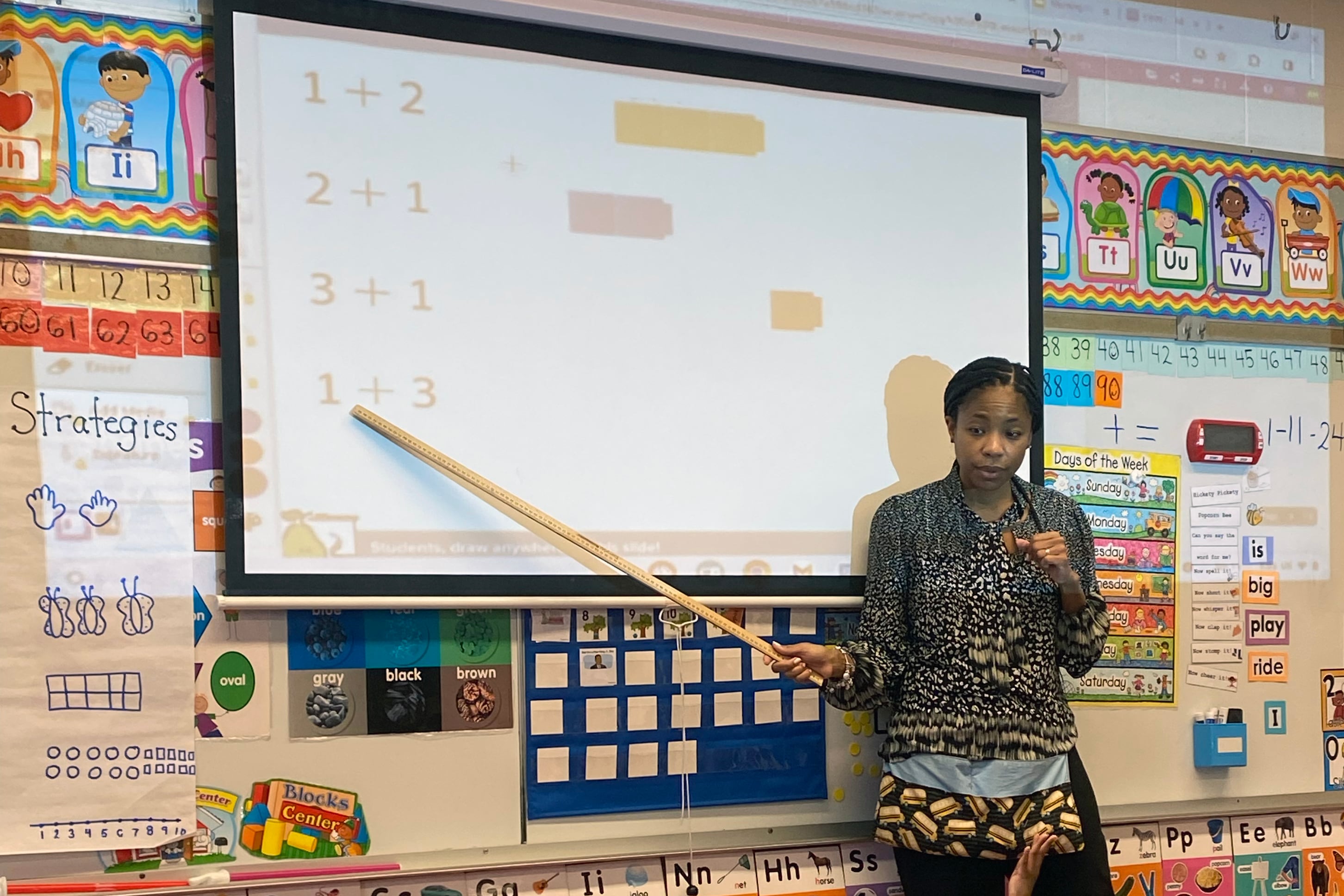

Arika Henderson’s kindergarten class at LEARN South Chicago campus usually starts the day with a math lesson. On this early morning in January, the kindergartners are working through addition problems.

Henderson, an 18-year veteran teacher, asks a student to help model to the class how to solve 1+2. Together, they use brightly colored blocks to represent the numbers in the equation and count out loud together.

