Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and statewide education policy.

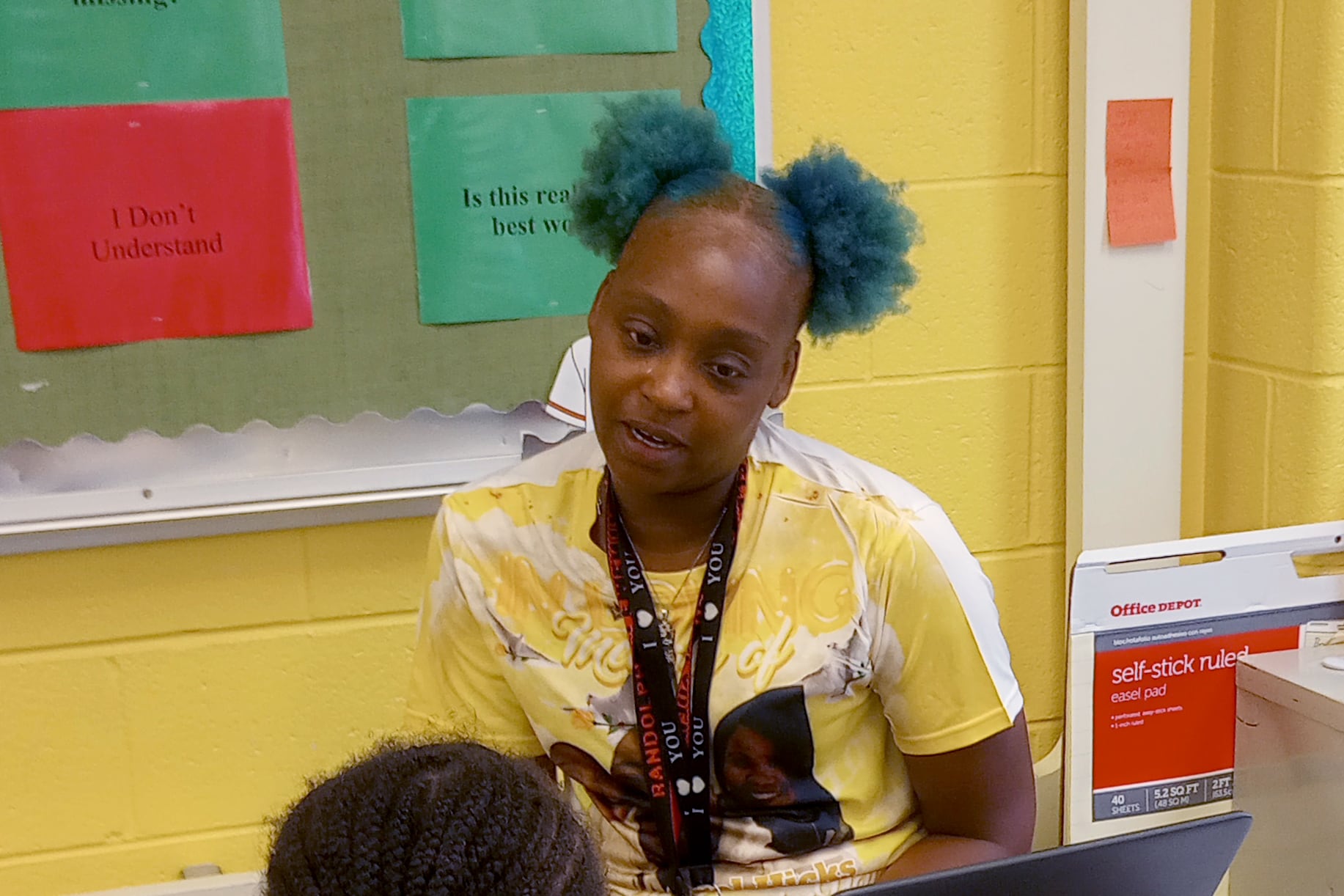

A. Philip Randolph Elementary School parent Victoria Wicks has hair as vibrant as her personality. Last week it was colored a bright teal, but she changes it up frequently — sometimes picking a color requested by the students she tutors.

