Last spring, as Chicago schools were grappling with how to recover from the pandemic, district CEO Pedro Martinez urged campuses to go big and bold on summer school without worrying about the price tag.

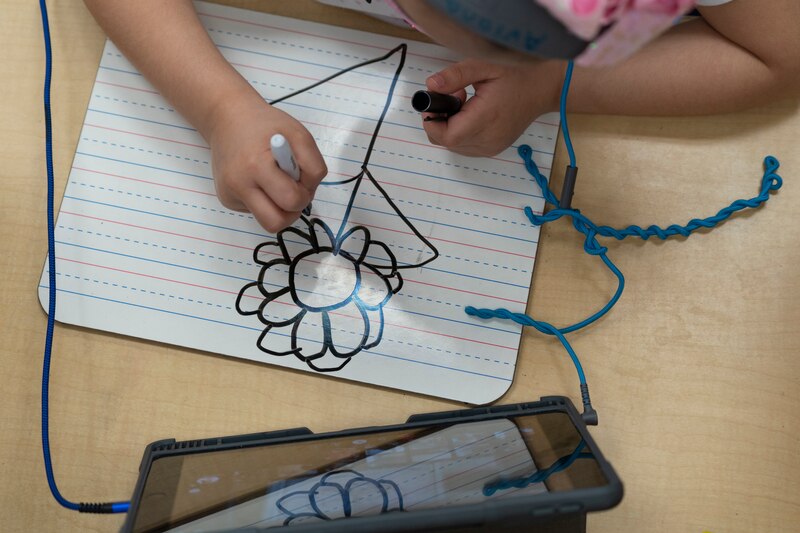

Tiffany Tillman, the principal at Melody Elementary on Chicago’s West Side, grabbed a notepad and started dreaming up a “summer university” for her predominantly low-income Black students. There would be “campuses” focused on academic recovery, sports, arts, and more.

She paid her entire staff of roughly 40 to work that summer, complete with counselors, psychologist, and social worker. She wanted a safe place for her students that blended learning and fun — breakfast and taco bars, field trips, a book club, a DJ on the last day.

In Chicago, as in other districts, the pandemic and an influx in federal relief dollars made summer school a much bigger deal — a key strategy for helping students bounce back from COVID’s toll. In 2022, the district went all in, spending 50% more than the previous summer: an unprecedented almost $40 million.

Data Chalkbeat obtained this month shows 73,000 students, or a fifth of the district’s overall enrollment, signed up, many for multiple programs.

A record 42,500 students enrolled in enrichment, or Out of School Time, programs designed by school leaders, sometimes in partnership with local nonprofits. But almost all other programs — including ones that help students catch up academically or make the transition to kindergarten and high school — were significantly underenrolled.

And even as the cost and the stakes for students have risen, the district has struggled to track student signups and attendance. That makes it harder to determine if the summer school push paid off — a key question as the district rushes to direct resources to vulnerable students and tighter budgets loom.

Chicago Public Schools took more than six months to fulfill a Chalkbeat records request for school-level enrollment data. For some campus-based programs, the numbers showed repeat signups or unusually high enrollments, raising questions about accuracy. No attendance numbers are available.

The district, which is gearing up to release information on summer school offerings for 2023, said it launched a new effort last year to better track summer participation; that effort will continue this year.

“We continue to strengthen our data collection and reporting methods to best serve our K-12 students in summer 2023 and beyond,” the district said in a statement.

Meanwhile, principals such as Tillman at Melody say the influx of summer resources made a difference for students.

Tillman said one student from a nearby school who was required to attend an academic recovery program at Melody told her: “I wish I could have been here the whole school year. Then I wouldn’t have been in summer school.”

Tracking summer participation remains a challenge

In a decentralized system where some programs are district-run, some draw students from multiple campuses, and some are school-run, tracking summer numbers has long been a challenge — and until recently, a low priority. In fact, not that long ago, schools kept their own records and didn’t report them to the district.

With three systems for entering enrollment data currently, it takes work to distinguish between the number of enrollments and that of unique students, who can enroll in more than one program in the course of a summer. Some principals told Chalkbeat they were required to report attendance data for some programs in the district’s Aspen system this past summer, but district officials said sharing reliable numbers would require entering the dates when programs at all district schools were in session — a labor-intensive undertaking.

But COVID made summer school a higher priority, upping the stakes for capturing data.

Last spring, district CEO Martinez had told the school board he felt an “obligation” to offer students engaging programming both after school and during the summer. He wanted campuses to go all-out in designing summer enrichment programs tailored to their own school communities.

“We have shared with schools that funding is not a limit when it comes to summer programs,” he said at the time.

District officials circled back with the school board in July to tout a summer of blockbuster enrollment. They announced preliminary numbers showing almost 91,000 students had enrolled, clearing a 90,000 target the district had set and far outpacing the district’s enrollment numbers for the previous summer. The 2022 total touted in July included about 33,000 recent Chicago Public Schools graduates contacted through an “alumni supports” program – text, email, and phone nudges to follow through on enrolling in college – but who did not attend district summer programs.

