A week after their teacher left, the students were growing restless.

Despite promises that a permanent new teacher was coming, students in the sophomore-level chemistry class at Roberto Clemente Community Academy were sitting in their classroom with little to do. Though a substitute teacher was assigned to the room, the students quickly concluded that he didn’t know much about chemistry.

Carolina Carchi was struck by the reaction of one of her classmates: “They forgot about us.”

“When I heard that, this spark and passion grew in me,” Carolina said. She told herself: “No, you’re not going to be left out, they didn’t forget about you, and I’m going to be here to prove that.”

The following day, the 15-year-old got up in front of the class and began to teach her peers about the properties of liquids and solids and how to balance chemical equations.

Carolina went on to teach the class for two months during the winter of her sophomore year. A permanent teacher didn’t take over the classroom until the following fall.

When Clemente was built in the mid-1970s, the school was a symbol of hope in Humboldt Park and West Town, offering the promise of a new beginning for the Puerto Rican families who had settled in the area.

But now, 50 years later, Clemente students are missing critical instruction because so many teachers are regularly absent and positions go unfilled for long stretches.

Clemente is emblematic of a broader problem: CPS schools — and many other public schools across the country — are hamstrung by funding constraints and a nationwide teacher shortage, education experts said.

“It’s a resource issue that’s much larger than Chicago, much larger than the state,” said Erika Méndez, director of P-12 education policy for Latino Policy Forum, a state advocacy organization. “We have some big gaps to meet in terms of school funding. We are in a really tough financial time, and that’s coming with some big costs.”

But Clemente’s challenges are compounded by the management and leadership approach of administrators, teachers told Block Club Chicago.

As they deal with the stresses of working with students with significant needs, teachers say they’re not getting support from the school’s principal, which has left them burnt out and demoralized — and often absent.

At Clemente, about 46% of the teaching staff had more than 10 absences in 2023, according to CPS data. That means nearly half of Clemente teachers missed the equivalent of at least two weeks of school.

Yet CPS officials insist Clemente doesn’t have staffing issues.

The result is dozens of students sitting in what one teacher described as “dead classrooms” — unadorned spaces without permanent teachers where students receive little if any instruction and can essentially do whatever they want, according to interviews with teachers, support staff, and students.

Teacher absences

Last year was stressful for Betsy Garcia, one of Clemente’s school clerks.

Every morning, she checked her phone to find out how many teachers were absent that day. It was typically a high number — sometimes as many as 20, about a third of the school’s teaching staff.

Garcia frantically called in substitute teachers, but sometimes she and other support staff had to watch over a class or two because no one else could do it.

“We’re not teachers, but we have to do what we have to do,” Garcia said during a Local School Council meeting in May.

Across the district, teacher attendance hit a five-year low last year, according to state data reviewed by Block Club. About 43% of CPS teachers had 10 absences or more, the level the state considers “chronic” absenteeism that negatively impacts student achievement. The rate was even higher at Clemente.

On top of teacher absenteeism, 9% of Clemente’s staff positions were vacant as of last October, more than double the district average of 4%, according to district figures.

Clemente has a regular roster of substitute teachers who fill the gaps when teachers miss work. The district pays subs more to teach at high-poverty schools like Clemente. But subs are no replacement for full-time teachers, school employees said.

“I definitely have students who have [substitute teachers] for 3-4 classes easily everyday — that’s half their schedule. There’s a profound lack of instruction happening,” said one teacher who asked not to be named. “It affects school culture. … You have a lot more students cutting class or disorderly hallways because there’s less staff, less relationships.”

And sometimes the school doesn’t even have enough subs, leaving Garcia and other school employees scrambling to cover classes.

The result: Students are falling behind academically. SAT scores have dropped in recent years, according to state data, though learning disruptions at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic could be a factor.

“Our kids are coming to school to learn, but they just sit and watch movies or wander the halls,” said Dennis Acosta, Spanish teacher and member of the LSC.

A troubled history

Many in Humboldt Park were hopeful when Clemente opened in 1974 after years of issues at Clemente’s predecessor, Tuley High School.

“You had a school system that literally wasn’t listening to communities,” said José López, a longtime Humboldt Park activist. “In the ‘60s and ‘70s, CPS schools were considered some of the worst in the United States, and there was no attempt to address major issues of language support, trauma.”

López and other Humboldt Park leaders were instrumental in getting Chicago Public Schools leaders to open Clemente as a community-based school. It felt to them like Puerto Rican families would finally get the school they deserved, López said.

“What happened almost immediately was the total opposite,” López said.

Poverty and disinvestment in Humboldt Park and West Town led to gang violence around the school. The school also suffered from overcrowding.

The trouble continued in the mid-1990s, when a front-page Sun-Times story alleged school leaders used state anti-poverty funding to indoctrinate students into a Puerto Rican liberation group called FALN. Though investigators weren’t able to find concrete evidence of fraud, officials put the school on financial probation and then-district chief Paul Vallas replaced the principal.

