This story was originally published in Block Club Chicago.

All is quiet inside a Humboldt Park elementary school filled with student artwork, class pictures and flags — except for one classroom, where there’s soft chatter in English and Spanish.

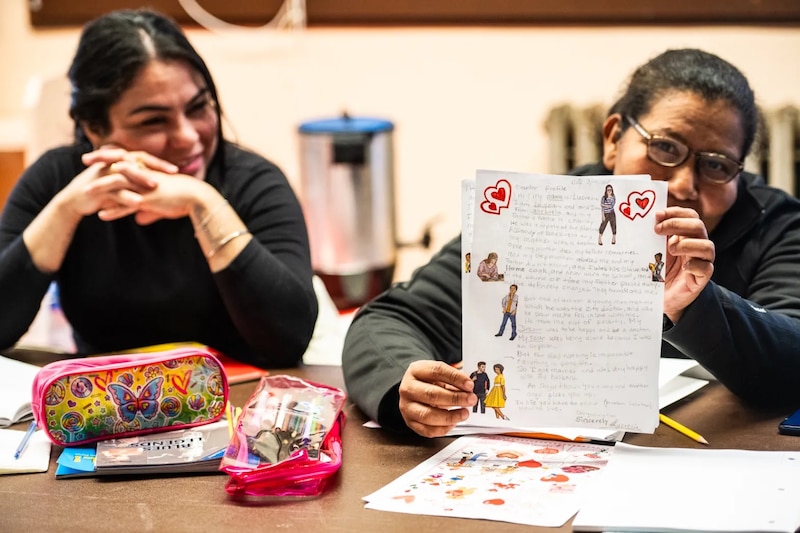

It is home to Lowell Elementary School’s first English as a Second Language class, where about 15 parents and relatives of the school community meet Tuesday and Thursday mornings.

The group is a mix of new arrivals from Latin America, mothers, and relatives from other countries who wanted more opportunities to practice English, help their children with homework, and integrate into the neighborhood.

For some, learning English is also their ticket to getting a job and enrolling in college classes to further enrich their lives in Chicago, they said.

“I want to learn English so I can go to school and get a degree and acclimate here,” said Francelys Tineo, who arrived from Venezuela a few months ago and whose daughter attends Lowell. “My husband is trying to get work while I am in class, but we can’t work here yet. But I want to better communicate with people when I can get a job.”

Like many Chicago Public Schools, Lowell, 3320 W. Hirsch St., has seen an influx of migrant children enroll over the past year, growing its already high Latino student population, according to school data. The school has 304 students, 95% of whom are low-income students and 38% of whom are English learners, data shows.

Data on how many new arrivals have settled into Lowell since last year was not available, but the district has welcomed about 5,700 newcomers in collaboration with the city’s family services department, a CPS spokesperson said.

Noelia Llamas, who has lived in Humboldt Park for 18 years and is from Mexico, is on Lowell’s bilingual board and is a member of the school’s parent advisory council. She was one of the mothers who pushed the school to offer the program, she said.

As the Spanish-speaking parent group grew, they kept asking school officials what could be done to have more opportunities to learn English that fit their schedules, she said.

School liaison Maya Bral reached out to Literacy Chicago — a volunteer group that offers free English classes, digital literacy and workforce skills to adults — to see if it could send a teacher to the school.

The school began a partnership with the nonprofit in November, making Lowell one of the first CPS schools to offer the free class after the pandemic, Bral said.

“We need parents to learn and get practice writing and speaking in English so we can get more confidence, help our kids with homework and get more involved with the community,” Llamas said.

The attendance and level of engagement from parents has greatly benefited the school community, Bral said.

“Teachers are reliant on the teachers as much as the teachers are reliant on the parents, so I think (the class) has helped foster that sense of community even more and a sense of agency for the parents,” Bral said.

Many who attend the class told Block Club it has helped them boost their confidence, let go of fears in pronouncing words incorrectly, and create lasting friendships and a greater sense of community.

