Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

When Jorge Alaves looks around room 110 at Lindblom Math and Science Academy each Wednesday morning, he sees 36 versions of his teenage self: Latino boys with a lot of potential at a high school full of high-achieving students trying to figure out how to be successful after graduation.

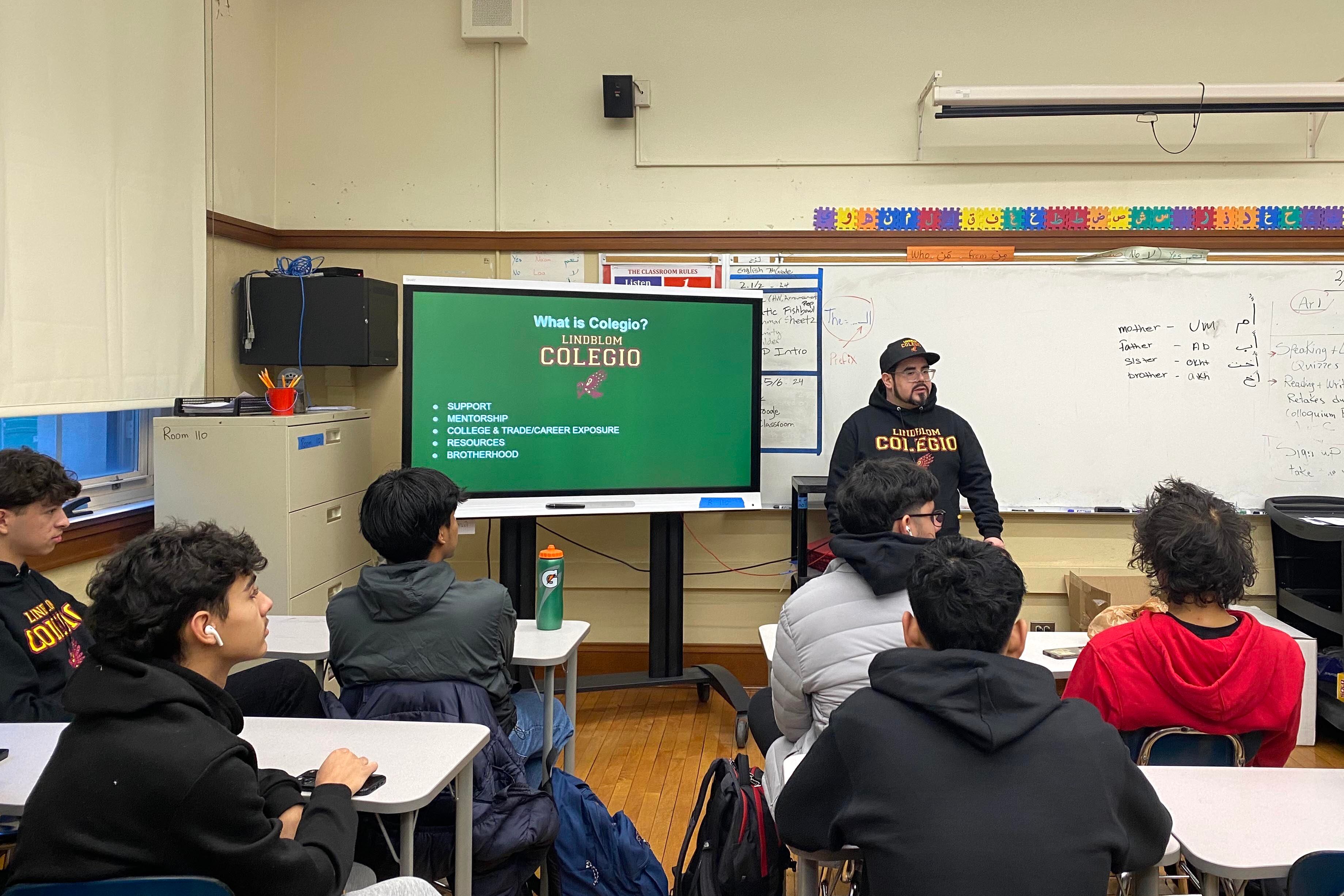

This is what’s known as “Lindblom Colegio,” a peer mentoring and postsecondary planning group for Latino boys that meets during the school’s colloquium days.

Alaves, one of Lindblom’s five counselors, launched the group about six years ago after noticing that Latino boys at the selective enrollment high school were less likely to apply to college and would sometimes struggle academically and socially.

Lindblom admits top students from elementary schools across the city based on an admissions test. Students like Freddy Lazaro.

Lazaro attended a charter school for kindergarten through second grade, but then transferred to Beasley, a gifted school in Washington Park. Lazaro got into Lindblom’s Academic Center in seventh grade and is now a senior.

“It was diverse and that’s what I liked about the school,” Lazaro said. “I was able to meet a lot of different people who came from different backgrounds.”

