Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

In a classroom normally filled with teenagers, 16 adults sat at desks arranged in a U-shape on a recent Saturday afternoon at Roosevelt High School on Chicago’s North Side.

Behind the group, there was a small table with a box of red, green, and yellow wristbands. Green meant you were fine with hugs; yellow OK’ed high fives and fist bumps; and red meant “no touching, send vibes!” according to a sign taped to the table. Next to the wristbands were a stack of packets that said “Effective School Boards Framework.”

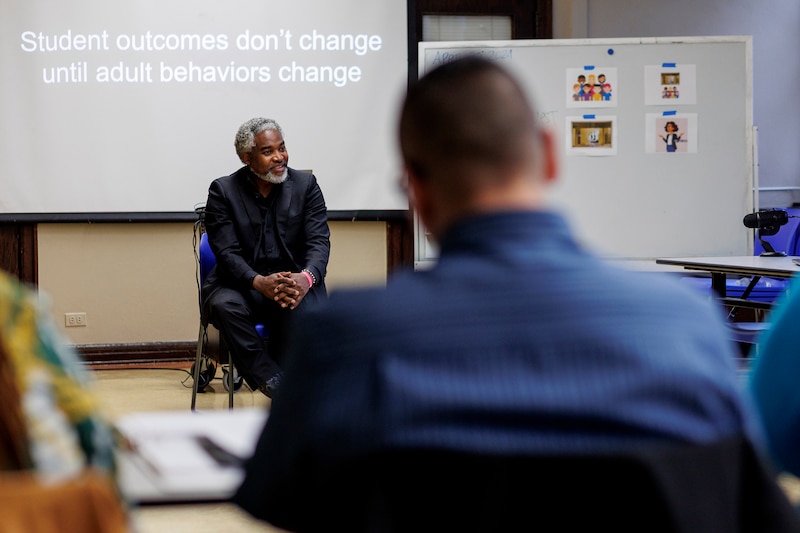

At the front of the class, a projected slide said in big letters, “Student outcomes don’t change until adult behaviors change.”

It was time for lessons on how to be on a school board.

AJ Crabill, an author presenting to the group that day, asked the class: Who is at the top of the organizational chart of a school system?

It’s not the school board, he said.

The superintendent, someone wondered.

“It is 1,000% not the superintendent,” Crabill said.

The mayor?

“It’s definitely not the mayor.”

Students?

That would be “beautiful,” Crabill said, but that’s not how it works typically.

The correct answer: The community.

Crabill, director of governance for the Council of the Great City Schools, was explaining to the class of education advocates, parent leaders, and prospective school board members that any school system exists to serve the public — but sometimes policymakers forget that.

“The moment you realize the community is at the top of the org chart, and then you realize, ‘That seems completely incongruent with my lived experience,’” Crabill said, drawing some laughs.

The students are the inaugural class of a new, eight-month fellowship launched by National Louis University to prepare people for Chicago’s first elected school board, said Bridget Lee, the fellowship’s executive director. The fellowship is funded by Crown Family Philanthropies, The Joyce Foundation, the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, and Vivo Foundation (Crown, Joyce, and Vivo also support Chalkbeat. Learn more about our funding here.)

Known as the Academy for Local Leadership, or ALL Chicago, the fellowship is happening at a critical time. Chicago voters will begin electing people to the city’s school board this November, and candidates are building campaigns. But Lee said the program is for advocates as well as potential candidates.

Fellows had to apply to join the program, which began in March and will last through November and are hosted across the city, said Lee, who added that they are still figuring out the timing for the second cohort of fellows. Fellows are given a $400 stipend to help cover transportation costs — an amount Lee hopes will increase in the future, she said.

Over about two sessions a month, the group will learn the basics of Chicago’s school system, the district’s finances, and how to make an “action plan” for creating change in school communities.

Towards the end of the program, fellows will flesh out their actual action plan and present their vision for change during their graduation ceremony. By then, some of the fellows who are running for school board may have won their elections.

The first group of fellows includes a handful of people running for office and many with close ties to the district. It includes Sendhil Revuluri, a former board member; Danielle Wallace, a school board candidate running in District 6 on the South Side; and Mykela Collins, a mother with two children in Chicago Public Schools who serves on a Local School Council.

Wallace, a former teacher and nonprofit leader in Englewood, was on the fence about running for school board until she started the fellowship.

