Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

Danielle Wallace is a single mom from Englewood who decided to run for Chicago’s first elected school board – exactly the type of person some, including former CPS CEO Janice Jackson, argue should win a seat.

Wallace spent three months this spring going to different churches and community events to convince her neighbors that she could be a school board member who represents their needs. She got the 1,000 signatures required by state law to get on the Nov. 5 ballot, but shortly after submitting them in late June, she learned someone had challenged their legitimacy. District six, where Wallace is running, is one of the districts that has the most candidates being challenged.

With little money in her campaign fund, Wallace, a former school teacher who now works for the youth-focused nonprofit she founded, decided to withdraw and instead try to run as a write-in candidate. Wallace said she did not have the time or money to hire a lawyer, which could cost thousands of dollars.

This, she thought, is “why regular people won’t run for this office.”

Since the elected school board bill was signed in 2021, Illinois lawmakers and local community groups have tried to figure out how to get people like Wallace, not just career politicians, on it. Parents who could represent working-class Black and Latino students that make up the majority of the school district. So far, political novices like Wallace and others have found it difficult to navigate petition challenges, fundraise, and balance their day jobs while campaigning. Several candidates have already been booted from the ballot.

The task of running successful campaigns is proving to be harder for some parents or community members concerned about students’ education without having strong political ties or backing from moneyed interests.

According to the Chicago Board of Elections, three candidates have withdrawn from the race, and the board voted to remove two more candidates for failing challenges to their signatures.

Recruiting family and friends to help get petition signatures

Collecting signatures was a “steep” challenge for West Loop attorney Jousef Shkoukani, who is running in District 5. It required him to enlist his wife, in-laws, and friends to help between March 26, the first day candidates were allowed to get signatures, and June 24, the deadline to file.

Shkoukani visited parks and grocery stores, from 6-9 p.m. or on weekends when he wasn’t working. Jason Dónes, a former teacher running in District 3, visited playgrounds and knocked on doors and would sometimes need someone to watch his kids as he gathered signatures.

Both said they enjoyed meeting voters and hearing their concerns. But it was also an unfamiliar task, where the so-called “playbook” for political novices was essentially the Board of Elections website, Dónes said.

Across town, Wallace faced her own hurdles. The day before her petitions were due in June, someone broke into Wallace’s car, according to Wallace and police records. The culprit snatched all of her petitions and her nephew’s sunglasses, she said. Her nephew reported the incident to the Chicago Police Department and officers were able to retrieve her petitions within 24 hours, she said. Officers arrested a 34-year-old man and charged him with criminal trespassing into a vehicle and theft under $500, according to online arrest records.

“I was like, ‘Are you serious right now? Why would you be trying to steal some petitions?’ This is a school board election!,’” said Wallace. ‘I didn’t get it.”

After collecting the required signature amount, Shkoukani celebrated by grilling burgers for his friends and family. But that elation died down when Shkoukani discovered he was facing a petition challenge, which calls into question whether a candidate’s signatures are valid. He and 26 others, including Wallace and Dónes, would have to go to the city’s Board of Elections to fight against the challengers.

Wallace wishes she would have gotten three times more signatures to stay on the ballot.

In Wallace’s District 6, four other hopeful candidates needed to collect at least 1,000 and no more than 3,000 signatures to get on the ballot. That means at least 5,000 residents in that district, but no more than 15,000, could sign petitions – and each of them can’t sign more than one petition, according to state election law. If a registered voter is found on multiple petitions, their signature can be deemed invalid.

Dónes said he knew to collect more than the required amount because of advice from two cousins who had helped collect signatures on other local campaigns.

Petition challenges knock candidates off the ballot

Shkoukani, who is an attorney, decided to represent himself for his petition challenge. But he said he had to brush up on election law, which he doesn’t practice.

When he went to his first hearing, Shkoukani didn’t have copies of his petitions, making it difficult to follow along. The Board of Elections provided him with a set within a few hours of him asking, Max Bever, a Board of Elections spokesperson, said.

Shkoukani took multiple days off work to attend hearings. But he was late to one hearing because he claims a receptionist told him of the wrong start time, meaning that he couldn’t dispute challenges to specific signatures while officials went through them. Bever said an elections official had informed Shkoukani and the rest of the candidates that the next day’s hearing was at 8 a.m., and no one but Shkoukani showed up late the next day. An online notice that was emailed to candidates also listed the time as 8 a.m., Bever said, but Shkoukani said he never received that email.

