Data analysis by Kae Petrin

Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

When Illinois lawmakers carved up Chicago into 10 areas for the city’s first school board elections, one of the districts they created is a sprawling expanse that hugs the city’s south lakefront from Soldier Field to the Indiana border.

District 10 has bustling high-performing schools and shrinking campuses blocks apart. It has vacant buildings left behind from school closures and one of the highest average student poverty rates in the city. But it is also home to many of Chicago’s political and business movers-and-shakers, including former President Barack Obama.

The first candidates to declare their bids for Chicago’s new, partially elected 21-member board were in District 10.

Forty-seven Chicagoans — including 10 in District 10 alone — tried to run for school board. But just four made it on the ballot here: Robert Jones, a pastor supported by the Chicago Teachers Union who once joined a hunger strike to keep a local high school open; Karin Norington-Reaves, a nonprofit CEO and mother of a blind CPS student who had run for Congress and got backing from pro-school choice super PACs; Adam Parrot-Sheffer, a CPS parent, former district principal, and education consultant; and Che “Rhymefest” Smith, a self-funded Grammy Award-winning rapper and activist.

Over the following six months, what played out in District 10, in many ways, mirrored the dynamics and drama of the historic race across the city.

On one hand, the election was a joyful, uplifting exercise in representation — breaking with decades of mayoral appointments to a mostly rubber-stamp school board. On the other, the messiness of democracy was on full display, with reductive, misleading soundbites and big cash flowing into the races. It was tough for newcomer candidates without institutional backing or personal wealth to join the race, including the six people knocked off the ballot in District 10.

More than $9 million was spent on mailers, ads, and text messages praising or savaging the candidates, according to a Chalkbeat analysis of the latest campaign reporting. Still, many voters went into the ballot box on Election Day not knowing that the school board race was even happening.

As the new school board gears up to take over in January and set standards for a form of government new to Chicago, what are the lessons of the city’s first ever school board elections? And what, if anything, needs to be changed before voters pick school board members again in 2026?

‘A horrible way to do democracy’

In early September, nine weeks before the Nov. 5 election, Che “Rhymefest” Smith sat on the deserted upper level of the Subterranean, the Northwest Side music venue where he’d cut his teeth as a rapper back in the 1990s. He was checking in with his partner, Heather, and campaign manager, Sean Tenner, before a concert to drum up support and raise money for Smith’s school board bid. The Smiths and their music studio had already loaned the campaign nearly $100,000.

That evening, Smith, who unsuccessfully ran for alderman in 2011, felt frustrated with this latest foray into campaigning. He railed about “the transactional nature” of Chicago politics.

He wanted to talk about things like cracking down on wasteful district spending or striking partnerships with museums and nonprofits to boost arts education. But as he met with organizations whose endorsements hold sway with voters, they only seemed to care whether a candidate had a path to victory. His self-funded campaign seemed to be a turnoff; it made it harder to buy his loyalty, he suspected.

He was also still shaken by the experience of getting on the ballot.

First, would-be candidates had to secure 1,000 signatures — a threshold some elected school board advocates said was prohibitively high. In all, 47 overcame that hurdle. But then 27 of them ran up against a daunting and bewildering staple of Chicago’s elections: petition challenges.

The Chicago Teachers Union paid a set of election lawyers to represent people challenging petitions in 18 of the cases, including five in District 10. Smith and Norington-Reaves were among the candidates challenged by CTU proxies. The union also paid to fend off challenges to their endorsed candidates, including District 10’s Robert Jones.

Smith challenged other candidates too, including Jones. After a month of hearings and a review by handwriting experts, the two quietly agreed to drop their challenges against one another.

The last-minute truce rattled Norington-Reaves, who amassed more than 300 pages of voter affidavits and other evidence to counter three challenges. She fired off a furious press release, saying the race had been “marred by those who claim to support representative government but undermine it in the same breath.”

Smith was relieved he had made it. But he felt uneasy about the unsavory practice of trying to knock out the competition.

“It’s a really horrible way to do democracy,” Smith said in a September interview with Chalkbeat. “We all get caught up in a tangled web of the political process.”