The mother of eight, with children ranging in age from 10 months to 16 and including twins, is deeply involved at Randolph in Chicago’s Auburn Gresham neighborhood on the South Side. Six of Wicks’ children currently attend the school and she’s on two parent councils.

On a recent Friday, Wicks sat across the table from a student and gave instructions in a practiced, serious tone. This exercise would assess what level of tutoring the girl would be placed into for the rest of the school year.

Once the reading of passages and sight words was over, Wicks let her nature shine to the fullest, telling a student, “Good job! That’s what I’m talking about!”

Wicks became a tutor during summer 2021, when a fellow parent invited her to join Randolph’s contingent of the Chicago Public Schools Tutor Corps. The district had earmarked $25 million in federal pandemic relief money to hire and train 850 tutors to help kids catch up on much-needed early reading and middle- to high-school math skills.

Wicks took on the job of reading tutor with her trademark enthusiasm, rehearsing how to teach the lessons and give assessments, using the curriculum provided. She found success helping her tutoring groups read better.

But across the district, the corps got off to a slow start. Only 450 tutors were hired by halfway through the 2021-22 school year. Onboarding was slow and it took a few months to get the curriculum providers — Amplify for reading, Saga Education for math — under contract and training tutors.

Since then, the number of tutors has grown. On the first day of school, CPS had more than 600 tutors, about three-quarters of the initial hiring goal of 850. Currently, tutors are working in 229 schools, but the district declined a request to provide a list of the schools and their locations.

A summer hiring push helped schools, including Randolph, staff up, some principals said. But this school year marks the final year the district will have federal COVID relief funds to spend on tutors before the dollars run dry next fall.

Chicago’s tutoring is high-quality but small scale

According to district officials, Tutor Corps has reached 10,000 students with at least one tutoring session since its 2021 launch. Like many districts nationwide, Chicago’s program aimed to provide students “high-dosage” tutoring, which means students meet in a group of no more than four with the same tutor over an extended period of time, like a semester or a full school year. The intensive sessions are 30 minutes during the school day, at least three times a week.

The tutors must be trained to use a structured curriculum that can meet students where they are and offer lots of chances to practice the skills they are learning. Research shows this kind of tutoring benefits struggling students the most.

Meeting these exacting requirements can be tough. Other districts have struggled to make it work, but Chicago has stayed true to it from the beginning.

At Randolph, tutors meet with no more than three students up to five times a week. Principal Keviyona Smith-Ray also makes sure tutors have time to meet with the teachers of the students they are tutoring.

“CPS is doing something we’re not really seeing across the United States,” said Maryellen Leneghan, vice president of district partnerships for Saga Education, which provides training and curriculum for the math tutors.

She said Chicago’s uniqueness is threefold: The district has chosen to keep tutoring fully in person, maintain control of tutor hiring, and balance strict adherence to the model with flexibility for schools.

“The number of students it has been able to help has been impressive,” said Becky Betts, chief marketing and external affairs officer for A Better Chicago, which has financially supported tutor hiring.

But 10,000 students is barely a drop in the bucket for a district of more than 300,000 students, said Natasha Dunn, a CPS parent and Black Community Collaborative co-founder.

Though data on the tutor corps’ effects has yet to be made public, a study from the University of Chicago’s Education Lab is expected later this school year.

While kids learn, schools develop teacher talent

Like many tutors, Wicks had the same students all year last year and got to know them well, even attending a parent-teacher conference for one of them to show how much the child had progressed over the year.

As a parent herself, she has seen some of her own children grow as readers through tutoring, and she uses what she’s learning as a tutor to help them at home.

“Being with Tutor Corps helps them understand how to break down the words,” she said. ”When it’s time for them to go into that classroom and read, they’ll use the strategies we have taught them.”

Smith-Ray said the tutors are also building relationships with students beyond their academic sessions and helping them open up about tough issues in their lives.

