This story was co-published with Block Club Chicago.

A couple months after enrolling, a few dozen migrant students were struggling to adjust to life at Kenwood Academy on the South Side.

The teens had landed in a school where few people speak Spanish, their native language, and the classrooms they were put in were “a mess,” teacher Maggie Ritthaler said.

“Kids were throwing things, punching each other, playing around — and the teacher was barely speaking Spanish,” Ritthaler said.

Ritthaler and another teacher, Zachary Hill, made it their mission to help: The two Spanish-speakers moved their schedules around to teach classes of migrant kids and got their principal to hire part-time student teachers.

Still, about 85% of Kenwood’s students are Black, and the school hasn’t historically served many students whose first language isn’t English. So the newcomers still aren’t getting the language help and emotional support they need, the teachers said.

“We provide a safe home base for them in school, but at the same time, the needs they come in with are more than we are prepared for or licensed for, or that we have resources for,” Ritthaler said.

In May, a Block Club and Chalkbeat investigation found many migrant students are landing in segregated schools like Kenwood with few if any bilingual resources. The so-called “language deserts,” concentrated on the city’s South and West sides, have left many migrant kids feeling lost in school while teachers scramble to meet their needs.

But experts and teachers union leaders say the district could help the migrant students with a different approach: hiring “newcomer liaisons.” As envisioned by the Chicago Teachers Union, the liaisons would help ease the burden on teachers and other school employees who, in addition to their regular duties, are managing newcomer students’ behavioral and emotional needs while also helping them find health care and clothes.

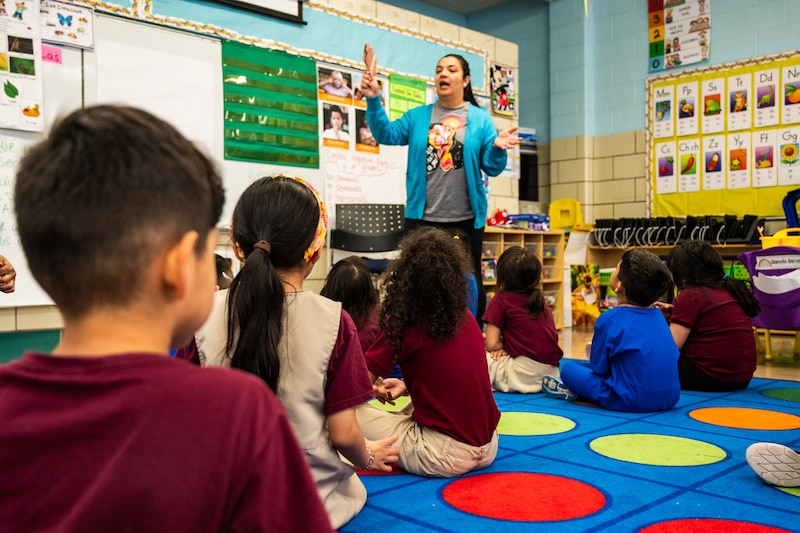

The liaisons would also provide language support to migrant students who are enrolled in schools where few people speak Spanish, such as Laura S. Ward Elementary School in West Humboldt Park, where a kindergarten teacher and two custodians are translating for the whole building, Block Club and Chalkbeat found.

School districts across the country have been able to help migrant students with liaisons, said Alejandra Vázquez Baur, who leads the National Newcomer Network, a coalition of educators, researchers, and advocates that works to address newcomer student inequity.

While it will take a lot more to overcome the Chicago Public Schools’ long history of failing English learner and immigrant students, the liaisons would be a step in the right direction, she said.

“You get these newcomer liaisons in sooner rather than later and they can help,” Vázquez Baur said. “Students can at least get in the best programs for them, [they can be] aware of their options, their rights are upheld, things are translated and interpreted for them so they can make the best decisions for their futures.”

A go-between for migrant families and schools

Under the Chicago Teachers Union proposal, “newcomer liaisons” would be in charge of migrant student enrollment, programming, communication between families and teachers, and other duties that require bilingual services, like translating Local School Council meetings, union leaders said.

Those duties currently fall to teachers like Ritthaler and Hill who have a myriad of other responsibilities. Ritthaler is a Spanish teacher who chairs Kenwood’s world language department, while Hill is the school’s English language program teacher.

