This story was originally published by the Illinois Answers Project.

Among Chicago Public School employees, no one has been a bigger cheerleader for an invention designed to reduce dangerous amounts of lead in water from school drinking fountains than top administrator Robert Christlieb.

Christlieb, the district’s executive director of facilities, operations and maintenance, has worked for at least seven years on the problem of lead in drinking water at CPS schools, a critical issue for student health.

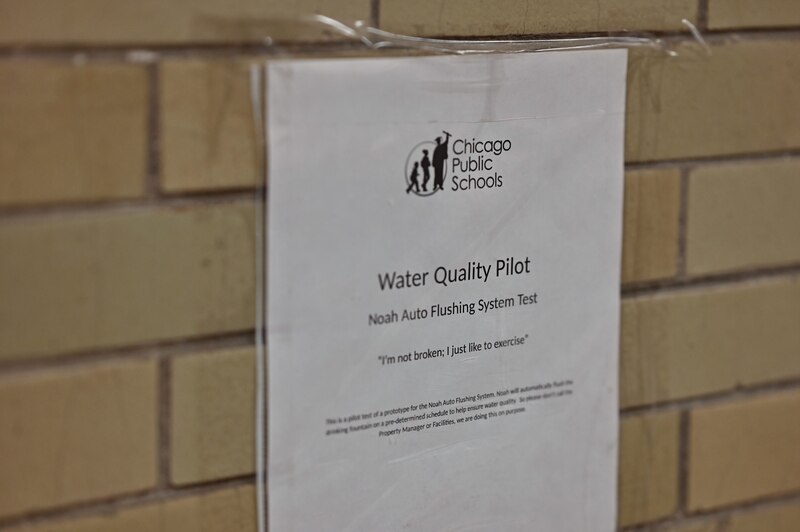

He’s appeared on panel discussions, in news articles and podcasts to highlight the district’s strategies, which has included installing an invention called Noah — a device that automatically flushes student drinking fountains on a set schedule to reduce the build up of lead in stagnant water. Christlieb has touted the device as a cheaper solution than doing extensive plumbing work in hundreds of aging school buildings.

