problem-solving and critical thinking.

“Math is for everybody. But do you need to get on the accelerated track in eighth grade? Not necessarily,” Morrison said. “Do you still need to learn algebra? Yes.”

Algebra is a graduation requirement in CPS, but the stakes for taking it before high school can feel high.

Last week, 13- and 14-year-olds across Chicago found out their scores on the district’s High School Admissions Test — a one-hour exam that partly determines whether they can go to the city’s top high schools. Though the content of the test is not public, many parents and students say taking algebra in middle school gives students a leg up.

“It will help us with a test to get into high school,” said Brentano student Liam Dolik. “That is something that’s so huge in eighth graders’ life, especially in Chicago. It’s not the best but we have to do it so we might as well prepare for it.”

Dolik is one of nearly 30 seventh graders who come to school at 7:45 a.m. every weekday to take algebra. They spread out across nine tables as the morning sun streams through the towering windows in classroom 306.

Lavin said all seventh graders were offered the option to take algebra before school, and about half of them decided to do it. But Lavin wrestles with whether the morning section for seventh graders is creating a new inequity.

“Sometimes there’s this temptation to go ahead instead of going deeper,” Lavin said. “At the same time, our kids are in the CPS reality where everybody’s trying to figure out how to get as high a score as they can in the high school admissions test.”

At the end of the day, Brentano is still a neighborhood public school in a diverse neighborhood, offering advanced math to everybody, Lavin said. “That’s increasing equity in the district.”

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.