Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

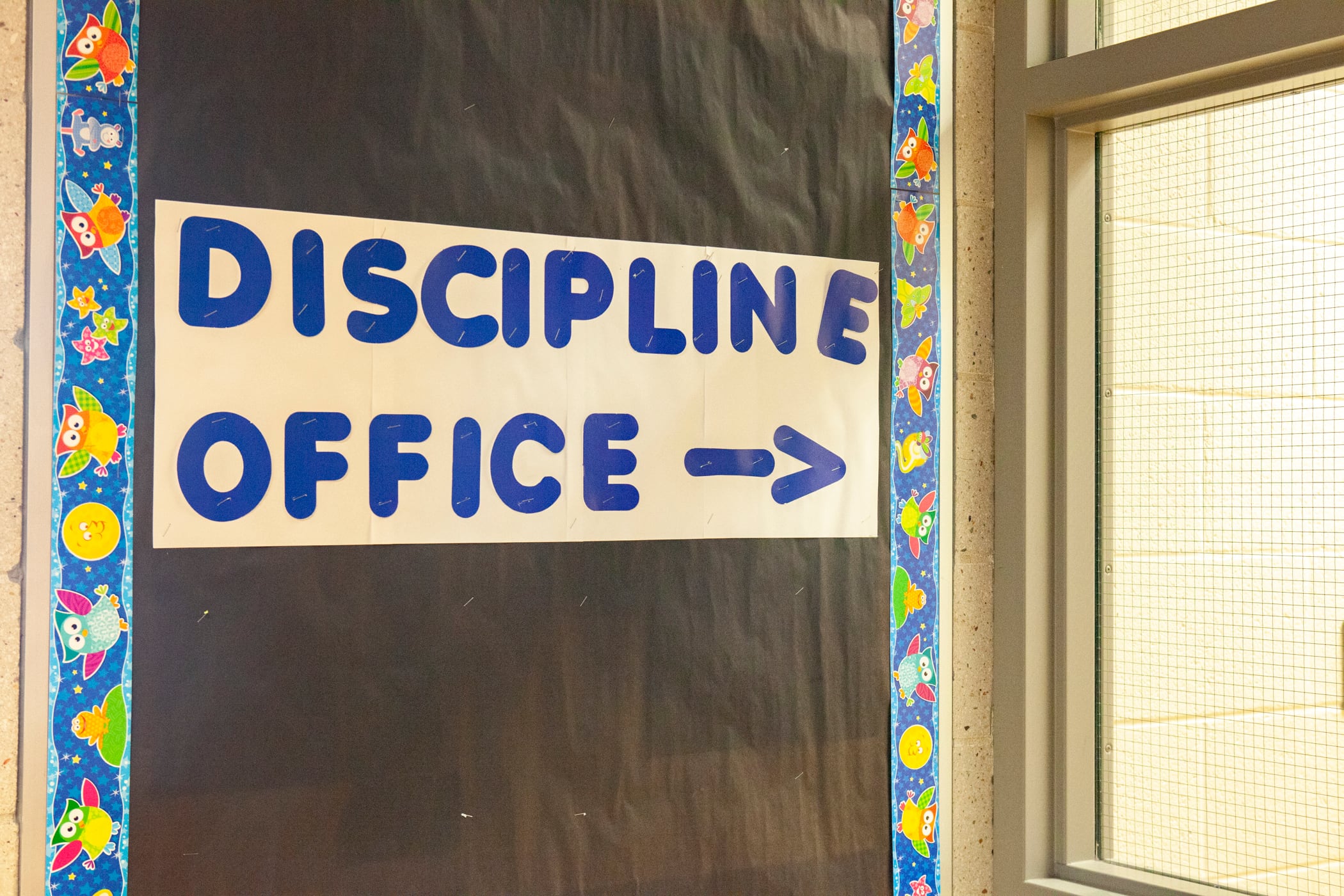

Chicago Public Schools is overhauling how it tracks disruptive behavior by students in pre-K through second grade and how it communicates with families about such incidents.

Under student code of conduct changes the school board is slated to approve this week, schools would only flag behaviors that represent a serious safety issue, such as bringing a weapon to school. And letters alerting parents about these behaviors will no longer refer to “misconduct” and code of conduct “violations” — language district officials said stigmatized young children and failed to reflect their social-emotional development.

The proposed changes are part of a broader district move away from punitive discipline.

