Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

Before the start of this school year, 18-year-old Odeth Garcia, a senior at Hancock College Prep on Chicago’s Southwest Side, did not know that her first time voting would include casting a ballot for the people charged with ensuring she gets a good education.

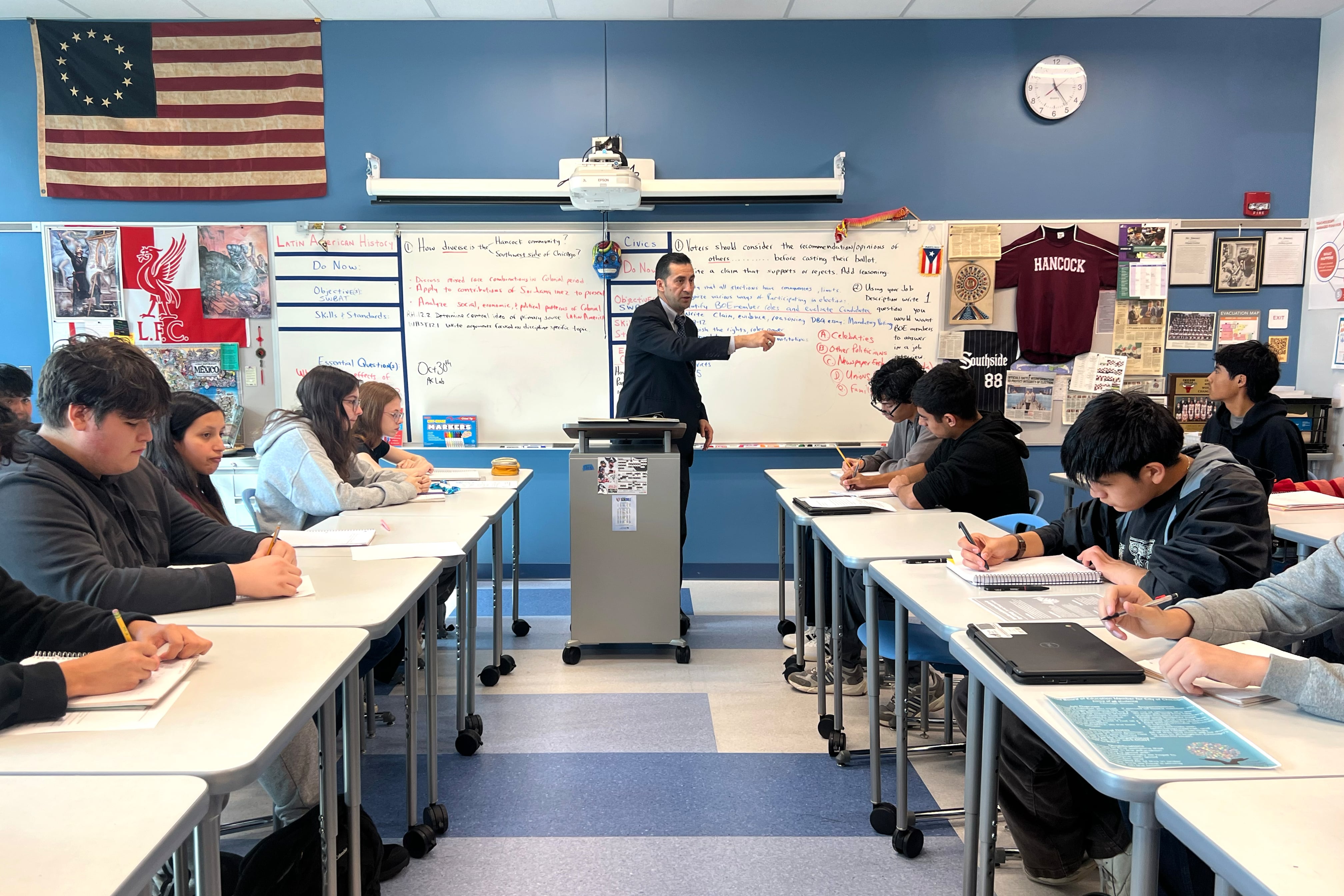

Inside Room 105, Odeth and 20 of her peers dug into the day’s civics lesson: Chicago’s historic school board elections. They would learn that the board has immense power, including to change school policies and curriculum and adopt the district’s budget.

“I feel like the fact that they’re being elected in the first place is really cool, because I feel like we should have a say in deciding, like, how we’re going to learn,” she said. “It was interesting to learn how much they actually control.”

Teacher Froy Jimenez teaches an elections unit every year, but 2024 presented a new opportunity. In addition to learning about the race for president and other local races, Odeth learned the city would elect 10 school board members, while another 11 would be appointed by the mayor.

Jimenez ran for 11th Ward alderman in 2023, serves on Hancock’s Local School Council, and is on the district’s citywide Local School Advisory Council. But building a lesson around the new school board elections was not solely driven by his own interest in politics.

He said he used resources curated centrally by Chicago Public Schools that were meant to help teachers teach about the upcoming school board elections. Jimenez went to an optional professional development session to learn and found the lessons useful.