Henderson then pairs off the kindergartners to solve more problems on their own — a strategy she uses to see if students are grasping the concept and provide additional guidance to those who need a little more help.

As schools across the country grapple with low math scores that have dropped over the last decade and plummeted even further during the COVID-19 pandemic, educators like Henderson are searching for ways to engage students and build proficiency in math.

In Chicago, some schools have brought in math coaches to help teachers hone their instruction, while other educators are turning to a concept called “productive struggle,” where students are encouraged to find their own strategy to solve math problems before a teacher steps in to give them a solution.

Finding ways to help young learners build a solid foundation for math learning is key to students’ success in later grades, experts say.

Math concepts build over time, so instilling those basic math skills is critical, said Susan Levine, a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago.

“Evidence shows that the level of math that you go into kindergarten with is predictive of your long term-trajectory,” said Levine. “It doesn’t mean students can’t catch up, but research shows that it is better to start early.”

Students who skip pre-K or K may miss early math skills

In kindergarten, students learn how to count to 100, add, subtract, and identify shapes — building blocks for more advanced skills such as multiplication, division, order of operations, and the Pythagorean theorem.

In Illinois, state law does not require parents to put children in school until the age of 6. It is unclear how many young children do not attend preschool or kindergarten, since the state only tracks the number of children in publicly funded programs.

But research has found that students enrolled in kindergarten, especially full-day programs, have significant gains in reading, math, and social emotional skills. Young children who don’t attend school before first grade may fall behind in being introduced to foundational math.

Enrollment in the early grades also took the biggest hit during the pandemic as parents were concerned about safety and virtual learning.

That may have further stalled progress in math for many young children.

The Illinois State Board of Education’s KIDS exam is an assessment given to students in the fall that measures the readiness of children entering kindergarten. Teachers are asked to assess students’ readiness in math, social-emotional skills, and language and literacy development. In Chicago, teachers found that 31% of kindergarten students were ready for math during the 2020-21 school year, down by 3 percentage points from 2019.

When Illinois shuttered schools in 2020 in response to the pandemic, Henderson’s kindergarten class that year was in its second semester. During virtual learning, she said, only 14 students showed up consistently on the computer.

“It was only so much you could control from your end,” Henderson said.

Now, those students are third and fourth graders. Henderson suspects many did not have a good kindergarten experience to build their foundational knowledge in math, she said. “I just feel so bad.”

At Ruggles Elementary located on the city’s South Side in Chatham, Shekinah Curry, a second grade math teacher who has only been in the classroom for three years, said she’s noticed gaps in students’ foundational skills when it comes to writing numbers and counting.

“You may have students who are still writing numbers backwards. There was one student, she put 97 when it was supposed to be 79,” said Curry. “I have students who may not know how to count by fives or students who are questioning ‘if I’m counting by 10s correctly.’”

Schools turn to math coaches, shifting strategies

As districts work to close the learning gaps, educators are shifting to different strategies, such as productive struggle, and schools are scrambling for ways to help teachers become more effective in teaching math. In CPS, the district has started to roll out the Skyline curriculum, which encourages students to be active participants in class.

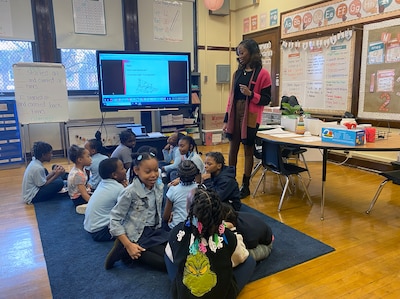

Katie Gleason, a first grade teacher at LEARN South Chicago campus, learned about productive struggle during her monthly meetings with teachers who are a part of the charter school network’s math professional learning community.

The approach — which Henderson used in her classroom and involves allowing students to work out ways to solve problems on their own after the teacher has first modeled a strategy — is effective because it requires students to make a connections between math concepts they are learning in class, Gleason said. However, the approach can be difficult for teachers to adapt to because some were taught to stand in front of the class and show students how to get the right answer.