But that night, Smith brightened as he headed downstairs to kick off the performance. In a black baseball hat, black-framed glasses, and a white “Rhymefest for CPS” T-shirt, Smith told the crowd that the school board controls everything from what kids eat for lunch to how officials spend a $10 billion budget.

“Those members would come from special interests, business,” he boomed at the mic, to a rumble of disapproval. “They didn’t really come traditionally, historically, from our communities.”

‘Very low down on the ballot’

A couple of weeks later, on an overcast Sunday afternoon in late September, Norington-Reaves strode down a quiet residential street on the far South Side, glancing at a phone app where orange dots represented the 200 likely voters she hoped to reach that day with a pair of staffers and a small group of volunteers.

She’d done this before in a high-profile race for Congress and was ready with a polished doorstep spiel.

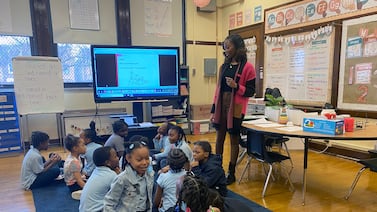

When an 80-something man opened his door, Norington-Reaves started chatting about her experience as a bilingual Teach for America educator in Compton, California, before a career as an attorney and a Chicago workforce development official. She spoke about how she was inspired to run by her experience trying to line up school district services for her daughter, a high-achieving student born without eyes.

“If this was hard for me, what is it like for the average parent who doesn’t have everything I have?” she told the man.

But the man, a retired teacher, was confused. Didn’t the mayor appoint the school board?

“How do you vote for members of the school board?” he asked.

Norington-Reaves had already participated in a dozen community forums about the school board elections and filled out numerous candidate questionnaires. She’d spent eight hours or more knocking on doors every weekend. Chicago’s school board was in the news a lot because of a push by the mayor and teachers union to oust the district CEO. Despite all that, amid the high-pitched noise of a presidential election year, most voters she spoke with still didn’t know about the school board race.

She explained to the man that the mayor would no longer pick all the board members. By 2027, all would be elected.

“It’s very low down on the ballot,” she said. “I’m No. 103.”

“I promise I will vote for you,” the man said.

Campaign cash flowed into the races

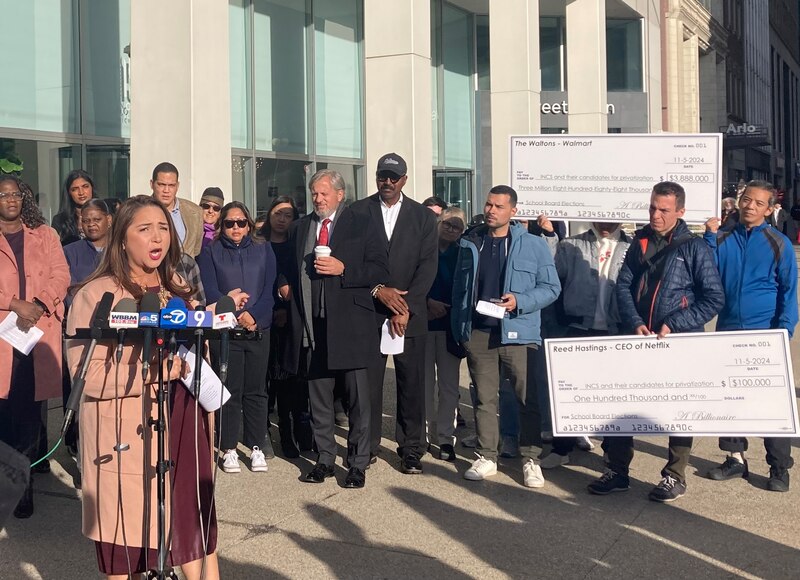

By early October, money was flowing into and out of school board candidate campaign coffers. At that point, the CTU was among the largest spenders, helping their endorsed candidates with field staff and other in-kind support. Then the Illinois Network of Charter Schools unleashed a half a million dollars to support people who favored school choice — doubling all spending to that point. Spending only ramped up from then on.

