Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and statewide education policy.

Demetrius Hobson’s voice piped through the loudspeaker into every classroom at Matthew Henson Elementary School on Chicago’s West Side.

It was just before 3:45 p.m. on June 19, 2013. In a few minutes, the bell would ring to dismiss classes on the last day of the school year at Chicago Public Schools.

Hobson had arrived the previous year, fresh out of Harvard’s principal leadership program, with endless energy and new ideas. He had been ready to transform the 250-student school that served mostly Black students from low income families in North Lawndale and was “gearing up for the long run.”

Now, he had to do something no principal wants to do.

“Good afternoon, Matthew Henson Elementary School, and congratulations,” Hobson intoned. “This is our final few minutes as a school.”

That day would mark the largest mass closure of public schools in the nation’s history, as Henson and 49 other Chicago schools shut their doors for good. Some 17,000 students and 1,500 staff would scatter to schools across the city. Many others would leave the district altogether.

The promise made at the time by then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel was that the students would go to better schools, and the district would save money by offloading expensive-to-maintain aging buildings.

“I know this is incredibly difficult, but I firmly believe the most important thing we can do as a city is provide the next generation with a brighter future,” he said in a statement after the school board voted on the closures. “I am confident that … our children will succeed.”

The moment capped months of raucous public hearings, days-long marches, downtown protests, and even arrests of activists who demanded Emanuel and his hand-picked school board reverse course.

On that June day, as Hobson and others said good-bye to their schools, questions hung in the air: What would happen to neighborhoods being disrupted? Would buildings get new life or fall into disrepair? Would Emanuel’s promise of better futures for students come to fruition?

Henson security guard Kelvyn Cockrell was not as confident as the mayor.

“I just hope and pray that somehow this works,” he said, standing outside the school’s main office on the last day of school.

Nearby, Mia Bonds, then a soft-spoken eighth grader and the valedictorian of her class, helped a teacher pack up a box.

She would be moving on from Henson anyway, heading to Whitney Young High School, one of the district’s top test-in high schools. But for her brother, then a second grader, the closure would mean being reassigned to Hughes Elementary a few blocks west.

“I don’t think it’s fair,” Bonds said at the time. “I want people to remember that Henson was not just a school — it was like a family.”

Before the bell rang at Henson for the last time, Hobson searched for words of comfort as he spoke to the students over the intercom:

“I want you to remember that education is the key to unlock the golden door to freedom,” he told them. “And I want you to know that every day at Matthew Henson Elementary School, education is liberation.”

A principal and his students ‘find community somewhere else’

About a week after the last day of classes, Hobson says he got a phone call from a district official telling him the school was about to be officially mothballed.

“Get to the school, get your things,” Hobson recalled the official saying. “We need to lock the doors and turn in your keys.”

Henson was one of 46 buildings that would be emptied out. Desks, chairs, books, bulletin boards, and everything else would be moved out — taken to other schools, warehoused, sold, or simply thrown away.

Chicago Public Schools would pay an Ohio-based logistics company to manage all the stuff from the shuttered buildings — a contract that would eventually double from $8.9 million to $18.9 million. Years later, metal desks, solid wood chairs, and other relics from the school closings would end up for sale on Craigslist.

The three-story, mint green and tan brick building once called Henson would be put up for sale the following year.

After his school closed, Hobson needed a break. At the time, he didn’t want to walk into another school building and start over again. He told his wife, ‘If I go back into another school, it’s going to be a school I start.’”

But near the end of that summer, Hobson said, Chicago Public Schools called again: Would he mind stepping in as interim principal at another school?

He was still on district payroll, so he took the job in Woodlawn. But midyear, Hobson was asked to go to Earle Elementary in Englewood, a school that had been designated as a welcoming school for Goodlow Elementary, another closed school.

In some of the buildings that welcomed displaced students in the fall of 2013, the transition was tough and sometimes even chaotic.

“They took two low-performing schools and put them together,” said Darlene O’Banner, a grandmother of four children at Goodlow and later Earle. “They were setting us up for failure.”

The shuffling of students was a monumental task for the district. Officials spent millions of dollars on additional staff, new iPads, and building repairs at roughly 50 schools designated to welcoming students from closed buildings. But instead, some of the students scattered. Just over three-quarters of students attended the welcoming schools that were designated to take them in. The rest fanned out to 200 other schools across the city, WBEZ reported at the time.

