Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest news on Chicago Public Schools.

Kimani Vines wanted to carry on her family’s legacy of joining the military. The Englewood STEM High School sophomore is enrolled in her school’s ROTC program and even poses like a cadet for photos – shoulders back, head up, hands clasped.

But after touring colorful booths last month at Chicago Public Schools’ college and career fair for students with disabilities, Kimani grew unsure about her plan. What if, for example, she studied animation before joining the Navy?

“I just wanted to come and see the different job opportunities I could get,” she said. “I was thinking of going to the Navy at first, but now the decision’s kind of changed, and I still don’t know what I want to do.”

Kimani is one of more than 50,000 students in Chicago Public Schools with a documented disability and specialized learning plan to support her academically.

The Student Transition FAIR — Fostering Access, Independence, and Responsibility — held last month at Malcolm X College in partnership with City Colleges of Chicago is one opportunity students with disabilities have to explore their options for life after high school.

Over two days, teachers, counselors, and other school support staff from 46 high schools brought about 700 students, who could check out booths staffed by representatives from colleges and employers, as well as a virtual reality area related to trade jobs and a room for mock interviews.

Just over 16.4% of Chicago Public Schools students have documented disabilities, a percentage that has grown in recent years. The district has historically struggled to provide required services to students with disabilities, who are less likely than their peers to graduate on time. Last school year, just over 75% of students with disabilities graduated on time, compared to about 81% of all students citywide.

Even a smaller share immediately pursue college. Of students with learning disabilities who graduated in 2023, about 30% immediately enrolled in a four-year college, while about 18% went to a two-year college right out of high school, according to a study by the To & Through Project and the University of Chicago’s Consortium on School Research. In comparison, more than half of CPS’s graduates without Individualized Education Programs, or IEPs, which map out services for many disabilities, immediately pursued four-year college, and another 15.5% of such students enrolled in two-year programs.

Fair addresses specific needs of students with disabilities

The fair began about a decade ago, according to CPS. While students with disabilities can attend other college fairs, this one is more tailored to their unique needs. That includes connections to community agencies that can provide housing or training opportunities for students with severe disabilities, or trade or career opportunities, transitional day programs, or college preparation programs that don’t exist elsewhere.

“It’s really our responsibility and our system’s responsibility just to make sure that we’re doing anything and everything we possibly can so that students can be ready for that life in the community beyond public school,” said Joshua Long, who oversees the district’s Office for Students with Disabilities.

Long’s office partnered with the district’s college and career division to help host the fair. Megan Hougard, chief of college and career success for CPS, said it’s incumbent upon the district to ensure that all students with disabilities feel like they can access the same opportunities as their peers.

About 8 years ago, CPS added a new graduation requirement that all students — including those with disabilities — must come up with a post-secondary plan.

“If I’m in a senior seminar class, and I’m hearing about all these opportunities, there shouldn’t be a roadblock that we haven’t addressed when we’re saying, ‘What does this mean, then, for students with disabilities in that same class,’” Hougard said. “That’s where I feel a lot of urgency.”

Students practice interview skills, learn about career options

On the morning of the second day of the fair, hundreds of students and teachers walked around a large conference area with multiple rooms in a section of Malcolm X College.

Some visitors approached the college and career booths, including Kimani, the student from Englewood STEM. Kimani said she liked the idea of going to college but wasn’t sold on it, until she talked to a representative from Columbia College.

“After today, I think it’s changed — except for living with a bunch of people,” she said, referring to dorms. Kimani now wants to take early college classes and is wondering if she should pursue a career, such as in animation or personal training, before joining the military.

Kimani’s chemistry teacher, Lakeisha Gosa, brought Englewood STEM students to the fair both days. It was Gosa’s first year, and she said it seemed like a decent chance to expose younger students like Kimani to life outside of school. In Kimani’s case, she pointed out, it had an immediate impact.

The fair also helped prepare some older students for what’s next, Gosa said. Students with disabilities can remain in school until the age of 22; however, once they leave school, they lose their school-based support services.

“We had students that are 18 and aging out, so helping them understand how to have these conversations on their own, because they wont have a service provider once they leave high school,” she said. “So to help them advocate for themselves was a good start for them.”

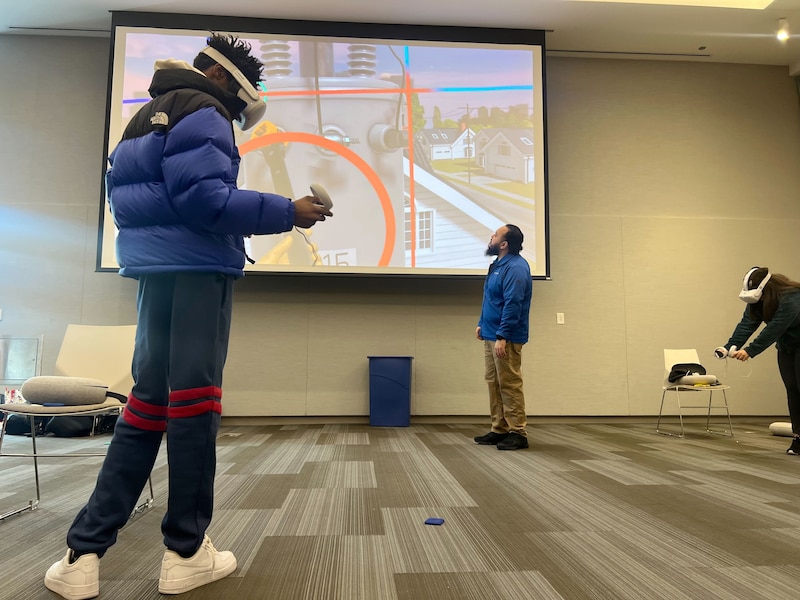

Next to the college and career booths was a virtual reality station. One student wore a large VR headset and waved his arms in the air, practicing what it would be like to fix an electrical pole on the street. His actions were projected on a screen in front of him for the audience to follow along.

In another room, students explored career and trade programs they could participate in while still in high school or how they could find similar programs at City Colleges campuses. In another space, students could watch short films of people with disabilities exploring different college and career options.

Down the hall, several tables were set up in a large open room for mock interviews. At one table, Michelle Burgess, parent support specialist with the Office of Students with Disabilities, posed as the mock interviewer. A student sat down at her table, and Burgess briefly explained the interview process before asking him a handful of basic questions. The mock job was for a certified nursing assistant. The student handed over a resume.

“What would your friends say are your strengths? What would your friends say about you?” Burgess asked.

The student replied: “They would say I’m good at listening. I’m friendly, smart, intelligent, and then of course, of course …” For a few seconds, the student struggled to find the words. Then he said, “Of course, noticing what others do.”

Burgess asked him to say more.

“Essentially like, let’s say I found something people haven’t noticed, or picked up on a cue.”

The interviewer nodded. She told him that was an important skill for the job.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.