Jones, the pastor at Bronzeville’s Mt. Carmel Missionary Baptist Church, became one of the candidates citywide with the largest war chest, thanks to the CTU. He had connected with teachers union leaders in 2015, during a 34-day hunger strike he’d joined spur of the moment to keep Dyett High School open. Now on the campaign trail, he often brought up the strike and echoed key union priorities, such as expanding school staffing and a program called Sustainable Community Schools, in which campuses get extra funding to team up with nonprofits and boost after-school programs, family engagement, and more.

On a warm late October morning, he stood on the edge of a semicircle of elected officials, advocates, CTU members, and fellow school board candidates on a busy street in the Loop. The union had organized a press conference in front of the offices of the Illinois Network of Charter Schools to decry school board campaign spending by the group, fueled by large checks from wealthy people in and outside of Illinois. They were calling for new campaign finance limits.

At the event, State Sen. Robert Martwick, an architect of the 2021 law that green-lit an elected board in Chicago, vowed to push for such legislation, perhaps modeled on cities where candidates only receive a limited amount of taxpayer funding to campaign. He acknowledged a strategy of ushering in an elected board — and leaving the details on how it would be elected for later.

The previous week, Jones’ opponent, Norington-Reaves, had found a glossy flier in her mail featuring a faceless marionette in a suit and tie, along with the message, “Donald Trump and out-of-state billionaires are pulling the strings of Karin Norington-Reaves.” She’d laughed. She was a lifelong registered Democrat who ran for Congress as a Democrat with then-outgoing Congressman Bobby Rush’s endorsement. Not to mention she considered Trump “the most vile individual in American political history.”

The misleading mailer was paid for by the CTU, which justified it based on the $250,000 spent by the Illinois Network of Charter Schools and another super PAC to support Norington-Reaves. Those super PACs can pump unlimited dollars in the race as long as they do not coordinate with the candidates.

Meanwhile, Jones also bristled at fliers that took his campaign materials and swapped out his photo for the mayor’s, warning voters he was running to do Johnson’s bidding. The CTU’s backing was crucial to his campaign. The union had brought in his field organizer, Abierre Minor, who pushed out text messages to voters and supporters with sign-ups for phone banking and canvassing. More than 40 volunteers had signed up. But Jones felt he was his own candidate, a longtime supporter of labor that labor was now supporting back.

That October morning, Jones stepped up to the mics. He spoke about his participation in the Dyett hunger strike. Then, glancing at notes, he said, “Our children are not for sale. Our schools are not for sale. Our city is not for sale.”

Focus on students blurred by soundbites

A week later, on a cool, cloudless Sunday morning, Parrott-Sheffer stood by the parking lot of the Southside YMCA in Hyde Park, an early voting site. When potential voters approached, he and several campaign workers for his opponents closed in. He pressed his campaign bookmark into their hands.

“Adam Parrott-Sheffer, Kenwood Academy parent, 20-year educator, hoping to earn your vote,” he rattled off as some strode by briskly.

In March, Parrott-Sheffer became the first candidate across the city to file campaign finance paperwork. Since then, he had tried to be everywhere. He attended school registrations, parades, mornings at the farmers market. He sat on 21 school board candidate panels, filled out 25 questionnaires, and spent time on social media, “an old guy learning a lot about TikTok.” He felt strongly the board needed more parents and seasoned educators like him.

Still, Parrott-Sheffer knew he was a long-shot candidate. He’d never run for office before and was handily outspent. He is also a white guy who was running for office against three Black opponents in a predominantly Black district in a segregated city whose political dynamics have been historically shaped by race and ethnicity.

As Election Day approached, more and more voters had asked where Parrott-Sheffer stood on the mayor. The entire school board had resigned under pressure to fire Martinez, the district CEO. Then, just a week after Johnson hurriedly hand-picked a new board, its new president resigned over antisemitic and misogynistic social media comments.

The drama was not playing well with parents and taxpayers, Parrott-Sheffer thought. It was giving non-CTU endorsed candidates like him a boost — but not that morning outside the YMCA.

A middle-aged woman dressed up in a pink jacket and long white skirt stopped to hear his spiel. Parrott-Sheffer started talking about beefing up services for students with disabilities and English learners, the importance of making sure students can learn by third grade, and the need to fix the district’s aging school buildings.