She’s also seen an unexpected perk: Two of last year’s tutors have joined the permanent staff — one as a special education classroom assistant and the other as an office assistant.

“It’s an amazing opportunity to hire within the community,” said Smith-Ray. “The students want to be with them. They’re familiar with them.”

Across town, at Haugan Elementary in Chicago’s Albany Park, co-principal Heather Yutzy said Tutor Corps is becoming a “stepping stone” into teaching or other permanent jobs. At Haugan, one of last year’s tutors has moved into student teaching. That tutor’s younger sister, a recent graduate of Northeastern Illinois University, is now tutoring and planning a career change to go into teaching.

Northeastern is among a group of local colleges, led by Roosevelt University, that is creating a tutor-to-teacher pipeline. A Better Chicago awarded $1.6 million to Roosevelt University to build a tutoring pathway in partnership with other local higher ed institutions. According to A Better Chicago, about 65 Roosevelt students completed a full year of tutoring last year. Of them, seven Roosevelt students are moving into student teaching this year and another 10 students are expected to move into student teaching in fall 2024.

Getting sold on the program and finding the money

Though hard data on Tutor Corps’ effectiveness is not yet publicly available, tutors and principals can see early signs of progress on the ground.

Haugan parent Rita Tello joined the corps in the middle of last year as a math tutor. She has worked hard to help struggling middle schoolers see math as both challenging and fun.

Her groups broke into two-on-two teams to take Kahoot quizzes and play Jeopardy-style math games, often with a small prize for the winners.

Though not every student’s math grade improved, she could see growth based on their “exit slips” — a quick, weekly progress check — and a difference in their attitude toward math.

She said her students were skeptical of her and reluctant to do math at the start. But by the end of the year, she said, they were eager to come to tutoring. They would ask her, “Are you picking us up today? Are you picking us up tomorrow, Ms. Tello?”

At Randolph, Smith-Ray said one of the most obvious signs of improvement in math is that children know their multiplication facts fluently and no longer need a times table reference with them in classroom small groups.

She said the youngest students are the most likely to outgrow the need for tutoring quickly, because many of the entering kindergartners had little preschool experience with pre-reading skills to learn sounds and letters.

Smith-Ray added that tutoring has also helped identify students who need individualized education programs, or IEPs, for special education services and provided “clear data” to help case managers and teachers “make sure students were given what they needed.”

However, for most students, Smith-Ray said continued tutoring will be key, “[They] are meeting their growth targets. They’re just still not at grade level yet.”

Not all students see linear progress. Barbara Formoso Minarik is the grandmother of alumni of James Monroe Elementary in Logan Square and has been part of the Tutor Corps since it started. Over the past three school years, she has seen children bounce in and out of tutoring.

Formoso Minarik wonders if some of her students need more support than tutoring can offer, like a referral for special education services. But that’s not a quick fix. “It’s just a long process,” she said.

It’s also a long process for a school district to embed and sustain a program like Tutor Corps. It can take about five years, said Leneghan, with Saga Education.

“Every year you learn more and more and build your capacity,” she said.

Chicago, like districts nationwide, doesn’t have much more time. The federal deadline to spend COVID recovery money is next September.

In a statement, the district said it “values this program and is exploring ways to continue providing these foundational services even after all federal [COVID]dollars are expended by September 2024.”

Whatever district officials decide, the principals at Randolph and Haugan want tutors like Wicks and Tello to continue their work.

“If I had to use my budget, I would still keep Tutor Corps,” said Smith-Ray. “It may not be six people, maybe it’ll be four, but I would still employ them.”

Yutzy, the Haugan co-principal, is just as determined.

“I’m totally sold on this program,” she said. “I think it has been a 100% valuable experience.”

Maureen Kelleher is a freelance journalist and longtime education writer. For Chalkbeat, she has previously written First Person pieces about choosing a new school for her daughter and helping migrant students enroll in school. Kelleher is now the editorial director at Future Ed, an independent, solution-oriented think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.