Latino students make up about 27% of Lindblom’s otherwise primarily Black student body, which includes just over 1,300 students.

Lazaro said it was a hard transition academically when he got to Lindblom because he was suddenly taking Chinese and pre-algebra. Initially, his grades weren’t the best, he said, but they got better over time.

Since joining “Colegio” as a sophomore, he said he’s been able to explore career options and visit a variety of colleges, including University of Illinois where he was recently admitted to the business school.

“Those college trips definitely influenced my post-secondary plans,” Lazaro said.

When Alaves first started “Colegio” six years ago, he recruited Latino boys with a 2.0 to 2.9 GPA. He would talk to teachers during team meetings and review freshman grades to identify students who might benefit from additional support.

“But it’s grown so much to where, it’s just word-of-mouth,” Alaves said. “They themselves share with their friends and will bring their friends here to my office, and they’ll say, ‘Hey, Mr. Alaves. I think that he’s a really great fit. I think that he would do really well in ‘Colegio.’”

Like his students, Alaves was a high achiever in elementary school and got into a prestigious high school: De La Salle Institute, the alma mater of many famous Chicagoans, including two former Chicago mayors, Richard J. and Richard M. Daley.

He went to Florida State University on a full scholarship because he felt like that was what was expected of him.

“In reality, I was first-generation, I had no idea what I was doing,” Alaves said. “I had never stepped foot on any college campus and a big, big environment like that was not the best fit for me.”

Alaves transferred and finished his degree in psychology at DePaul before landing a job at a nonprofit in Little Village, where he ran a youth program after school and during summers. After getting a master’s in school counseling and clinical mental health counseling, he became Lindblom’s counselor for the seventh and eighth grade students in the Academic Center.

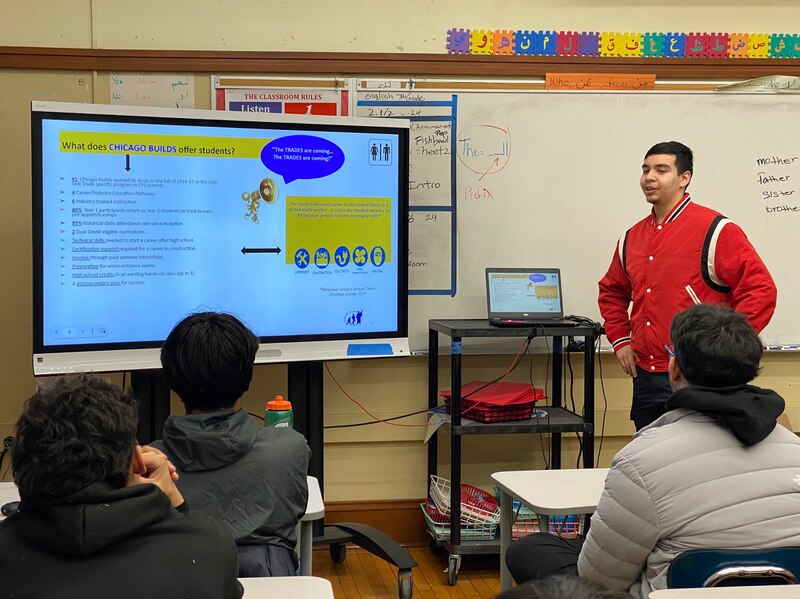

Shortly after the bell rang on Valentine’s Day, junior Eduardo Serna stood before his classmates to give a presentation about a program he’s part of this school year called Chicago Builds, a pre-apprenticeship program for high school juniors and seniors to learn construction trades, such as carpentry, electricity, welding, and HVAC.

Serna explained how his teachers are part of the electricians union and showed off pictures of a small house he built. Then he touted the pay-off.

“When you’re working overtime, you get 1.5 times pay and you can get double time hours as well,” Serna said. “Your salary can be well up to or over $100,000.”

Alaves chimed in to tell the group that Chicago Builds can help students get into competitive apprenticeships with the unions after high school.

“To get into a union, it is really, really, really competitive,” Alaves said, adding that there are 2,000 applications for about 200 spots every year. “They do want strong students. You can’t just give up on high school and say I’m going to do a trade. If you’re thinking about the trades, you still have to be doing well academically now and keeping your grades up.”

Serna said he plans to get his bachelor’s degree in business and hopes to one day run his own construction or trade company.

As the class period came to an end, Alaves reminded the boys to return their permission slips for the group’s upcoming visit to Roosevelt University while he handed out black sweatshirts. Emblazoned on the front, in the school’s maroon and yellow colors, were the words: “Lindblom Colegio.”

Wear these shirts proudly, he told the boys. They represent the school and the values of the “Colegio”: Be on your best behavior. Be respectful. Be on time to class. Keep your grades up and ask for help when you need it.

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.