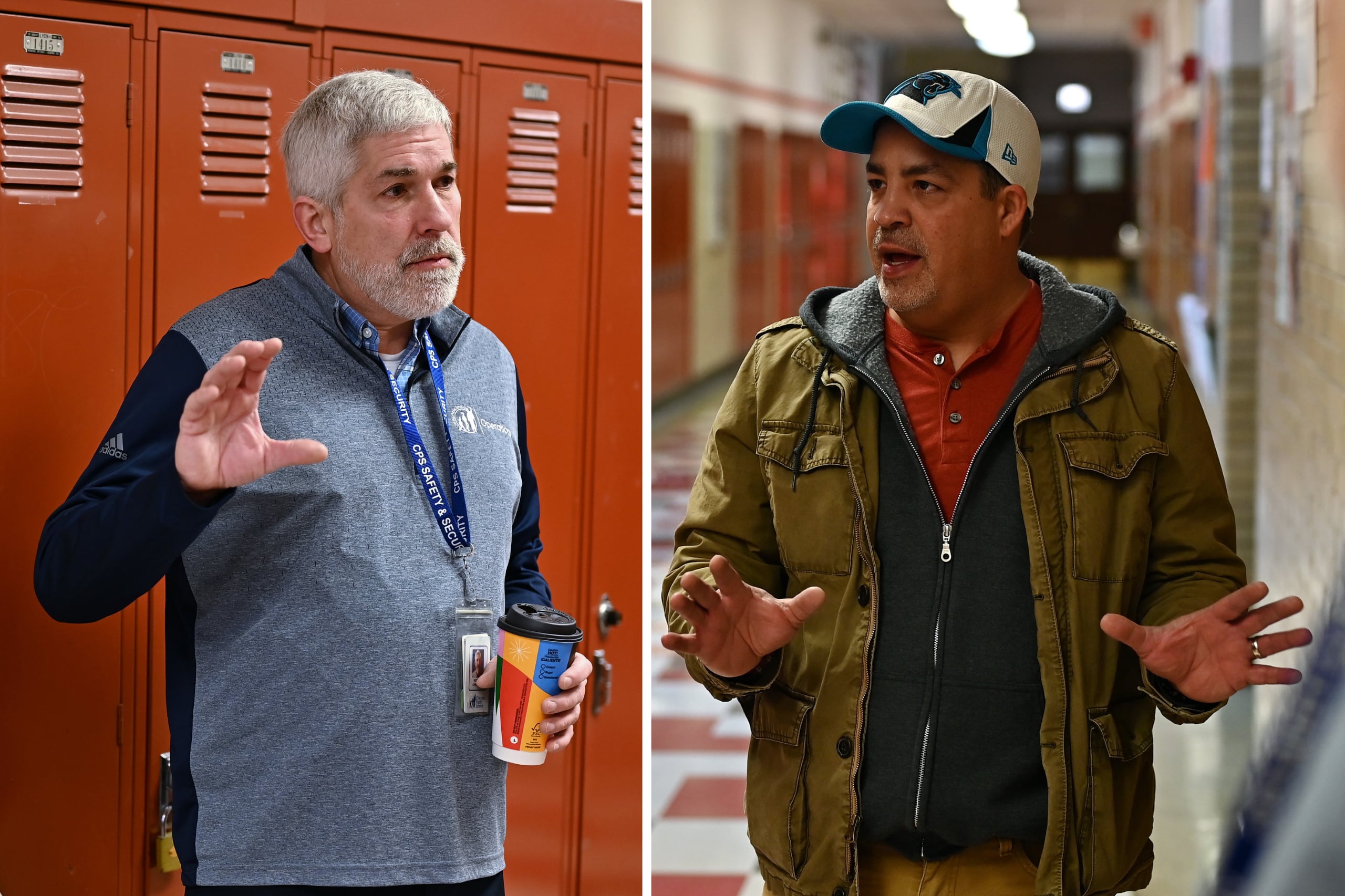

In public, Christlieb says Michael Ramos, who works for a CPS contractor as the chief building engineer at Von Steuben High School on the Northwest Side, is the inventor of Noah. Christlieb tells the story of how Ramos wanted to protect his students from lead and worked to create a low-cost, reliable device to do just that.

“Michael [Ramos] has solved the lead problem in public schools, not just in Chicago,” Christlieb was quoted as saying in a 2019 Seattle Times article,. He added in the story that the district had approved expanding Noah to 25 schools as part of a pilot program. But the expansion never happened, “due to resources, staffing and the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to CPS. For now, the Noah device is in five CPS schools — three high schools and two elementary.

Christlieb, who makes more than $170,000 a year at CPS, neglects to mention one key detail as he tells the story of the device’s creation.

He’s more than just a fan of Noah. He’s listed as the co-inventor of the device he’s been promoting for years. Christlieb and Ramos share the U.S. patent for the Noah device, federal records show.

Nor does he mention that he once formed a business with Ramos to sell the device — a business that has since dissolved.

CPS declined to make any school official available to Illinois Answers Project reporters to discuss the district’s actions. CPS repeatedly did not address questions regarding whether Christlieb violated any of its conflict of interest policies but stands by him continuing to promote autoflushing, despite him having a patent on the Noah device. CPS said Christlieb does not supervise Ramos or oversee the contract with the CPS contractor that employs him.

The district explicitly prohibits its employees from working as a vendor and doing business with the school system. Christlieb formed a company with one of his friends and Ramos in March of 2017 called RCS Water Quality Solutions to sell Noah. RCS listed as its corporate address a residence Christlieb owns in Wisconsin.

In the fall of 2017, CPS says it learned of the partnership and told Christlieb that he could not continue to work at CPS if he didn’t divest.

On the same day that Christlieb dissolved RCS, he completed paperwork to create a new business called Lead Out Manufacturing and listed Ramos as the registered agent. He again used his residence in Wisconsin as corporate headquarters, corporate filings show.

CPS said in a statement that Christlieb “volunteered” his time to help Ramos fill out the administrative paperwork to set up Lead Out and allowed Ramos to use his Wisconsin address but has nothing to do with the company.

CPS said it has no evidence that Christlieb ever profited from the Noah devices. Christlieb wrote in answers to questions that he did not make a profit, and Ramos, in an interview, agreed that Christlieb never made any money from them. Both men indicated that they had been interviewed by the CPS inspector general’s office regarding their ties to Noah, and no action was taken against them.

“Mr. Christlieb helped develop a product that helps remove lead from drinking water and kept his name on the patent as a matter of intellectual property,” CPS said in a statement.