Given work and other obligations, his campaign hasn’t yet raised money, an effort he claims has been further hampered by the petition challenge process. That means many potential voters might not know who he is.

“You have jeopardized all of your time that you would otherwise spend campaigning and being out there, you’re really just trying to fight to stay on,” Shkoukani said.

Ross Secler, an elections attorney, said petition challenges can be difficult for novice candidates without a lawyer because they are fast-moving proceedings that can involve examining hundreds of signatures.

But that is also why he argues the process is fair. It’s “true due process” in which officials sift through individual signatures and allow people to challenge them, but also allows candidates to defend themselves. Proceedings are open to the public. In other states, government officials make calls on signatures in a back room, he said.

The system primarily exists to ensure that people who want to appear on the ballot “have that minimum level of actual support,” said Secler, who is representing Raquel Don in District 7, who is being challenged but declined to comment on that case.

“It’s not the best system you could possibly ever have [but] I think for the most part it’s fair, and that’s really one of the key things — you’re gonna get a fair shot,” Secler said.

While petition challenges have resulted in knocking some candidates off the ballot, some survived their challenges and will be on the ballot in the fall, including Carmen Gioiosa, a candidate running in District 4 and the only candidate in that district to face a challenge.

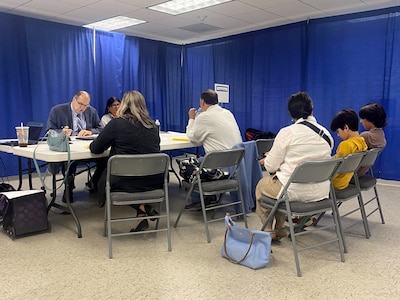

On July 17, Gioiosa seemed apprehensive as she walked into the room with her two children to sit in on her petition hearing. But as soon as she sat down, the challenger’s lawyer said that they would drop the challenge. Gioiosa looked surprised and relieved.

“I get to focus more on getting my name out and meeting families and students,” said Gioiosa when asked about her next steps.”I’m hoping to get a really good campaign off the ground and get some real good work done for our families.”

Now, Gioiosa goes up against five more candidates in District 4 vying for an elected school board seat.

The Chicago Board of Elections will issue more decisions in August on candidates who have been challenged and whether they can stay on the ballot. Candidates can then appeal those decisions, potentially bleeding past the time ballots get printed.

Who is behind the challenges remains a mystery

Challenging people’s petition signatures is something of a Chicago political tradition.

But candidates do not challenge their opponents directly. Rather allies or operatives will file objections and those objectors may be represented by an attorney, sometimes paid by the candidate. Even former President Barack Obama worked to remove his opponents from the ballot, allowing him to run unopposed in his first race for state senate in 1996.

For this first round of Chicago school board races, 40 objections were filed against 27 candidates. Some face multiple objections like Wallace. Chicago Board of Elections records obtained by Chalkbeat show the same set of four lawyers are representing objectors in 19 cases — including Wallace and Shkoukani.

Those attorneys — Michael Kasper, Steven Fine, Kevin Morphew, and Michael Kreloff — did not respond to Chalkbeat’s requests for comment. The attorneys are also listed as appearing on behalf of two candidates: Brenda Delgado and Jason Dónes. Delgado was removed from the ballot last week and Dónes’ case is still ongoing.

Dónes, from District 3, said he doesn’t know his objector. He said it’s been “frustrating” to see some of the signatures that are being challenged because he knows they’re real people, he said. However, he said he’s willing to do what it takes to stay on the ballot, including collecting affidavits from people whose signatures are in question.

Dónes said he’s fortunate that his nonprofit job is flexible enough where he can drop into proceedings around his work schedule.

Wallace is currently working to get her name out to voters in her district as a write-in candidate and fundraise for her campaign. So far on the campaign trail, she said, she’s trying to get people who see a write-in as a long shot to believe it is possible for her to win.

“I understand why people feel that way, but that’s not gonna deter me,” said Wallace.

Even though it is hard to run as a write-in candidate, she said, it’s even harder to sit back and watch children in Chicago schools not getting the support they need.

Becky Vevea contributed to this report.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education and the state board of education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.