Sitting on the floor of a South Side police station and reading “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?” by Eric Carle to two young Venezuelan refugees, Chicago teacher Melissa Faccini Deming suddenly seized on an idea.

She looked at the 5- and 7-year-old girls and launched into a Colombian folk song that asks the sun to “warm me up a little.” “Sol solecito, caliéntame un poquito,” sang Deming.

The children immediately joined in, along with their mother Maria and a chorus of other newly arrived migrants crowded into the lobby of the 22nd precinct police station in the Morgan Park neighborhood. Chalkbeat is not using their real names to protect their privacy as they seek asylum.

It was a brief moment of joy and familiarity for the mostly Venezuelan asylum seekers and refugees temporarily housed at police stations until the city finds more permanent housing.

More than 10,000 refugees and asylum seekers have arrived in Chicago since August, about half of them still staying in temporary shelters, police stations, and respite centers.

When Deming, a Chicago Public Schools elementary school teacher, heard about refugees placed in her neighborhood, she felt she had to reach out and offer them something special — familiarity. She made arepas and offered the traditional South American stuffed cornmeal patties as a taste of home.

Deming then realized she had something else to offer. On her next visit she brought books to read to the children. The kids loved it. This inspired her and a few local teachers to hold regular classes for the refugee children at the community garden across the street from the police station.

With the youngest learners, Deming danced and sang and read books, while retired teacher Laura Amaro read lesson books in Spanish with an older child at a picnic table.

Amaro said she hoped to allow the kids to feel a sense of normalcy and to help prepare them for new schools in the fall.

With migrants arriving regularly in Chicago on buses sent by Texas governor Greg Abbott, local officials do not know how many school-age children are among the refugees and asylum seekers, nor how many will enroll in Chicago Public Schools in the fall.

Many of these children have been out of school for months, have endured traumatic experiences, are not proficient in English, and live in unstable and under-resourced conditions.

The children, their adopted communities, and their teachers will cope with these together when the school year begins.

But volunteers and teachers like Deming and Amaro are spending their own time this summer to help them feel welcome.

While schools and the city have some systems to support English language learners, educators who work with refugees note that both students and teachers who work with them need more specialized support.

Refugee trauma is ‘very specific’

Maria and her two daughters endured a frightening and treacherous journey from their home in Caracas, Venezuela, to Chicago. They traveled on foot through seven countries, she said, begging for food in the streets and witnessing people drown in mud in the forests. She saw a woman die with her baby still in her arms.

“I saw horrible things in that forest,” Maria said. “I would not wish that forest on my worst enemy.”

Bilingual Chicago educators Sol Camano and Josh Lerner have seen trauma from these kinds of experiences manifest in different ways in schoolchildren.

For example, a student of Camano’s who had been separated from her mother for three years, struggled with transitions throughout the school day. One of Lerner’s students had difficulty forming relationships with peers and teachers.

“These children are coming from a lot of trauma, and the first thing cannot be academics,” said Camano. “It has to be, how can we help them work through this trauma … making sure there are bilingual therapists and teachers to be there with the child before you start to think about their math and literacy scores.”

The school district has invested more than $30 million in social and emotional learning and mental health resources, and last school year increased the number of social workers and counselors in schools, a district spokesperson said in a statement.

Still, Camano sought out her own training and researched trauma-informed education to better help her students.

“I think it’s very important for there to be more trainings for teachers or more information for teachers on how to help students that have this much trauma. And this is a very specific trauma,” she said.

She herself spoke only Spanish when she started school in 2000. Her parents had come to the U.S. from Argentina.

“I remember sitting on the sidelines as other children played and communicated with the teachers,” Camano said. “I could only say ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘please,’ ‘thank you.’”

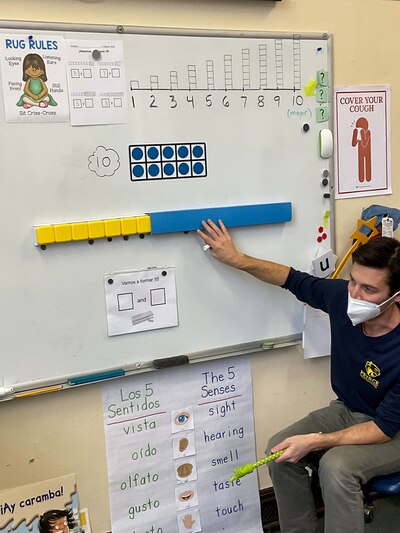

Now, two decades later, she is a dual-language pre-K teacher at Dr. Jorge Prieto Math and Science Academy in the Belmont Cragin neighborhood, where she teaches Spanish-speaking kids from all over Latin America.