“One of the most valuable things for me is becoming really clear on what my thoughts and values and positions are on different topics,” Wallace said. “That just gives me a lot of confidence on making the right decisions from that seat.”

Fellows Jesus Ayala Jr. and Carlos Rivas have also filed campaign finance paperwork to run for school board seats in District 7 on the South West side and District 3 on the North West side, respectively.

Collins said she applied for the fellowship because she wanted to know how to be a better advocate.

“I wanted to know who is important for me to go to, the type of questions I can ask and needed to ask and how I can go about getting those answers,” Collins said.

Lee’s idea for the fellowship formed three years ago, when Illinois lawmakers first passed a law creating the elected school board. As a former teacher and CPS employee who worked in the central office, Lee wondered how the public would learn about the complicated new governance system. Lee then visited a program in Cincinnati called School Board School, which educates school board candidates and advocates, and decided to bring the model to Chicago, she said.

Lee said “plenty” of organizations help political candidates navigate politics. ALL Chicago focuses instead on learning about the school system and how to work with people who may not agree with you — just like a school board.

For example, this first batch of fellows sees eye-to-eye on about 80% of things: They care about children, and they want all students to succeed regardless of their backgrounds, Lee said. She wants the fellowship to be the place where people can have “productive civil discourse” about the 20% of things they don’t agree on.

“I think that fellows are sort of learning from each other, like how their own stories and their own experiences have shaped their viewpoint and how the system should run and are learning how to talk about that in a way that moves things forward,” Lee said.

Since the program began in March, the group has already heard from some experienced policymakers, including former Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson, Lee said. They’ve also started to create their plans for how they want to impact the school system.

On the Saturday afternoon when Crabill was there, however, the fellows went back to the basics.

He asked the group to ponder some big questions, such as, “Why do school systems exist?” Answers varied. One person said the goal was to prepare children for the workforce. Another said school systems also help students socialize.

After learning that the community is at the top of the organizational chart, Crabill, who wrote the book, “Great On Their Behalf: Why School Boards Fail, How Yours Can Become Effective,” emphasized another basic fact of being an elected official: Your job is never over.

“You gonna be sittin’ up in the grocery store trying to find a non-squishy avocado, and somebody gonna come up to you and complain about, how come their kid didn’t get a part in the play?” Crabill said, igniting laughter across the room.

But, seriously, he said: “This becomes your life. People will roll up on you at any moment when you have put yourself in the position to be their representative — and I think it’s perfectly appropriate for them to do so.”

The fellows’ knowledge of Chicago Public Schools varied. One person talked about the district’s school bus crisis. At one point, one fellow informed another that Chicago Public Schools had scrapped its old school rating policy last year. The second fellow replied, “Thank God.”

Other times, fellows had some universal experiences with CPS. For instance, during a discussion about public feedback, the class started talking — and commiserating — all at once about the process of signing up for public comment during monthly Chicago Board of Education meetings.

“You gotta sign up two days in advance and it finishes in two minutes,” one fellow said.

“Yes!” another replied.

School board members should never only consider public feedback during a meeting, Crabill said, given that most people in the community won’t be represented there.

Crabill also covered the murky line of when board members should step in to solve a problem or delegate to someone else.

He asked the group to imagine a class of 26 students where six of the children have higher needs and get more attention from the teacher. Now imagine that a father of one of the other 20 children calls a school board member he knows, asking for more attention for his child. The board member then calls the teacher to fix the problem. What is the teacher going to do?

One fellow’s answer stood out: “Spend more time with that one kid,” she said.

That’s probably what would play out – but Crabill warned the group to never let that happen. School board members should be pointing the parent to the proper channels for expressing their concern instead of giving them inequitable access to power and frustrating their employees in the process.

“We’ve created a hostile work environment for our staff that pressures them to no longer do what in their judgment is the best interest of children but instead do what is in the best interest of the power that be that showed up,” Crabill said.

This lesson was enlightening for Collins, the mother and LSC member.

“Learning that the roles and the responsibilities and accountability of the board is so much different from what I ever thought,” Collins said. “I thought that the board is supposed to do everything…anything goes wrong in the school, it’s the board’s issue, but learning that’s not how it is and they delegate different folks throughout the district to make those changes.”

During the session, fellows had a meta moment. They realized that so much of what they’re learning about the school system isn’t common knowledge to the general public. Was there a way that the system or a future board could spread what they’re learning?

Crabill challenged them.

“This is a new scenario for Chicago,” Crabill said, “so write a new script.”

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.