In the summer of 2021, the district now says, 55,000 students signed up for summer programs, a number that does not appear to include “alumni supports,” based on data the district provided that year. It is not clear whether that number included “alumni supports.”

Enrichment programs schools created in-house — some focused on STEM, arts, and sports, and some offered in tandem with local nonprofits — were a particular success, district officials said. Enrollment for the district’s extended school year program for students with disabilities, programs that prepare children for preschool and kindergarten, and a string of new career and technical education camps came in well below targets.

Chalkbeat wanted to see what these numbers looked like at the school level and submitted a Freedom of Information Act request for the data last July. After a series of delays, the district provided data in December only for Summer Bridge, a program for students in grades 3, 6, and 8 who do not meet the criteria to pass on to the next grade, and Summer Acceleration, for struggling eighth graders. That data accounted for only about 6,500 students out of 91,000 the district had said signed up for summer school.

When Chalkbeat requested attendance data tracked in the district’s Aspen system, officials responded that the district does not collect that information “centrally or comprehensively.” Schools have traditionally seen a gap between signups for summer programs and actual turnout, and the pandemic dampened attendance year-round.

The district also said it does not centrally maintain numbers for students who complete summer programs, which can mean different things for different programs and campuses. The district did share completion numbers with Chalkbeat in the fall of 2020, showing that 14,200 out of 21,600 students who enrolled in largely virtual programs that summer stuck around until the programs’ end.

Officials said the district is working to improve how it centrally tracks summer data to ensure that its greater investment is resulting in equitable access across the city. But the challenge is doing that in a way that doesn’t overburden schools with data entry, allowing them to focus on providing strong programs, they said.

The enrollment data provided to Chalkbeat this month, which doesn’t include the alumni outreach program, shows that many of the 73,000 students who signed up for summer school did so for more than one program. The data shows 115,000 enrollments. Many students signed up for the same program at the same school more than once. That could be because some programs held multiple sessions, but some students enrolled repeatedly in programs they seem unlikely to take twice, such as an orientation program for incoming freshmen, raising questions about the data.

More traditional programs remained underenrolled throughout the summer, but numbers for school-designed enrichment programs, known as Out of School Time programs, grew significantly between that July presentation and the end of the summer. Data shows the average program drawing roughly a quarter of a school’s enrollment. On some campuses, enrollment for these programs appeared unusually high, with the number of students signed up in line with or even exceeding a schools’ overall enrollments.

“Schools were encouraged to use Out of School Time to support return to school for Fall,” the district said in a statement. “We were intentional in wanting to keep the momentum going from the first full year back from the pandemic.”

District officials said feedback from schools was positive

At Melody Elementary, which serves about 300 students, 190 showed up for summer programs, including some from other area schools attending Summer Bridge. Attendance data is not available from the district, but Tillman says she observed strong turnout throughout the summer.

The district has not compared outcomes for students who attended summer schools and peers who did not. But Tillman credits the summer push with a start-of-the-school-year engagement boost and with what she described as higher-than-expected mid-year academic progress.

At the July school board meeting, school board member Elizabeth Todd-Breland said she had also heard high praise from principals. Some were “raving” about the influx of funds at back-to-school bashes last summer.

Martinez said one school leader on the district’s principal advisory council told him, “I was in tears because I saw the resources and I could set up the programming that I wanted to set up.”

Some principals told Chalkbeat drawing students to summer programs remained a challenge, and staffing issues lingered after a trying school year that made teachers more reluctant to take on summer work. One elementary principal said summer programs there drew an “astonishingly small number of students,” though the enrichment program the school offered did better than centrally managed programs such as Summer Bridge.

“CPS told schools that all families could opt in pretty late,” he said. “As a result, a lot of spots sat empty.”

A couple of principals told Chalkbeat that their schools ultimately opted not to host their own programs. “We were just so tired, and it was going to be a short summer,” one said.

Patrick Brosnan of the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council said in the summer of 2022 the nonprofit served almost 1,000 students in programs in partnership with five elementary and two high schools in the neighborhood, including enrichment, arts, sports and field trips and the transition program for high school freshmen.

Interest was up from the previous summer when the nonprofit offered some hybrid programming, Brosnan said, but participation still remained below pre-pandemic levels — perhaps in part a reflection of pandemic-era enrollment losses in some schools.

Susan Stanton of the nonprofit ACT Now!, a coalition of community-based organizations that provide summer and after-school programs, said many of its members partner with Chicago Public Schools to offer programs it fully or partially funds. These programs picked up somewhat over 2021, when COVID still cast a long shadow, she said.

But, she said, the first two summers of the pandemic took a lasting toll on programs, which rely on word-of-mouth and younger siblings of former participants to draw signups. She felt principals did not get enough guidance on how to set up their own programs and the district should have leaned on community-based organizations more and earlier.

“Principals were essentially handed money last minute,” she said, “and building these partnerships doesn’t just happen with the snap of your fingers.”

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.