Hobson’s time at Earle turned out to be brief: He had gotten a job offer to open a new school. In San Francisco.

So Hobson and his wife packed up and moved West, where he would become the founding principal of a new public middle school named after that city’s first Black mayor, Willie L. Brown.

Many of those impacted by the closures also moved away. Data obtained by Chalkbeat showed that roughly a third of the students who attended closed schools transferred out of CPS. Some families and advocates said the loss of an anchor institution, like a school, would lead to more displacement and disinvestment in the segregated Black neighborhoods, not less.

Bonds started freshman year at Whitney Young, one of the city’s top high schools that accept students based on their test scores and where they live. It was far more diverse and less segregated than Henson, which served mostly Black children from low-income families. The year Bonds enrolled, the student body at Whitney Young was 30% white, 24% Black, 27% Latino, and 15% Asian American.

“I feel like I needed to be in a more diverse type of schooling,” she said. “I saw Whitney as an escape. So I was there early, leaving late.”

Her brother enrolled in third grade at Hughes, the school where Henson students were assigned. It was closer to their apartment, Bonds said, but they “just liked Henson better.”

“Once you close schools down like that, people have to find that community somewhere else and adapt,” she added. “In this situation we were forced to, it wasn’t like a choice.”

Vacant school buildings and new starts in and outside Chicago

By 2017, Henson’s building still sat vacant. The windows were boarded up. Litter blew across the cracked blacktop. The marquee outside the front door was blank, no longer emblazoned with the school’s name.

The district had managed to sell only a handful of the shuttered schools — most on the north side — to luxury housing developers or private schools. They repurposed a few as district offices or transferred them to other city agencies and put the remaining 30 out to bid for a second time.

In May 2018, the Board of Education had an interested buyer for Henson’s property, which sits across six parcels. The Single Room Housing Assistance Corporation offered $55,000 and put forward a plan to convert the school into 80 mini-studio apartments for low-income people, including veterans, single mothers, and people with disabilities.

There were a lot of similar proposals — and dreams — for the vacant buildings left behind in the wake of the historic closings. A “teacher’s village” with a mix of housing and retail. A women’s center and artist incubator. A community center for formerly incarcerated people. Affordable housing for seniors.

Hobson, in the meantime, was trying to bring a new school to life nearly 2,000 miles away.

He was “working day and night” to recruit students for a new STEM middle school in San Francisco, hiring staff, applying for grants, and designing curriculum with the district leadership.

But in late 2018, Hobson returned home to Chicago once the school opened. He remembers thinking: “‘Maybe I should just start over? Go back to the classroom. See what that feels like.”

Bonds, who had graduated from Whitney Young in 2017, became the first in her immediate family to go to college.

“A lot of people urged me to go. They said I needed to leave the west side of Chicago,” she said. “Every college I applied to I got accepted.”

She chose Northern Illinois University. “Nearby, but far enough away.”

Her brother finished elementary school at Hughes and enrolled at a Noble charter high school.

Data obtained by Chalkbeat show 59 percent of second graders from closed schools, like Bonds’ brother, are still enrolled across the district. It’s one of the cohorts of closed school kids who remained enrolled at slightly higher rates than comparison schools that were also on a list of 129 schools being considered for closure in 2012-13, but were ultimately spared.

But the closures had thrown other students off course.

A 2018 study by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research found that students impacted by the closures had academic outcomes that were “neutral at best, and negative in some instances.” For example, students from closed schools initially had lower reading and math scores. Reading scores recovered, but the gap in math scores persisted.

The school district had promised a five-year moratorium on school closings after 2013. When it ended in 2018, CPS closed four high schools in Englewood. But in exchange, it built a new state-of-the-art STEM high school.

Still, Chicagoans questioned if the district would return to an annual cycle of closing a handful of schools every year, as it did prior to the 50 closures.