Since then, school leaders have carried out a number of reforms, including some that the district turned into citywide initiatives like launching a satellite program for at-risk students and hiring parents as tutors and office help.

The Puerto Rican Cultural Center made Clemente the centerpiece of its “Community as a Campus” initiative. Under the program, Clemente regularly hosts practices for feeder elementary schools’ sports teams and offers tech training and financial literacy classes for parents, said López, the executive director of the cultural center.

In addition, Clemente became an International Baccalaureate school in 2015, meaning it offers a range of college-level courses, and its graduation rate and student attendance have improved over the last two decades.

“There’s a history of Clemente that is not a good history. Yet over the years, we’ve done everything possible to make sure Clemente would maintain itself as a school of choice for the young people in the community,” López said.

But as selective-enrollment and charter schools have become more popular, and as Humboldt Park and West Town have gentrified, Clemente’s student population has steadily dropped, which has led to fewer resources under the district’s system of student-based budgeting.

The school has capacity for 2,000 students, but today enrolls about 750, according to the district. About 200 of those students are migrant kids who enrolled last year after the district made Clemente a “welcome center” for families arriving from Central and South America, according to teachers.

The school is 70% Hispanic and 25% Black. Most students — 86% — are low-income, according to district data. Last year, about 28% of Clemente students were getting special education services, nearly double the district’s rate of 15%, according to state data.

Juanita Garcia, parent and chair of the LSC, said the counselor at her son’s Wicker Park elementary school discouraged her from sending him to Clemente.

“She said the [International Baccalaureate] program at Clemente wasn’t fully developed,” Juanita Garcia said. “If she had that conversation with me, I’m sure she had it with other people.”

Teacher turnover

In addition to the day-to-day absences, Clemente has struggled with teacher turnover.

Clemente had 57 teachers in the 2019-20 school year, a total that includes special education teachers and military instructors. But by the 2023-24 school year, less than half of those teachers — 23 — were still at the school, according to a Block Club analysis of CPS data.

Teachers and other school employees who spoke to Block Club said several teachers have left, gone on leave, or considered quitting because the school’s principal rarely provides support and often ignores requests for help.

Teachers said they’re instructed by administrators to give students a passing grade even if they do very little work.

“The principal does not support teachers in any capacity,” one employee said. “Copiers rarely have paper, classroom resources are not ordered, textbook requests are denied, and we are forced to give inflated grades. Students know the game.”

District officials contend Clemente doesn’t have staffing issues.

Clemente’s teacher retention rate — the year-over-year percentage of teachers returning to work at the school — has been “relatively stable” in recent years, though lower than the district average, officials said in an emailed statement.

But students aren’t learning core subjects like chemistry, algebra and Spanish for months, sometimes a full year, because full-time teachers aren’t in classrooms, according to teachers, employees, and students interviewed by Block Club. Teacher morale is the lowest it’s been in years, signaling more problems to come, the teachers said.

These issues aren’t unique to Clemente.

As it pushes for a new teachers contract, the Chicago Teachers Union last week launched a school vacancy tracker to illustrate “an alarming level of understaffing” in CPS schools. Some schools have 7-10 teacher vacancies. Union leaders said it’s the result of “the district’s lack of a plan to fully fund our schools.”

All CPS schools have felt the impact of a nationwide teacher shortage, which has gotten worse since the COVID-19 pandemic, said Ben Felton, the district’s chief talent officer. But Felton said the district is “trying to get away from post and pray” by extending early job offers and expanding residency programs to attract more teachers.

While some schools have openings, Felton said overall the district has 2,500 more than it did five years ago.

To bring down chronic absenteeism, the district is trying to connect teachers with more wellness programs and mental health resources, while also backing up principals who need to discipline employees for excessive absences, CPS officials said in a statement.

‘No one … to teach me’

Yet many Clemente students have stories of going long stretches without permanent teachers.

Mya Maldonado-Bustamante loves being in the classroom and is eager to learn.

But last school year was frustrating for the 16-year-old. Mya didn’t have full-time teachers for math and chemistry, which meant she usually spent a couple hours of her school day sitting around, without much school work to do. Now she doesn’t feel prepared for junior year.

“It was just really challenging because I love math, but no one was really there to teach me about it,” Mya said.

Similarly, 15-year-old Annaliz Stovall went without math, English, and Spanish teachers for long stretches of last year. She spent part of her summer trying to learn Spanish on her own.

“They expect us to take Spanish II next year and pass. It really upset me,” Annaliz said. “I care a lot about my grades, but I don’t know anything. I obviously can’t excel at it.”

Mya and Annaliz consistently show up to school and have no plans to transfer out, but the instability has led dozens of students to leave the school or not show up, according to interviews and state data.

