Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

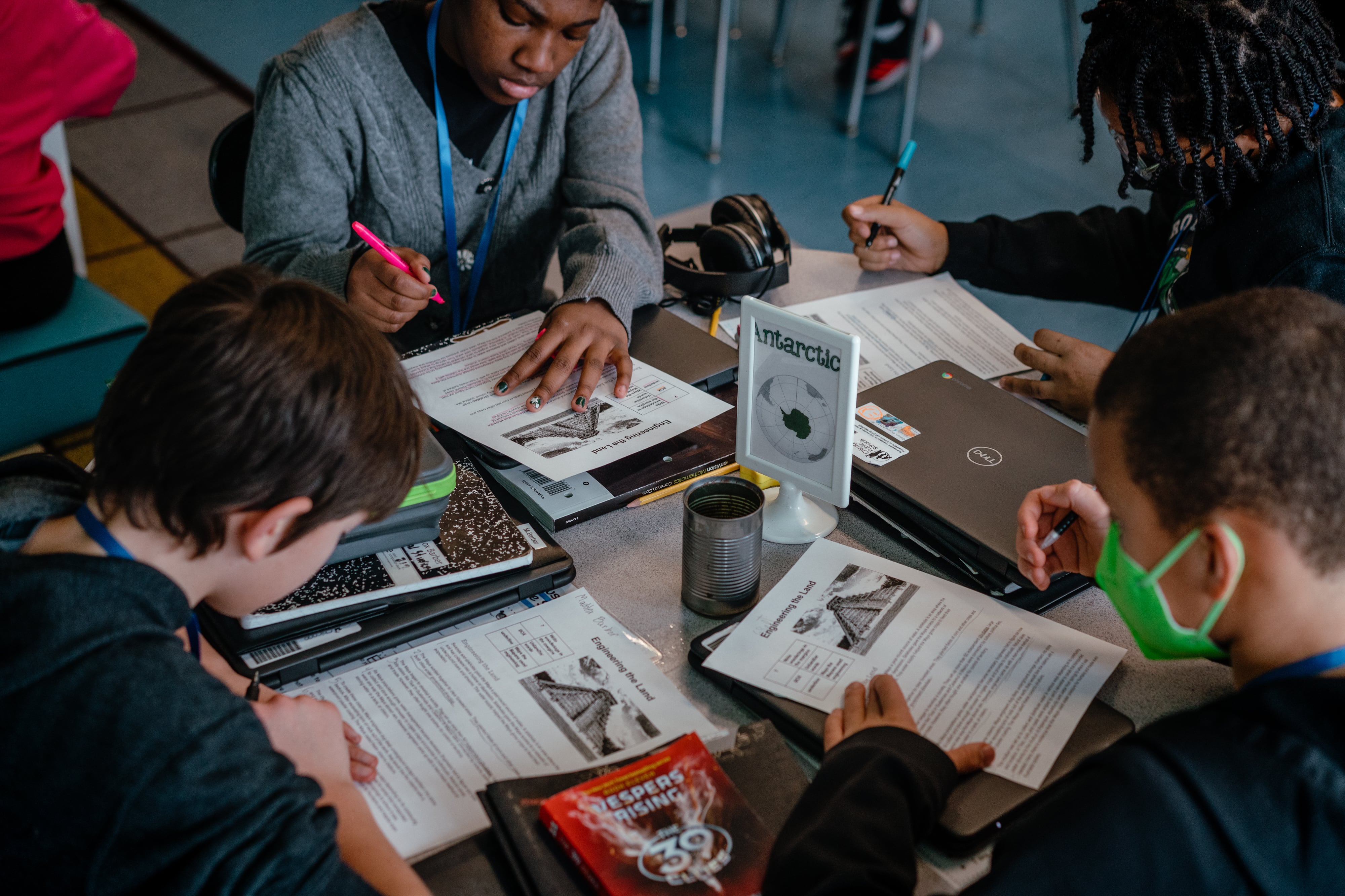

The Chicago Board of Education oversees policies that can impact how schools teach the district’s 323,000 students, and ultimately, how well students learn and prepare for adulthood.

By most accounts, the district has come a long way in the three decades since former U.S. Secretary of Education William Bennett infamously called Chicago’s public schools the worst in the nation.

Since then — and after multiple efforts at reforming public education — performance in Chicago Public Schools has significantly improved, according to researchers and public data. Researchers have also found that Chicago’s students have more recently shown some of the highest growth in reading since the pandemic compared to other big school districts.

But there is still vast room for improvement. While a majority of high schoolers graduate on time, most CPS students don’t meet certain reading and math standards.

Chicago is home to some of the best schools in the state and country, and also some of the worst, by state measures.

Illinois labels all schools with one of five performance designations — Exemplary, Commendable, Comprehensive, Targeted, and Intensive. The top 10% of schools based on a variety of metrics are deemed Exemplary, while the lowest 5% are labeled as needing Intensive Support.

Elected school board members will represent schools with varying performance levels.

These ratings are a combination of dozens of different metrics aimed at measuring student success, including test scores, graduation rates, and attendance.