“What usually happens is [those teachers] are trying to do that either in their off time or they’re not providing the required services to kids because they’re doing those things,” said Julie Sugarman, associate director for K-12 Education Research at the Migration Policy Institute’s National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy.

In other school districts that use the approach, liaisons are “local folks, maybe parents, maybe community advocates” who can communicate with new families and explain their rights, but don’t necessarily need teacher certifications, Vázquez Baur said.

Other districts have used a patchwork of funding — local, state, and federal dollars — to cover the program, experts said.

Union leaders didn’t answer specific questions about their proposal.

CPS officials also didn’t respond to questions, saying only that the district has received the union’s proposals and is reviewing them.

A list of the district’s initial proposals does not include “newcomer liaisons.”

The district needs ‘more bilingual support on every level’

“Liaisons” alone won’t be able to fix all the problems faced by under-resourced schools serving newcomers.

As of April, nearly 9,000 migrant students — many of them fleeing turmoil in South and Central American countries — had enrolled with the Chicago Public Schools. The vast majority of the new students don’t speak English and are living in temporary housing. Many have spent limited time in school and are grade levels behind for their ages.

Thousands of migrant families are getting apartments in historically Black neighborhoods like South Shore and Austin through a state rental assistance program. From there, children are enrolling at schools that haven’t historically served students whose first language isn’t English.

In addition to a lack of language support, many families are struggling with long commutes and are unaware of their rights and options, Block Club and Chalkbeat found.

All of this comes after the district has struggled for years to fully comply with state and federal laws around bilingual education.

Chicago Teachers Union president Stacy Davis Gates said newcomer families are experiencing “what it feels like to be a Black family in Chicago public schools.”

Segregated Black schools on the South and West Sides, where many migrant students have landed, have for years faced declining enrollment and a dearth of resources, the union said in a written statement. Meanwhile, some Latino schools have seen their budgets slashed in recent years as a lack of affordable housing has led to declines in enrollment.

“This is the context for the influx of newcomer students — a reflection of how CPS has lacked funding and support for Black and Brown students, and why this is so key to our contract negotiations,” union leaders said in their statement.

Those negotiations are the CTU’s first since the election of Mayor Brandon Johnson, a former organizer for the union. Adding resources for migrant students is one of the union’s key demands.

The union is asking for “more bilingual support on every level,” the union statement said.

On top of “newcomer liaisons,” the union is pushing for more bilingual and multilingual teachers; more dual-language programs, which offer English learners and native English speakers instruction in Spanish and English; and an expansion of the district’s Sustainable Community Schools model.

Launched in 2018, that initiative enlists community organizations to bring programs and services to high-poverty schools struggling with low enrollment.

CPS CEO Pedro Martinez has said the district wants to expand dual-language programs, and Mayor Brandon Johnson named growing sustainable community schools as a top priority for his administration.

The union also wants “staffing and support for language access needs around early education, IEPs, guest teachers, clinicians, access to Pre-K and other high-needs areas,” along with “training and support from the Board of Education for migrant students on a yearly basis, including funding for immigration support,” according to a list provided by the union.

Union leaders didn’t respond to questions asking for more information about these proposals. The union’s current contract expires at the end of June.

‘The most traumatic journey they’ll ever go through’

Calls for more support for migrant students come as the district faces a large budget shortfall for the next fiscal year, which begins July 1.

With pandemic relief dollars drying up, the district is facing a nearly $400 million budget deficit while the state has its own financial challenges.

Lawmakers recently approved a state budget with an increase of $350 million for K-12 funding, the minimum under the law and $200 million less than education advocates had asked for. And the General Assembly didn’t approve a proposal that would’ve sent more money to school districts that have received an influx of migrant students.

CPS officials have said they’re trying to cut expenses at the district’s central office, but Martinez recently told reporters they’re still figuring out how to close the deficit.

At Kenwood, Ritthaler and Hill are wrapping up the school year exhausted and demoralized.

They spent the year “in survival mode,” scrambling to find Spanish-language activities and assignments, distributing donated clothes and food and providing counseling.

“We’re receiving these kids who’ve just gone through the most traumatic journey they’ll ever go through, and we’re kinda just plopping them into biology class,” Ritthaler said.

“This isn’t just getting 30 new students. This is 30 new students who are coming from a completely new world … and we’re not equipped to serve them the best way they need to be served.”

Mina Bloom is an investigative reporter for Block Club Chicago. Contact Mina at mina@blockclubchi.org.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.