Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

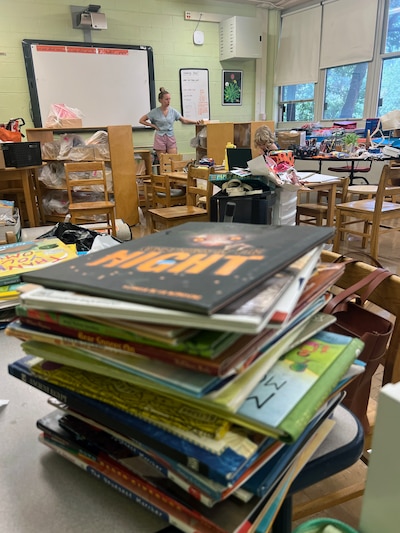

As a humming air conditioner tried to block out the last of summer’s humidity, a half-dozen tiny desks and tables were scattered all over Alli Bizon’s classroom at Suder Montessori Magnet Elementary School on Chicago’s West Side.

Plastic wrap covered supplies on wooden bookshelves, and the mint-green walls were mostly bare. A rug with printed leaves was rolled up.

Bizon thought: What should I move back into place first?

The task before her was the one she’s had for the past 15 years: Transform this mess into the organized classroom her students are used to seeing – one with neatly arranged desks, colorful props for learning math, and filled with books, framed art, and comfortable rugs.

When Chicago Public Schools students go back to class Aug. 26, they will likely walk into rooms with lined-up, clean desks and brightly colored signs on the walls. But few people see the days of work and personal expense that teachers like Bizon spend to get classrooms ready for that moment.

Preparation for the first day of school can involve moving furniture, cleaning, decorating, and taking stock of supplies in the last couple of weeks of summer break – much of which teachers do on their own, sometimes with the help of other staff, parents, or relatives.

At Suder, this year’s Democratic National Convention at the United Center, which is a half-mile from the school, almost threw a wrench into the process. Suder’s administrators initially told staff they may not have access to the school during the week of the convention from Aug. 19-22, potentially wiping out several days that Bizon and her colleagues could use on their rooms, she said.

So out of precaution, Bizon came into Suder earlier than usual with her 5-year-old daughter in tow because she couldn’t find child care.

“It’s very overwhelming and stressful and chaotic and dirty and messy,” said Bizon.

She quickly added: “And fun, also.”

Teachers ultimately do have access to Suder during the DNC, Bizon said. But she and some colleagues went in last week to set up to avoid traffic.

On this particular Wednesday, 12 days before the start of school, Bizon’s goal was to shift her furniture into the right places. The shelves and tables were moved during the summer so maintenance staff could wax the floors. Bizon’s bigger goal was to get the classroom ready by Friday, Aug. 23, three days before the first day of school.

Around Room 114, there were still signs of the last school year. On one wall, a small whiteboard read, “Happy last day!” Orange signs taped to the top of the broken Prometheus board said, “We care about ourselves” and “We care about each other.”

A stack of binders with student names on them sat in one corner of the room. As part of the Montessori model, Bizon teaches first through third graders, meaning the same students return two years in a row unless they move or transfer out.

As Bizon walked around her room, another teacher who was setting up down the hall walked in. Several parents were helping that teacher clean her room, where Bizon’s daughter, Autumn, would start kindergarten next week.

“You good?” the teacher asked Autumn, who nodded yes.

Bizon started moving shelves and tables – which she’s largely done by herself or with her husband’s help over the 15 years she’s been a teacher. The task is a bit like having “seven tabs open at a time,” because she always discovers a few more things to do.

As she moved a bookshelf out of its corner, she discovered translucent drip stains on the side. Milk from the last school year, she guessed, since this shelf sat near the trash can where kids would dump cartons. She’d need to clean that before stocking the shelves.

As she moved another bookshelf, she noticed the shelves were moving from side to side. She paused her pushing and pulled out a small hammer to bang the sides and tighten things up. Her daughter covered her ears.

When she flipped over a student desk, she discovered pen and marker drawings on the bottom. The rogue student art made her laugh.

Bizon saw classrooms get set up for much of her childhood. Her mother was a teacher in Trenton, N.J. As kids, Bizon and her siblings would help their mom get her classroom ready.

But years later, when it was Bizon’s turn to set up her own classroom for the first time, she felt lost. She recalls sitting paralyzed, “not knowing what to do next.”

Fourteen years later, she’s learned many lessons, including that the room should be clean and organized but doesn’t have to be perfect.

“I don’t need to worry about making sure there are pretty pictures on the wall and bulletin boards in a certain way because it’s about creating it with the children, so that can wait until later on,” Bizon said.

Bizon credited her principal for paying staff and giving them lots of options for which days they can come in to set up their rooms. Still, the task can feel daunting. Last year Bizon brought her other 1-year-old daughter in as she worked, which many of her colleagues do. On this Wednesday, Bizon fielded periodic questions from Autumn – and a request to play the “Nightmare Before Christmas” soundtrack – as she moved around furniture.

Bizon planned to ask some parent volunteers for help to clean or paint. She had scribbled down a five-column to-do list with more than a dozen tasks such as removing the projector and buying 25 clipboards.

“We are very lucky in that you send out a blast or email and say, ‘Hey, you wanna come scrub some shelves?’ And they’re responsive,” Bizon said of parents.

Preparing the classroom also raises questions about what supplies Bizon needs to find, get from the school, or just purchase on her own. Bizon, like teachers across the nation, pays out of pocket throughout the year to buy supplies or replace broken items the school might not be able to cover immediately in the middle of the school year.

She believes she spends at least $1,000 out of pocket annually on classroom supplies – double the national average before the pandemic, according to the National Education Association. She gets $300 of that back as part of a provision in the Chicago Teachers Union contract, she said.

Bizon, like many teachers, also has a Donors Choose page to fund supplies.

Bizon said she’s excited about implementing a nature-based curriculum and teaching her students in the school’s garden. An outdoor seating area for children, surrounded by trees, is visible from her classroom.

She’s stressed, however, about finding enough time to plan engaging lessons and making sure she’s providing enough support for students with disabilities.

Around noon, Bizon took a break from the moving and hammering and cleaning to eat her packed lunch, a premade salad with a packet of tuna.

As she ate, she acknowledged that it’s a big year for Chicago Public Schools outside Room 114’s walls. The city is holding its first school board election and contract talks are becoming increasingly tense between the Chicago Teachers Union and CPS. But after teaching through a pandemic and experiencing multiple teachers strikes, she’s not nervous about what this year will bring.

Every school year in recent memory feels “wild,” she said. “I’ve come to accept that it’s going to be a little chaotic.”

Shortly after Bizon finished her lunch, as if to prove her point, news broke that Mayor Brandon Johnson was considering replacing CPS CEO Pedro Martinez. But she hadn’t yet seen the reports. She had gone back to moving bookshelves.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org .