Christlieb used CPS testing data to support the patent for the Noah device as well as for a white paper designed to promote autoflushing at Orr High School, where Noah had been installed. When asked whether Christlieb’s use of the testing data for personal use violated CPS policy, the district noted that water testing data can be obtained by anyone through a public information request.

Despite Christlieb’s significant role in the school water testing, CPS argued that the fact that he has a patent on the Noah device did not compromise its water testing.

The district said in a statement: “CPS implements a proactive lead testing program that goes above and beyond any state requirements and uses the best known practices for testing and preventing lead build up in drinking water. A flusher system ... is in a handful of our more than 600 schools and we stand by our district’s proactive practices and testing procedures. The district’s lead mitigation program is overseen by a team of professionals in our facilities department. Mr. Christlieb’s invention of one tool in this field — and that tool’s use in a small fraction of the 600-plus schools in the district — has no impact on the quality or veracity of the district’s program to test for lead, mitigate lead in water and/or repair/resolve for lead in water.”

Conflicting stories

In separate interviews, the two men, once partners in selling the device, disagree on basic facts about who invented the device, what money they contributed to get it patented and what roles they played in the business, called Lead Out Manufacturing. Christlieb has offered varying accounts of his role in the firm, from initially writing in response to questions from reporters that he had 49 percent ownership of Lead Out, to saying in a CPS statement that he divested from the company soon after it was created, to indicating, in a final CPS statement, that he was never an investor at all. Ramos, in an interview, said Christlieb was involved for “a couple years” in Lead Out.

In an interview, Ramos said he is the sole inventor of Noah and he put Christlieb on the patent to persuade Christlieb to become a partner with him. Ramos noted that Christlieb as a high-ranking CPS official had “a big reach” and having him as part of the company could help sales of the device to other school districts. He said that they weren’t “necessarily” going to go after CPS business.

“His name does appear on the patent, but that doesn’t mean that he had anything to do with the invention,” Ramos said in an interview with Illinois Answers reporters earlier this year.

Ramos said initially after they met in 2016 both men “were basically planning on starting a partnership to take it to New York, New Jersey, and do all these other things, you know, because Rob has a big reach. And I felt like, wow, what a better partner than having Rob, you know, so … as a sign of like, good faith to, like, try to bring him in and say, Rob, you know, I’ll put you on a patent with me.”

“I’m trying to introduce this to districts,” Ramos said. “The schools need it. I figured this is something that’s affordable, the districts could use. Why wouldn’t I reach out to someone like Rob, who has the title, who has the name and has the respect in the industry?”

Earlier this year, Houston Public Schools found elevated lead levels within some school buildings, prompting Ramos to text Christlieb.

“Good morning Rob, this is another candidate for Noah. Is there any way you can reach out to them? I can reach out, but they usually don’t respond because i seem to come across as selling snake oil. If it comes from you, they will see it as valid.” Records provided by CPS do not include Christlieb’s response.

Ramos said the men worked together for a couple years trying to sell the device to school districts across the country but never realized much success. Ramos said he and Christlieb parted ways after he realized the arrangement could look suspect to CPS but argued the men never did anything wrong and that Christlieb never received any money from the company.

In an interview at Von Steuben High School in December last year, Christlieb credited Ramos with inventing the device and marveled at how Ramos was able to build what Christlieb could only think about. He talked about how just the month before he came out to Von Steuben High School, where Ramos worked, to see his Noah device, he had just been thinking the month before about such an invention.

“So the interesting thing was, before I came out here in October of 2016, to see what he had done. In September of 2016, I had sat down one night, and I sketched out the idea of doing a bypass filter and having some type of controller on it,” Christlieb said in the interview with Illinois Answers reporters. “And I’m like, ’Man if I could build something like this.’ But I didn’t have the skill set, right? And Michael did, and Michael must have been listening to me across the city because we didn’t know each other at that time and then all of a sudden I’m being called out here a month later and I’m like this is exactly what I was hoping for. But someone was actually able to put it together and the concept works and the mechanics work. It’s very simple ... Simplicity is key for us.”

After reporters discovered that Christlieb’s name was on the patent, they attempted to interview him at his Wisconsin address where he was staying. He declined to answer questions in person but responded to a set of written questions.

Christlieb wrote that he was on the patent because he had made substantial contributions to the invention of Noah. He did not answer follow-up questions that asked him to detail those contributions.

