Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

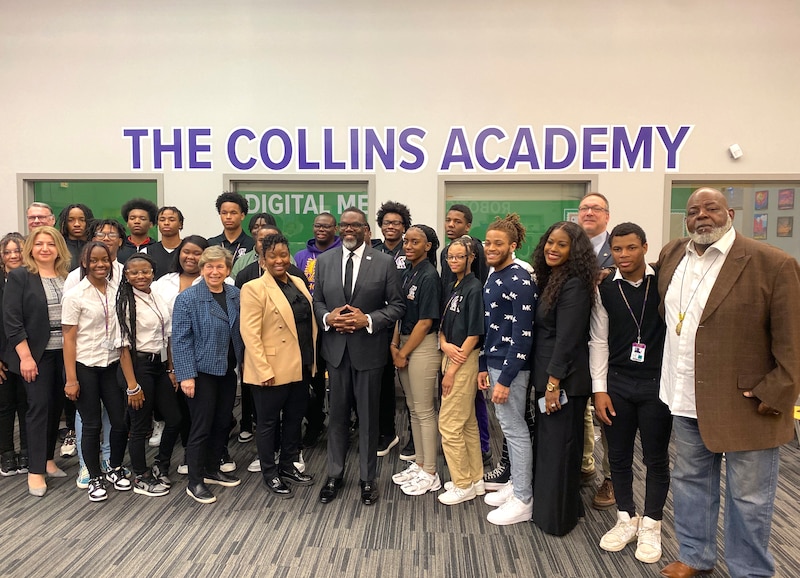

Sitting in a circle with dozens of students at Collins Academy on Chicago’s west side, Mayor Brandon Johnson asked a straightforward question: “What do you need?”

Melvin Hines, a soft-spoken junior in purple track pants and a black zip-up jacket, chimed in: “More resources, better opportunities, and more exposure.”

Answers from other students ricocheted around the room like a pinball: a law program, more connections to businesses, a grocery store in their neighborhood.

“Sometimes it feels like the only thing that’s available for us are leftovers, right?” Johnson said, nodding.

The roundtable discussion — organized with the local, state, and national teachers union, including American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten, as well as district leaders — gave the mayor and his allies a moment to advocate for expanding Sustainable Community Schools. The concept provides up to $500,000 a year to a school to partner with a local nonprofit on before- and after-school programming, community outreach, parent engagement, and other wraparound services.

Johnson has promised to grow the number of Sustainable Community Schools from 20 to as many as 200, possibly including Collins. It’s one of the ways he wants to invest more in neighborhood schools.

“This is about making sure that every single child has a library or librarian, wraparound services, class sizes that are manageable,” Johnson said. “There’s a lot of work to be done, but unfortunately, because of a long history of systemic racism, disinvestment has left our communities in despair.”

But Chicago Public Schools faces a $391 million shortfall in its $9 billion-plus budget next school year. The district is about to begin contract negotiations with the teachers union and officials recently sent principals individual school budgets using a new formula that provides set staffing levels and extra money based on need. Officials say the total amount distributed to schools is not decreasing, but individual campuses could see cuts.

Stephen Mitchell, the local school council chair at Bronzeville Classical Elementary School, a selective enrollment school that opened in 2018, said their budget is seeing reductions. He said it’s possible the school has to either let staff go or cut other resources.

“I think this is kind of pitting one against the other, which I don’t think is right,” Mitchell said. “I think we need to adequately fund our neighborhood schools and continue to fund selective enrollment schools.”

State lawmakers are moving legislation to block Johnson and his hand-picked school board from making “disproportionate” budget cuts at selective enrollment schools and also extend a moratorium on any school closures until 2027, when a fully elected school board is in place.

The bill passed out of the House late Thursday and is headed to the Senate.

CTU President Stacy Davis Gates characterized the bill with a handful of strong words — racist, disengaged, silly, an abomination — because it targets an issue “that does not exist.”

“There was a resolution that said that the Chicago Board of Education was going to finally prioritize Collins High School … and then you get a bill that says you can’t do that,” she said. “Everyone who votes for that bill needs to go into that room and engage with the same group of students that we just engaged with and explain to them why they cannot have more.”

Johnson, Davis Gates, and Mitchell, the Bronzeville parent, said Springfield should be focused on fully funding all public schools through the evidence-based funding formula approved in 2017.

That formula promised to get all Illinois school districts, including CPS, to “adequate” funding by 2027 by adding $350 million in new money for K-12 education every year. Since that time, the amount of state money allocated to Chicago schools annually has grown by more than a billion dollars. But the formula says CPS is still another $1 billion short of “adequacy.”

During the roundtable discussion with the students at Collins, Johnson and others, including the local alderwoman Monique Scott, whose dad and brother both served on Chicago’s school board, told the students they were advocating for more money from the state.

As the conversation wound to a close, Collins senior Marshall Douthard Jr. raised his hand.

Everyone has been talking about “the resources and the money problems,” Douthard Jr. said. “I would like to know when they come through: How do you plan to fulfill these requests?”

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.