In her classroom Camano prioritizes making her students feel welcome by helping them maintain their native languages and by including in her lessons books, food, decorations and music from their cultures.

“What I would have wanted so much as a child is to have gone to school and people speak to me in my language and invite me and welcome me, and be able to talk to the other students,” Camano said. “I didn’t really have that, so I make a big point to give that to my students as much as possible.”

At least a decade of research demonstrates better outcomes for English learners when their native language is used in the classroom.

For language learners who are also refugees “it’s [about] much more than language,” Camano said.

It all comes down to trust, according to Jeanine Ntihirageza, a Northeastern Illinois University professor of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages.

“You can make [learning] engaging, you can make it fun, but deep down if they don’t feel safe, they can’t learn,” said Ntihirageza, who also is founding director of the Genocide and Human Rights Research in Africa and the Diaspora Center. “Once the children feel kind of safe, then the world is open … but this comes with stability.”

Stability and safety can be hard to come by.

Back at the police station in Morgan Park, a few weeks into the classes, a bus arrived unannounced one day to take the kids and their families to shelters around the city. One child cried as she boarded the bus and said goodbye to Deming.

Two weeks later, more refugees arrived at the station, only one child among them — a precocious 4-year-old. Deming reconfigured her classes in the garden to offer English lessons to the now primarily adult group.

“It’s a very fluid project so far, which has been good, because it’s a very fluid situation so far,” she said.

Teachers offer refugees more than language

For recent arrivals, education challenges start long before entering a classroom.

Federal law gives refugees and other youth experiencing housing instability the right to immediately enroll in public schools even when they do not have records. Chicago Public Schools offers transportation, school supplies, and food assistance.

However, misinformation, unreliable internet connections, and lack of stability can still impede enrollment.

Deming says she has spoken with families who thought they were not eligible to enroll and others who believed that they could enroll only in a school two hours away.

When Maria was referred to a school for her daughters before summer break began in early June, she said it was too far to easily get there, and when one of her daughters got sick, she put it off. Now, she’s looking ahead to August.

According to a statement from the district, officials intend to share more information about accommodating more English learners later this summer.

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s administration told the Chicago Sun-Times they may open an enrollment center for new arrivals at Roberto Clemente Community Academy High School and potentially in other locations before school starts on Aug. 21.

Many of the recent arrivals who’ll join CPS will qualify for bilingual education. While the district reported that it has 2,255 bilingual educators, it has a vacancy rate of 2.5% for bilingual positions, according to a district spokesperson.

Last fall, “there were not enough bilingual certified staff, especially in the middle grades,” said Lerner, who teaches English learners at Peirce Elementary School in Edgewater. He is an English language program teacher and collaborates with administration and other teachers to optimize education for English learners at Pierce.

The teacher union contract recently increased the number of such positions and added incentives for bilingual certification.

Lerner thinks the district should remove barriers to school volunteering — like a long online form, fingerprinting, and hard-to-access information — to enable parents who are refugees or speak other languages to help in the classroom, provide bilingual help, and strengthen home-school ties.

“I have seen, firsthand, mothers who when I show them the online form they kind of reverse course and say no,” he said.

“My hope is that [my daughters] develop well and don’t get frustrated,” Maria said. “The most important thing is that they feel good and like going to their classes. From there, I’ll just hope everything goes well.”

Deming checks in with Maria and her daughters by phone and occasionally visits or has them over at her house. She hopes this will help them feel welcome in Chicago and in schools. Still, she worries.

“How many people will understand them and where they’re coming from?” said Deming, who is training to be a leader teacher through with CPS’s Personalized Learning Department to provide students with more personalized education that focuses their strengths and interests. “The more we can help them feel like there’s a desire to understand who they are first … that’s where connections can be forged.”

A previous version of this story said that Deming teaches preschool at Chicago Public Schools. She is an elementary school teacher.

Crystal Paul is a freelance reporter covering communities, arts, race and culture. Contact Crystal at crystal.l.paul@gmail.com or @cplhouse.