Last year, Clemente’s student mobility rate — the percentage of students who transferred either in or out of the school — was 27%, nearly triple the district-wide rate of 10%, according to state data.

High student mobility, along with chronic truancy and low student attendance, are common issues at schools like Clemente that serve mostly low-income students. But students are feeling the impact of teacher absences, according to interviews with teachers and other school employees.

“Today a student came up to me and confided [in me]: “All day everyday at this school I do nothing,” a school employee said during the last school year.

‘It starts at the top’

A number of teachers at Clemente say Principal Devon Morales has made the staffing issues worse.

Morales became Clemente’s principal in 2022. Since then, his leadership style has created a culture of fear and retaliation, pushing some teachers out of the school, current and former teachers told Block Club. They said Morales is cozy with his allies at the school, a group made up of longtime employees and friends, but shuts out teachers and other employees who question him.

Teachers who have decried his leadership have struggled to get new supplies and approvals for time off, they said.

Morales didn’t notify teachers that there was a shooting outside of the school at the end of last year — one example of his “lack of communication about anything that’s important,” one teacher said.

Another employee said Morales’ administration turns a blind eye to the school’s challenges and fails to discipline students for serious misconduct, like threatening a teacher.

“The kids don’t want to be there, the teachers don’t want to be there, and it starts at the top,” the employee said.

Almost all of the teachers interviewed by Block Club spoke on the condition they not be named because they’re worried about retaliation, even if they’re no longer employed at the school.

Despite Block Club’s repeated requests over two months, Morales wouldn’t make himself available for an interview for this story. District officials didn’t respond to questions about Morales’ leadership.

Though they’re troubled by the principal, many teachers, staff, and parents have poured energy into the school and want to see students succeed. School employees and community leaders are fiercely protective of Clemente; many were apprehensive about participating in this story for fear it would cast a negative light on the school.

Student becomes the teacher

Carolina grew up in nearby West Humboldt Park and felt a moral responsibility to go to Clemente instead of one of the city’s selective-enrollment high schools, she said.

When her algebra teacher left during her freshman year, Carolina started to teach the class herself.

“No students at Clemente are ever in an unsupervised classroom and substitute teachers have access to any lesson plans they may need on any given day,” district officials said in a statement.

But the substitute teacher assigned to Carolina’s class didn’t know algebra and let her take over, according to interviews with students and school employees.

“I took it as a good journey and challenge to simply just do something for my class, and not leave them behind,” she said.

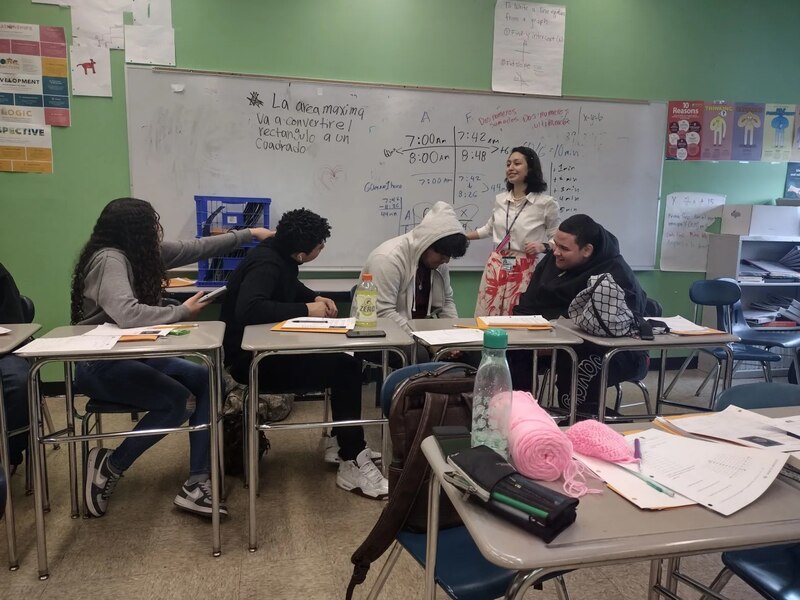

The same thing happened in her chemistry class the next year. Carolina prepared lesson plans during her free periods and went to FedEx after school to print out assignments. She brought in a bag full of extra pencils and other supplies, including a plasma ball, for students to use while she taught.

“My classmates are more visual learners,” she said.

Sabrina Negròn, one of Carolina’s classmates, said she and other students struggled with the state science exam after going without a certified teacher, but Carolina “got us as far as she could knowing what she knew.”

“I think she’s an amazing person for what she did because she didn’t need to,” Sabrina said.

Carolina, now a senior, said she was simply following her passion for Clemente.

“I strongly believe in community schools, and that they should be an anchor in their communities,” Carolina said. “A school with the proper resources can be just as successful as any other school.”