In the 2022-23 school year, just over a quarter of CPS students in grades 3-8 met or exceeded reading standards on the Illinois Assessment of Readiness, and another 17.5% passed math, according to the most recent state data. Eighty-four percent of high schoolers graduated on time last year, while the dropout rate was 9.4%.

Other measures, such as student attendance, can provide clues on the challenges kids face. Nearly 40% of Chicago Public Schools students were chronically absent in the 2022-23 school year, according to the most recent state data — meaning they missed at least 10 days of school.

These figures provide a fuller picture when you look at how they’ve changed over time and how they look for different groups of students.

CPS students are catching up on reading, math post-pandemic

Most of Chicago’s students are not meeting state standards in reading, math, and science.

A quarter of students were considered proficient in reading, close to 18% in math, and roughly 37% in science, according to a state measure that calculates pass rates of several standardized exams given to students in elementary grades and high school. Statewide averages were higher in all subjects: Just over one-third of Illinois students passed reading, nearly 27% passed math, and just over half passed science.

None of these assessments are created by CPS and can’t be controlled or changed by the school board. However, the board can use assessment data to make decisions that impact kids, such as hiring additional tutors at schools or requiring certain curriculum be adopted.

Reading and math state test scores for children in grades 3-8 dropped after the pandemic and still lag behind 2019 levels. Last school year, reading scores were about 1 percentage point behind those in 2019, and math scores were more than six percentage points behind.

But those scores have gradually climbed since kids re-entered school buildings in 2021. A recent study from Stanford and Harvard universities found that Chicago’s reading scores have bounced back from the pandemic at a greater rate than most big school districts.

There are stubborn racial disparities in test scores. Roughly half of white and Asian American students in grades 3-8 passed reading and math tests last school year – at least double the share of their Hispanic and Black peers.

Students in low-income households, those learning English as a new language, and those with disabilities also score far below students citywide.

As part of the new state law that establishes Chicago’s elected school board, board members must also launch a special committee that looks at how to improve academic achievement for Black students. The school board also has a new Special Education Advisory Committee that meets semi-regularly.

Similar outcomes — and disparities — exist at the high school level.

All Illinois juniors have taken the SAT as the required state achievement test since 2016, but will be required to take the ACT starting this spring. In CPS, nearly 19,900 high school students took the SAT last school year. They scored an average composite score of 933, roughly 120 points below the national average. The district’s performance on the SAT has been dropping.

Twenty-two percent of those students met or exceeded SAT reading standards – nearly four percentage points less than before the pandemic and close to 10 points below statewide averages, according to state data. Another 19% met or exceeded SAT math standards – seven points below 2019 scores and close to eight points below scores across the state last year, according to state data.

White, Asian American, and multiracial students meet SAT reading and math standards at higher rates than their Black and Hispanic peers.

Many schools have tried different strategies at improving math instruction. And the district used a chunk of its federal COVID relief funds to staff schools with academic interventionists, who are tapped to work with struggling students.

Chicago’s graduation, college enrollment rates are on the rise

Chicago’s graduation rate has been rising for the better part of the past decade, dipping once after the pandemic. That mirrors national trends of rising graduation rates. Seventy-seven percent of CPS students graduated on time in 2017; that figure grew by seven percentage points by 2023.

The board has the power to tweak or change policies that can impact graduation rates, such as what courses and how many credits are required to earn a diploma. It can also impact how graduation rates are calculated and have the power to create programs, such as credit recovery and alternative schools to improve students’ chance of graduating.

For example, former Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s appointed school board opened dozens of new alternative school programs, some of them half-day, online programs, to allow students behind on credits to catch up and earn a diploma. By 2021, about 1 in 10 high schoolers attended alternative schools.

As with test scores, racial disparities persist among students who graduate on time. Black students have been the least likely to graduate on time, with a graduation rate four percentage points behind the citywide average in 2023. Hispanic students graduated at a rate just above the citywide average. White and Asian American students surpassed the average.

The dropout rate dipped between 2017 to 2021, from nearly 14% to 8%, but has recently been on the rise.

A University of Chicago study found that more students are pursuing higher education, bucking national trends that show sagging college enrollment. Nearly 61% of CPS students who graduated in 2022 immediately enrolled in college. But racial disparities also exist within this data: While 80% of white women immediately enrolled in college, only 45% of Black men did the same.

Troubling absenteeism rates in Chicago Public Schools followed the pandemic

Tracking attendance and chronic absenteeism can illustrate how often students are actually attending school and learning, and can help the public understand why students might be falling behind in subjects.

In 2023, just over 88% of CPS students attended school regularly, compared to 91% statewide. But that rate has worsened in recent years: For the decade before 2021, when rates started slipping, the attendance rate hovered between 92-93%.

Chronic absenteeism has grown, showing that students have struggled since the pandemic to reestablish the daily routines that get them into class every morning.

In 2018, 23% of CPS students were chronically absent, state data show. That rate grew to nearly 45% in 2022 – a trend seen in other big districts. Students appeared to have attended school more regularly last year, when the chronic absenteeism rate dipped to about 40%, but that was still nearly double the rate just five years earlier.

The district has attempted to improve attendance by having schools reach out to families more often and investing more in things that might support students when they make it to school, such as mental health services and staff who are meant to resolve conflicts among students without resorting to punitive disciplinary practices.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.