The men also disagree on other issues regarding the patent. Ramos said he paid all the legal fees for the patent work on the Noah device. Christlieb, though, said he contributed about $5,000 for the legal work. The patent was granted to Ramos and Christlieb in 2021.

CPS provided two documents that it said showed that Christlieb had nothing to do with Lead Out. One is a the most recent Wisconsin corporate filing that shows Ramos is the registered agent for the firm, but while Christlieb’s name is not on the document, it does not address ownership. The document lists Lead Out’s corporate address as Christlieb’s Wisconsin address.

The other document provided by CPS and Christlieb involves him assigning his rights to the patent on the Noah device to Lead Out. The document is dated June 2018, more than six months after Lead Out was formed. The document is signed by Christlieb, but not by Ramos, and once again lists Christlieb’s Wisconsin address as Lead Out’s corporate address.

Starting with Flint

The district began focusing on assessing its drinking water in 2016 after the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, and began a 10-year testing program by sampling its over 12,000 water fixtures for lead levels.

In the first year of testing, 60% of the 490 schools tested returned at least one sample with a lead level over 5 parts per billion, exceeding the state’s action level for lead in water. Last year, the district tested 174 schools, and 92, or 53%, had at least one sample exceeding the state limit.

Since replacing all lead pipes could cost up to $2.5 billion, according to district estimates, CPS first focused on limiting the stagnant water in pipes, where lead collects, by having building engineers manually flush all drinking water faucets in its 528 campuses. Building engineers, tasked with maintaining the HVAC, electrical and plumbing systems, are required by district protocols to flush schools after a “period of nonattendance,” such as a weekend or break, once a week.

At a campus like Von Steuben, where Ramos works, manual flushing would require him and his team of two engineers to individually run the water on all 42 fixtures in the school for 3 minutes before students arrive on Monday or after a long break, Ramos said. Additionally, they would still need to complete other responsibilities such as preventative maintenance and repairs before students arrive. Experts say that while flushing can decrease lead levels, the manual process doesn’t guarantee water is safe to drink because it’s prone to human error. The district employs 685 engineers who oversee 800 buildings, meaning some engineers cover multiple schools.

Christlieb and Ramos argue that Noah works well because the device automatically flushes the water fountains and doesn’t rely on employees to do it.

In addition to Von Steuben, the devices have been added to drinking fountains in CPS schools at Orr High School, Belding Elementary, Onahan Elementary and Kelvyn Park High School.

All the devices installed at CPS schools have been donated by Ramos or purchased by local school councils. There are no records showing that CPS has cut a check to Lead Out Manufacturing, but in some instances, CPS paid a contractor to install the devices. The devices cost about $395.

The devices also have been installed at two suburban school districts — Crete-Monee School District and Indian Springs School District 109, according to documents obtained by Illinois Answers.

Years of promoting autoflushing — and Noah

Christlieb has promoted the Noah device for years, at times using CPS resources, starting as early as July 2017.

In that month, Christlieb drafted a case study about the Noah flushing system at Orr Academy. And Christlieb shared the Orr case study widely to multiple school districts and city governments using his CPS email account.

In March of 2019, he appeared in a Chicago Health Magazine article that promoted autoflushing and appeared in a photo with Ramos in the story.

In a podcast interview, Christlieb said he installed Noah in his own home and that it worked “perfectly.”

And as recently as May of this year, Christlieb, using his CPS title, appeared with Ramos as a guest speaker at a Noah-hosted seminar for Chicago Water Week, in which he discussed the Orr High School pilot program and Noah’s benefit to the district.

CPS emails and text messages show that Christlieb and Ramos also talked during the workday about promoting Noah to schools in Chicago such as City Colleges and outside Illinois including Philadelphia Public Schools and New York City Public Schools.

Christlieb appears to have played a role in efforts at establishing Noah’s credibility as an effective solution.

In March of 2021, Christlieb emailed the white paper he wrote on Noah’s use at Orr as well hundreds of pages of testing data to a Philadelphia school official, who was interested in the invention and who thanked him for his time “explaining the benefits of your Noah system.”

Christlieb responded to the official by telling him who else at CPS was involved in the project.

“For Noah,” Christlieb added, “I would recommend talking with Michael Ramos.”

Cam Rodriguez is a former data reporter for the Illinois Answers Project, now serving a fellowship at The New York Times. Jewél Jackson covers education for Illinois Answers.