The woman nodded approvingly and then cut him off: “Are you working with Brandon Johnson?”

“I’m not working with Brandon Johnson,” he told the voter that morning. “I am an independent candidate.”

She pulled back and frowned: “Why are you not working with him?”

Is this what democracy looks like?

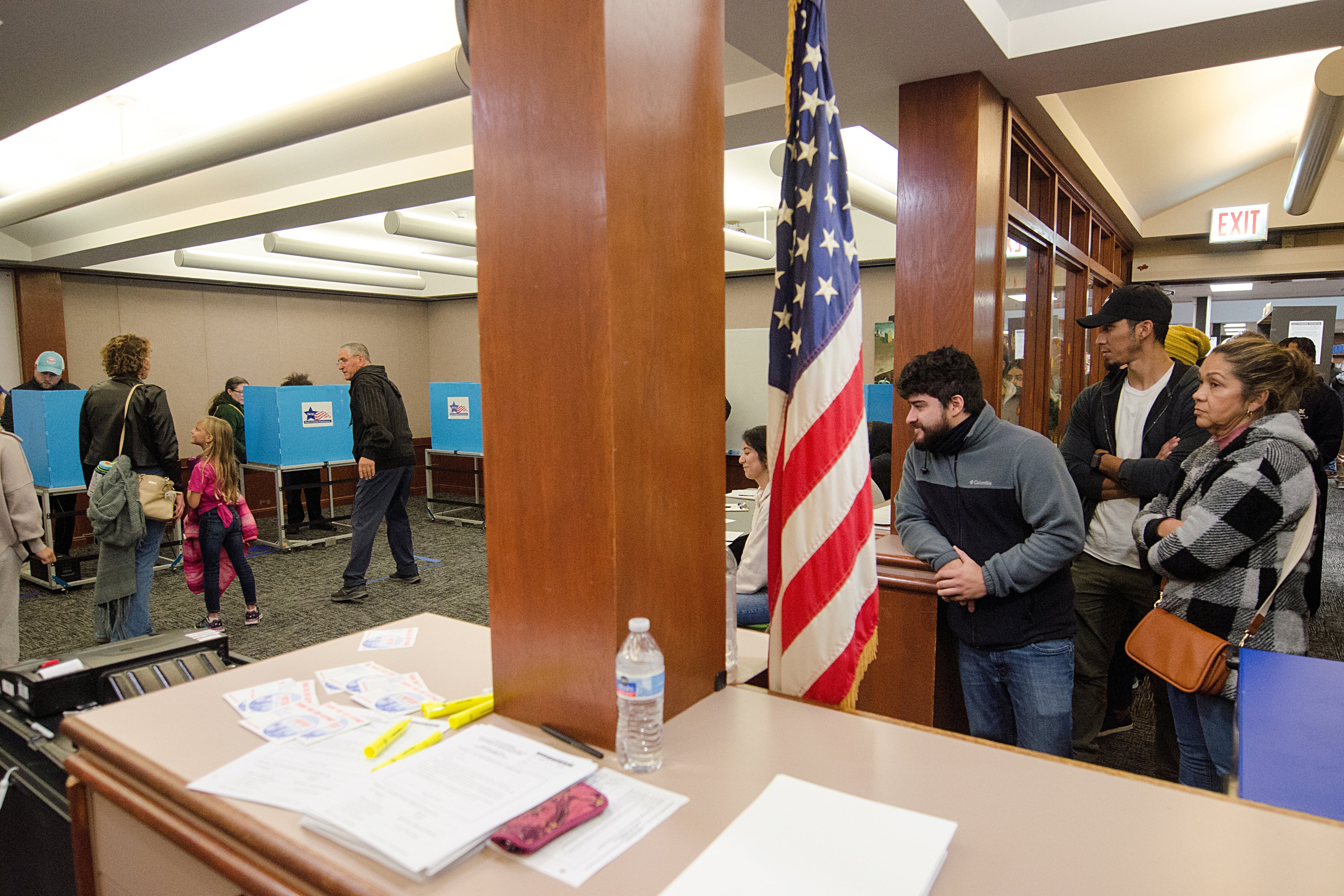

The District 10 candidates greeted Election Day with a mixture of hope, excitement, and unease.