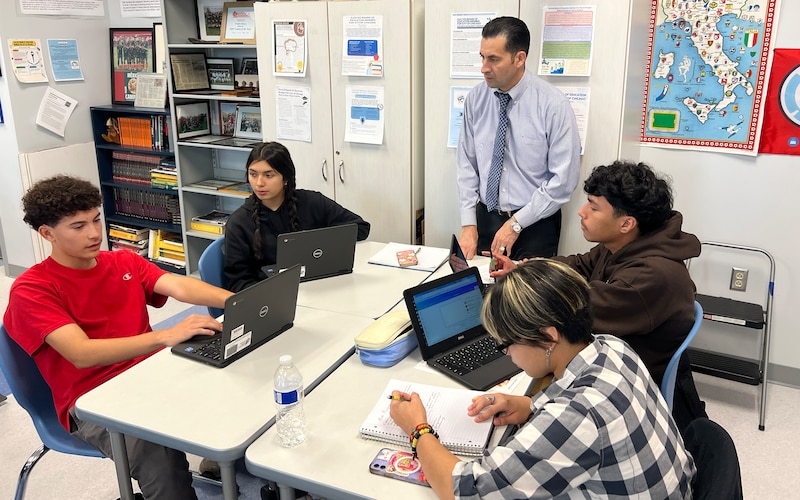

For his class, Jimenez wanted students to understand the responsibilities of being a school board member, but he said he wanted to take the lessons “a step further.”

“That step further was them coming up with their own version of what it means to be a board member,” Jimenez said.

Students learn to do their own research

Students pulled out a previous homework assignment: job descriptions they created for the school board in the form of colorful fliers that advertised the school board positions and included qualifications for the job. The class rotated around the room, viewing peers’ job descriptions and writing interview questions they’d pose for candidates.

“How would you distribute 10 bil?” Odeth wrote, referencing how a candidate would want to spend the district’s nearly $10 billion budget.

The lessons are about more than just this election. Jimenez said it’s also an opportunity to teach students how to find reliable information, come to their own conclusions, and understand that the outcome can impact their daily classroom experience.

“It’s important not only to vote, but it’s important to be an informed voter, and you have to do your own research — that’s something that I think we’ve emphasized,” Jimenez said.

On a cloudy October Tuesday, Jimenez asked the kids to consider the following statement: Voters should consider others’ opinions – such as celebrities or influential organizations – when casting their ballots. He asked a student to tally up her peers’ opinions on the dry erase board. The student scribbled the words “refute” and “support” across the board.

One student said people should do their own research, a tally marked under “refute.” Another said others’ opinions can provide a helpful perspective, since the outcome of any election impacts everybody. That was tallied under the “support” column.

There wasn’t a right answer. But the lesson was meant to get the students to think critically about how they’re reaching conclusions about candidates, Jimenez said.

Some students are preparing to vote for the first time

A handful of Jimenez’s students, like Odeth, are of voting age this year, he said. One of them is 18-year-old Luis Garcia, a senior at Hancock. Like Odeth, he didn’t know about Chicago’s first school board candidates until he took Jimenez’s class.

Luis said he knows where he stands politically. But in Jimenez’s class, he learned that “it’s good for me to learn about the other side.”

After reviewing the job duties of a school board member and learning how to find reliable information, the students rearranged their desks into groups to start one of their final projects for this unit: creating voter guides.

Jimenez tasked them with creating a few categories, such as qualifications, that they felt voters should know about each candidate. He provided multiple links to news websites that had created voter guides — including Chalkbeat’s with the Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ — as sources. He also encouraged students to visit candidates’ websites.

Jimenez occasionally asked the class questions that seemed targeted toward getting them to think critically or be aware of misinformation. As students prepared to work on their voter guides, he asked them about the difference between finding information on a candidate’s website and a news source.

“I think a neutral [website] would tell you about the good and the bad,” one student said.

On their own website, another student said, a candidate “would sugarcoat” their experiences.

As one group worked on their voter guides, students raised questions with each other about what counts as experience. Some of those critical thinking skills peeked through.

Junior Miche Avendano-Escobar, 17, asked: Would attending past board meetings count as experience or qualifications? Her classmate, fellow junior and 16-year-old Eduardo Hernandez Jr., decided it would fall under experience, because attending meetings makes them “familiar with the environment.”

Senior Isabella Garcia asked if they should include candidates’ GPAs in their voter guide, an idea that popped into her mind as she combed through District 4 candidate Kimberly Brown’s resume, which said she had a 3.9 GPA in graduate school.

As the group dove into candidate backgrounds, Miche chimed in as she reviewed District 2 candidate Maggie Cullerton Hooper’s website: “My god, this girl has so many experiences.”

As class wrapped up, Jimenez asked the students to write down on a small piece of paper what they think is the most important factor in choosing a candidate and why.

Before he walked out, Eduardo quickly scribbled his answer: Look at the candidate’s “main issue” because “it shows priority and headspace.”

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.