“The math professional learning community has really taught us to allow students to have that productive struggle to try it on their own first and to teach them that it’s okay to make mistakes,” said Gleason. “We actually learn a lot through our mistakes.”

Some Chicago schools are also investing in math coaches — who observe educators in class to provide them with feedback and instruction strategies — to help bridge the gap in student learning and get students engaged in math.

At LEARN, math coach Midm Yi, who was a teacher for 11 years working with third, fourth, and fifth grade students, understands how difficult it can be for classroom teachers to catch students up to their current grade level while teaching new material.

In his role as a math coach, Yi spends his time observing teachers from anywhere between 25 to 45 minutes to evaluate engagement strategies teachers are using. Then he provides debriefing notes to teachers and resources they can use to improve their instruction. At the end of each week, he meets with other coaches in the network to go over training plans, professional development plans for teachers, and other projects.

Yi said he not only wants to see how teachers are working to fill in holes in students’ foundational skills, but also how they are “delivering that high, rigorous content that the curriculum is also providing for us. Are you intentionally using your plan time to effectively carve out specific time where you will be addressing those needs?”

In CPS, Corey Morrison, director of mathematics at the district, said his department has a math specialist for each grade who looks at research to see what math strategies are useful and a program manager who analyzes real-time data to see what interventions students need.

A CPS spokesperson said the district also has 198 coaches who support teachers in literacy and math. In addition, the district has also given funding to every school to hire at least one academic interventionist to work with students.

CPS’s Skyline curriculum, which is still being rolled out across the district, has also been a main force in changing how students learn math, Morrison said. Lessons are designed to encourage students to try their own math strategies in class, while teachers help students facilitate the conversation.

“It allows students to form their understanding based on what they’re naturally bringing to the classroom,” said Morrison. “Then, the onus is on the teacher to facilitate them to a point of deep understanding.”

School officials see promising growth

With the new support for educators and students the district added last year, Morrison said, schools are starting to see growth on students’ test scores.

“Last year was our first real year back from COVID,” said Morrison. “We saw a lot of promise from the strategies we put in place, and I think more of the intentionality around building positive math identity.”

Chicago Public Schools assesses students in reading and math between kindergarten and second grade three times a year on the i-Ready exam. At the beginning of the 2022-23 school year, 12% of K-2 students were at grade level at the beginning of the year. That number jumped to 50% by the end of the school year, according to data Chalkbeat Chicago received from a Freedom of Information Act request.

LEARN charter school network found that teachers who received math coaching or were a part of the network’s professional learning council during the 2022-23 school year saw their students score a higher proficiency rate on the NWEA and Illinois Assessment of Readiness exams, compared to teachers who were not receiving coaching. The charter school network — which serves 4,200 students across 11 schools in Chicago, northern suburbs, and Washington D.C. — went from one math coach last coach to five this year, according to a spokesperson. Three are shared between schools in Chicago and North Chicago; the schools in Waukegan, Illinois and Washington D.C. have one school-based coach each.

Teachers at LEARN like Katie Gleason have found math coaching and being a part of the professional learning community helpful. While Arika Henderson doesn’t receive math coaching, she is practicing productive struggle in her classroom.

Since the pandemic has eased, Henderson says she has seen growth in her students — some of whom had never been in school before — this year.

“They are getting in a routine of things,” she said. “The lightbulb has kind of come on and I can see the difference.”

On the cold January day in Henderson’s classroom, after she modeled a way to solve addition problems, her students worked on their own in their textbooks for about 10 minutes, tackling equations such as 2+1, 2+2, and 2+3.

Most students sat at tables named after flowers — sunflowers, tulips, lilies, roses, chrysanthemums — and worked with cubes. Others were asked to sit with Henderson’s instructional aide to get more hands-on support. Henderson walked around the classroom, keeping students on task and offering support where needed.

Some needed time to solve the problems, while others already found the answers. One student told Henderson: “I don’t need the counters. I already know it.”

A few minutes later, Henderson asked the class to share their answers and how they solved the problem.

Nearly every hand shot up, as the kindergartners jumped with excitement to tell their teacher and classmates what they had learned.

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education, and the state board of education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.