The district largely eliminated suspensions in pre-K through second grade a decade ago. But schools have continued to track disruptive behaviors for young students using the same six categories of severity used for older students. Under the proposed changes, the district will do away with those categories in the early grades and only monitor seven behaviors, which also include repeatedly destroying classroom property or injuring a classmate or teacher.

Benjamin McKay, director of restorative practices and student discipline support, said his team heard from educators who said it felt wrong to send letters to the family of a 5-year-old titled “Misconduct Report.”

“Parents were taking offense to that,” he told Chalkbeat. “The policy shift will be setting educators up for success, not eroding trust and pushing problematic language.”

The move comes after the school board voted earlier this year to remove police officers from schools and embrace a “whole school safety” approach that leans more heavily on restorative justice practices and other non-punitive measures. District leaders have noted that punitive discipline has disproportionately affected Black students and students with disabilities.

The proposed code of conduct changes would also more clearly spell out federal safeguards against excessively suspending all students with disabilities, which generally limit out-of-school suspensions to no more than 10 days each school year.

Chicago has almost eliminated early grade suspensions

Chicago Public Schools did away with suspensions in preschool through second grade in 2014 — with one exception. A district official who oversees networks of schools can sign off on a one-day suspension in situations when school leaders fear a student presents a danger to peers and staff.

In the school year before the change took effect, schools suspended students in those grades about 2,240 times, including 1,830 out-of-school suspensions. That was out of more than 5,000 times that students were flagged for misconduct under the student code of conduct that year.

Suspensions in the early grades plummeted in the following school years under the new policy. During the 2022-23 school year, the most recent for which data is readily available, five suspensions involved students younger than third grade.

But the district continued to report students in those early grades for misconduct. More than 2,780 were flagged in 2022-23, including about 180 in the two most serious categories, considered “major misconduct.”

In an interview with Chalkbeat, McKay said some behavior by young students does pose a serious threat to safety on campus, and it’s important that schools continue to track it and inform families about the steps their school is taking to address it. But in those early grades, it makes sense to focus on monitoring only these most serious behaviors and to communicate with parents using more neutral language that avoids words such as “misconduct.”

“Language is critically important, and that’s at the root of our changes this year,” McKay told the school board at a recent meeting to review this week’s school board agenda.

Board members applauded the proposed changes, saying the new code of conduct language better reflects the district’s values.

“We know these labels of misconduct carry through a child’s elementary and potentially high school experience,” said member Michelle Morales. “When young people aren’t labeled as ‘misconduct’ or ‘behavioral issues’ early on, I’m going to be intrigued to see what that means for the whole child and what that means for their mindset and their family’s mindset.”

Some research suggests Chicago’s shift is on the right track

A number of districts and states have also largely eliminated out-of-school suspensions for students younger than third grade. Those bans were part of a broader move away from punitive discipline in the 2010s, inspired by research showing suspensions can hurt students’ academic prospects in the long run and disproportionately affect students of color and low-income students.

But post-pandemic, some states and districts rolled back restrictions on punitive discipline amid a rise in disruptive behaviors after students returned to classrooms following school shutdowns. McKay said navigating that disruption explains why the district did not adopt the proposed code of conduct changes sooner.

Still, Chicago officials are staying the course with restorative practices.

Separately from the code of conduct revisions, Chicago’s new safety plan, which is open for public comment, eliminates school resource officers, calls for teaching students social-emotional skills, and requires training for educators on practices that reduce suspensions and expulsions. This spring, state lawmakers introduced a bill that would preserve local school council’s ability to staff police officers, arguing they are key to maintaining safety on some campuses. But the bill didn’t go anywhere during the legislative session that ended earlier this month.

One study found that after a Maryland ban on out-of-school suspensions in kindergarten through second grade, schools did not appear to experience a rise in in-school suspensions or a dip in student achievement — though racial disparities in discipline did not decrease.

Rachel Perera, a researcher at the Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings, also noted a recent study that found ending early grade suspensions in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools did not affect test scores or the number of disciplinary incidents.

“Opponents of suspension bans often claim that these reforms will lead to increases in misbehavior and disruption—a claim that hasn’t borne out in the data,” Perera said, adding that the overwhelming majority of students in those early grades get suspended for non-violent infractions.

Research also stresses the importance of consistently helping schools as they shift away from more punitive discipline, she said. Studies have shown promise for restorative practice in reducing disruptive behavior, notably a 2023 University of Chicago report on the rollout of such practices in Chicago high schools.

But, Perera said, “This work also underscores the importance of investing in training and supports for schools transitioning to alternative approaches like restorative practices.”

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.