How school closings were decided remains ‘hurtful’

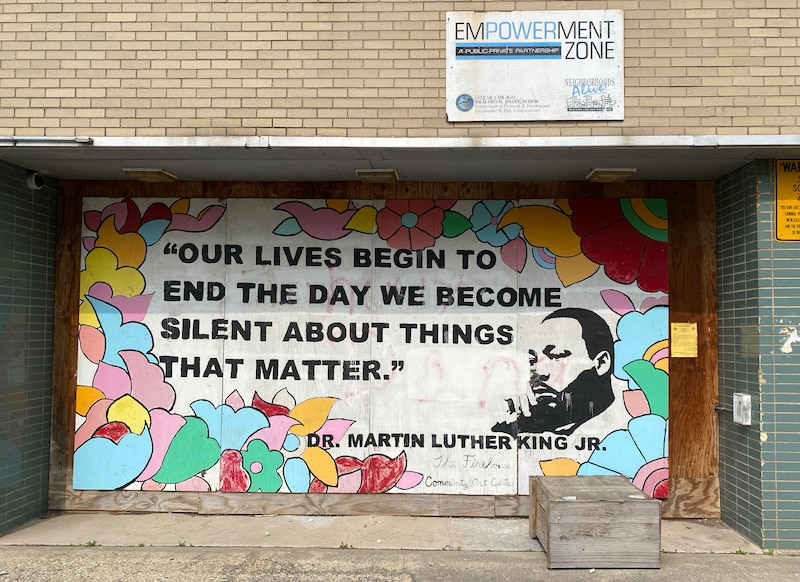

On a hot June day this year, exactly 10 years and three days since the last day of school in 2013, the entrance to Henson was still blocked by boards on which someone had painted a mural.

It read: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

A City of Chicago Empowerment Zone sign, with Mayor Richard M. Daley’s name on it, hung above the mural. A weathered and crumpled piece of yellow paper from the Department of Water Management was stapled to the side, asking the owner to contact them within 10 days so workers could access the water meter and avoid a shutoff.

Chicago Public Schools still owns the building. There have been no micro-studios for veterans, single mothers, or disabled people.

The sale approved by the school board to the Single Room Housing Assistance Corporation never went through. Former alderman Michael Scott Jr. held it in the City Council’s Committee on Housing five years ago.

The blacktop where an inflatable bounce house stood on the last day of school was cracked and faded. Near a side entrance, a few men in their thirties were sitting on buckets, smoking. One swept broken glass off the ground and into a garbage can.

Hobson has driven by Henson’s building a few times. One time before the pandemic, he remembers turning the corner to see Henson’s green and tan building.

“I was surprised to see how disheveled the building, the environment was,” Hobson said. “You could see vestiges of night parties, you know, bottles, and food bags, and everything just kind of collected on the stairs.”

The story is the same for many vacant schools. Approvals have stalled and some projects have languished as they wait for financing.

Hobson is back in the classroom now, teaching middle school social studies at an elementary school on the West Side closer to downtown than Henson was. It’s also named William Brown STEM Elementary, but after a different William Brown than the school he started in San Francisco.

It’s harder to know where the 252 students who were at Henson are today. One Henson student featured in a WBEZ/Chicago Sun-Times series said after fourth grade when the closure happened, he went to three different elementary schools and three different high schools in Chicago and the suburbs before getting his high school diploma at an alternative school.

Data provided by the district did not break down outcomes by school.

But data obtained separately by Chalkbeat Chicago shows that about 60 percent of Henson’s kindergarten through second grade students — those still likely to be enrolled — were at district schools during the 2022-23 school year.

Of all the students who attended schools that closed in 2013, fewer graduated and more dropped out when compared to the rest of the district. But these outcomes were similar to schools that were also on the chopping block in 2013, raising questions about whether the closures resulted in a better education for students.

Hobson said he still occasionally thinks about what it would’ve been like to “be a fly on the wall” in the rooms where the school closings decisions were made.

“Now that we can see on the other side, based on the data, there was no real transformation for the children,” Hobson said.

“What we were told and what actually happened are two different realities.”

As for Bonds, she moved back home to North Lawndale this summer after finishing her master’s degree at NIU. Her family is still in the same apartment about six blocks from Henson. She’s working for After School Matters this summer, as she has for the past several years. And next year, she’s doing City Year, an Americorps program that stations full-time mentors in high-need schools.

Looking back now, Bonds said the historic mass school closings weren’t “the end of the world.” People adapted. But it still felt like “a numbers game” that made communities like hers feel “powerless to a system.”

“It wasn’t like it was super detrimental,” Bonds said. “It was just hurtful.”

Her little brother is now entering his senior year at the same Noble campus he started at and is on track to graduate, she said.

Most Chicago students enrolled today have not experienced their public schools closing down for good. The kindergarten students of 2013 are set to graduate in 2025 — the same year state legislators have given the city’s school board permission to close schools again.

Mila Koumpilova and Samantha Smylie contributed reporting.

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.