Parrott-Sheffer felt he had given a robust campaign his all. It just saddened him that at a time when the school district faced a leadership and financial crisis, the complex, nuanced education issues of the day were conflated to neat soundbites, a nifty dichotomy: Were you with the mayor and his friends at the CTU? Or were you with the charter people, which made you a Trump puppet, despite the often bipartisan nature of both support and scrutiny of these schools over the years?

Smith felt his bid to cast himself as a changemaker had resonated with voters at a time of flux, even as the media and opponents hadn’t always taken him seriously. Norington-Reaves was worn out from months of juggling campaigning, a demanding job and motherhood, but also energized by honing her voice on the campaign trail. Jones had lost two belt loops door-knocking and talking to voters, leaving him feeling more connected to his South Side neighbors.

It would take until the Friday after the election for the Associated Press to call the District 10 race for Smith, one of the closest in the city. He led with about 32% of the vote, to Norington-Reaves’ 29%. Jones came in third, and Parrott-Sheffer fourth.

As of Thursday, Norington-Reaves had not conceded, noting that thousands of mail-in and provisional ballots are still being counted. She has also threatened to sue the Chicago Board of Elections over issues in District 10 and others where election judges handed some voters ballots for the wrong school board districts.

The Chicago Board of Elections has acknowledged the issue but insisted it was fixed quickly and chalked it up to human error. After all, the school board races were new, and the electoral district boundaries drawn by state lawmakers six months earlier did not align with preexisting precincts and wards. But Norington-Reaves says the problem took hours to address in some precincts. “Potentially thousands of voters were disenfranchised,” she said the Friday after the election.

Across the city, candidates endorsed by the CTU — famed nationally for its ability to put boots on the ground and turn out voters — faced a surprisingly uphill battle. Three out of the nine who had competitive races prevailed, joining one, Jitu Brown, who ran unopposed, on the new board. Three candidates backed by the charter network won their races, and so did three independents — all on the South Side.

Money had mattered across the city — to a point. In District 10, Smith spent about $5 and Parrott-Sheffer spent roughly $6 for each vote they had earned, based on campaign finance records as of Nov. 12 and total votes counted as of Nov. 14. Norington-Reaves and groups spending on her behalf had spent about $20 per vote while Jones spent almost $27 per vote.

According to the Chalkbeat analysis, the CTU and several allied groups largely funded by the union spent about $2.3 million. The charter network and Urban Center super PACs spent roughly $3.5 million.

Longtime elected school board champions say the city must reckon with the ups-and-downs of the races ahead of 2026. Natasha Erskine, who leads the nonprofit Raise Your Hand, which observed ballot petition hearings, believes the signature threshold should be lowered. The hearings were an exercise in “the Chicago way,” with some well-qualified candidates booted and those with more resources enjoying a clear edge.

The nonprofit, which fought for an elected school board for years before the state law was passed, hosted “mini teach-ins” before its candidate forums to educate them about what the school board actually does. It wants to see more parents and seasoned local school council members run. It also supports setting some limits on big campaign spending.

“We were expecting it but, man, we weren’t expecting that,” Erskine said.

State Rep. Ann Williams, a sponsor of the elected school law, said voter awareness and excitement about the election did rise over time, making the school board “the hot race” on the ballot. She felt it featured many candidates eager to have substantive conversations about the issues — but who struggled not to be pigeonholed. Ellen Rosenfeld, a candidate backed by Williams, criticized the mayor and CTU but also put out a release distancing herself from the pro-school choice money spent on her behalf.

Williams feels the ballot threshold is right, noting that it will become 500 signatures in 2026 when the 10 districts become 20. She and other lawmakers are open to proposals to finetune the process.

In the meantime, Johnson is poised to still hold sway over the school system as he must now appoint 11 members to the 21-member board by Dec. 16. But five newly-elected members are asking the mayor and his current board to exercise restraint by not taking any major actions until the new board is seated.

In the days after the vote, Smith made a plan to call the other two independent winners, Therese Boyle and Jessica Biggs. They needed to band together ahead of January, he told them.

Becky Vevea contributed to this report.

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.