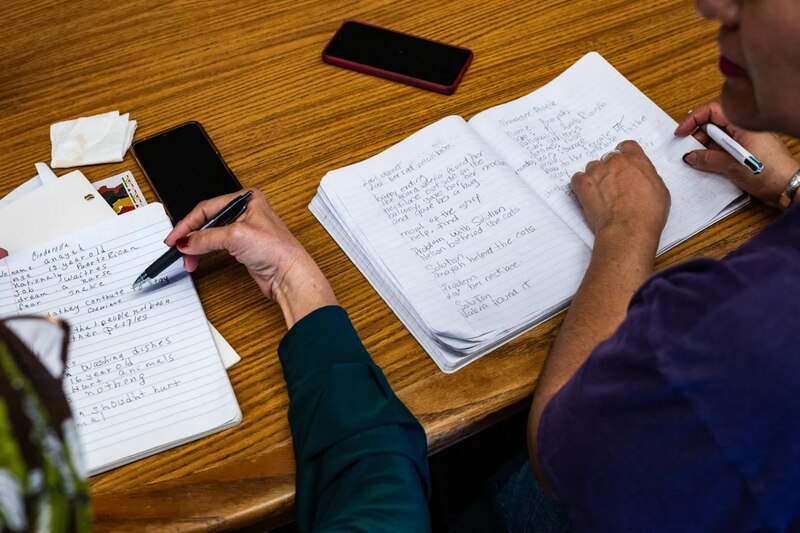

Progressing from basic skills such as directions and letter pronunciation to more complex skills like reading and writing in English has given parents a valuable opportunity — and it’s free and accessible, parents said.

Carmen Tello, who is from Ecuador and has lived in the neighborhood for eight years, said the class has helped her come out of her shell and strengthen communication with her son.

“I need to communicate with my son and my community and with people from the school who help him, even doctors, so it’s very important to have this skill and train my English,” Tello said. “In all the jobs I have had, everyone speaks Spanish, so there has been no need to learn English, but now I want to. … I am still scared, but I try anyway. Now I have more confidence in speaking and pronouncing words correctly.”

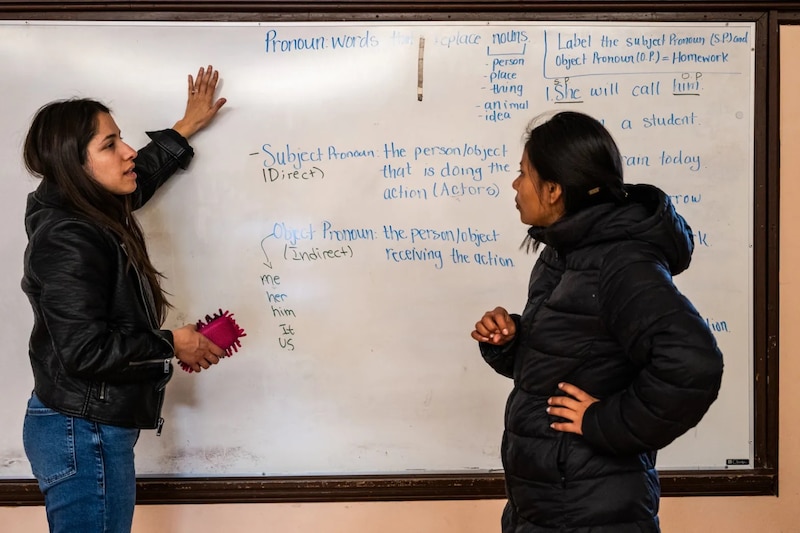

From the other side of the classroom, teacher Marisol Guzman has seen the women blossom and feel more powerful in their language skills, she said.

Through Literacy Chicago, Guzman has taught English literacy classes for three years around the city, and she has seen how the classes can empower attendees.

“There is something really powerful of just saying the words, even if it doesn’t sound right, just moving your tongue,” she said. “It’s a blessing to see them try, and putting themselves out there is powerful and very beneficial to them, as well.”

Guzman teaches all of her classes in English for a full immersion and only switches to Spanish as a last resort, she said.

“I like to challenge them and get them to work together, because I won’t always be here,” Guzman said. “If we have a new student, they may feel lost and need help, but others have been here a long time and can help, which is a good lesson and good to have a mix of learning.”

Llamas, who works with the school’s parent council to organize events at the school and the park, said the class has broadened her horizons. She hopes the class can help more parents looking to get more involved with the community and assimilate.

“I’ve been here 18 years, and it’s never too late to learn,” she said. “I know English, but this has helped with my pronunciation and confidence a lot. I am grateful.”