Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest news on Chicago Public Schools.

Chicago Public Schools unveiled a five-year plan Thursday to improve the outcomes of the district’s Black students — at a time of unprecedented backlash against efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in education.

The release of the Black Student Success Plan, during Black History Month, is part of CPS’s broader five-year strategic plan and aims to address long-standing disparities in graduation, discipline, and other metrics faced by its Black students, who make up roughly a third of the student body.

The district set out to create the Black Student Success Plan in the fall of 2023, but its quiet posting on Thursday comes as both conservative advocacy groups and the Trump administration are taking aim at race-based initiatives in school districts and on college campuses.

Late last week, the U.S. Department of Education’s top acting civil rights official warned districts and universities that they could lose federal funding if they don’t scrap all diversity initiatives, even those that use criteria other than race to meet their goals. He cited the 2023 Supreme Court Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard decision that banned the use of race as a college admissions factor.

CPS — in a progressive city in a Democratic state — has largely been insulated from standoffs over diversity and inclusion in recent years, when districts in other parts of the country have come under intense scrutiny over how they teach race and how they take it into account in hiring, selective program admissions, and other decisions. Increasingly, though, deep blue cities like Chicago are finding themselves in the crosshairs.

Last year, a Virginia-based advocacy group challenged a Los Angeles Unified School District initiative aimed at boosting outcomes for its Black students, which CPS said inspired its own plan. At the urging of the Biden administration, Los Angeles made changes to downplay the role of race, causing an outcry from some of its initiative’s supporters.

Chicago’s plan vows to increase the number of Black teachers, slash suspensions and other discipline for Black students, and embrace more culturally responsive curriculums and professional development to “combat anti-Blackness” — goals some of which could run afoul of the Department of Education’s interpretation of the Students for Fair Admissions decision.

Still, some district and community leaders in Chicago say CPS’s plan might be better-positioned to withstand challenges than Los Angeles’ initiative — and they said the district must forge ahead with the effort even as it braces for pushback.

“Now is not the time for anticipatory obedience and preemptive acquiescence,” said Elizabeth Todd-Breland, a University of Illinois Chicago professor of African American history and a former Chicago school board member who served on a working group that helped craft the plan. “This is not the time to shrink but to live out our values.”

The new plan says Illinois law mandates this work and cites a state statute that requires the Chicago Board of Education to have a Black Student Achievement Committee. That committee has not yet been formed.

CPS declined Chalkbeat’s interview request and did not answer questions before publication. The district is hosting a celebration at Chicago State University at 3 p.m. Friday to mark the plan’s release.

Chicago set out to create Black Student Success Plan years ago

CPS convened a working group made up of 60 district employees, parents, students, and community members that started meeting in December of 2023 to begin creating its Black Student Success Plan.

The following spring, it hosted nine forums to discuss the plan with residents across the city — what the plan’s supporters describe as one of the district’s most extensive and genuine efforts to get community input.

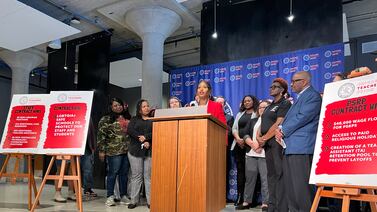

The working group in May released a list of recommendations that included stepping up efforts to recruit and retain Black educators, promote restorative justice practices, ensure culturally responsive curriculums that teach Black history, and offer more mental health and other support for Black students through partnerships with community-based organizations.

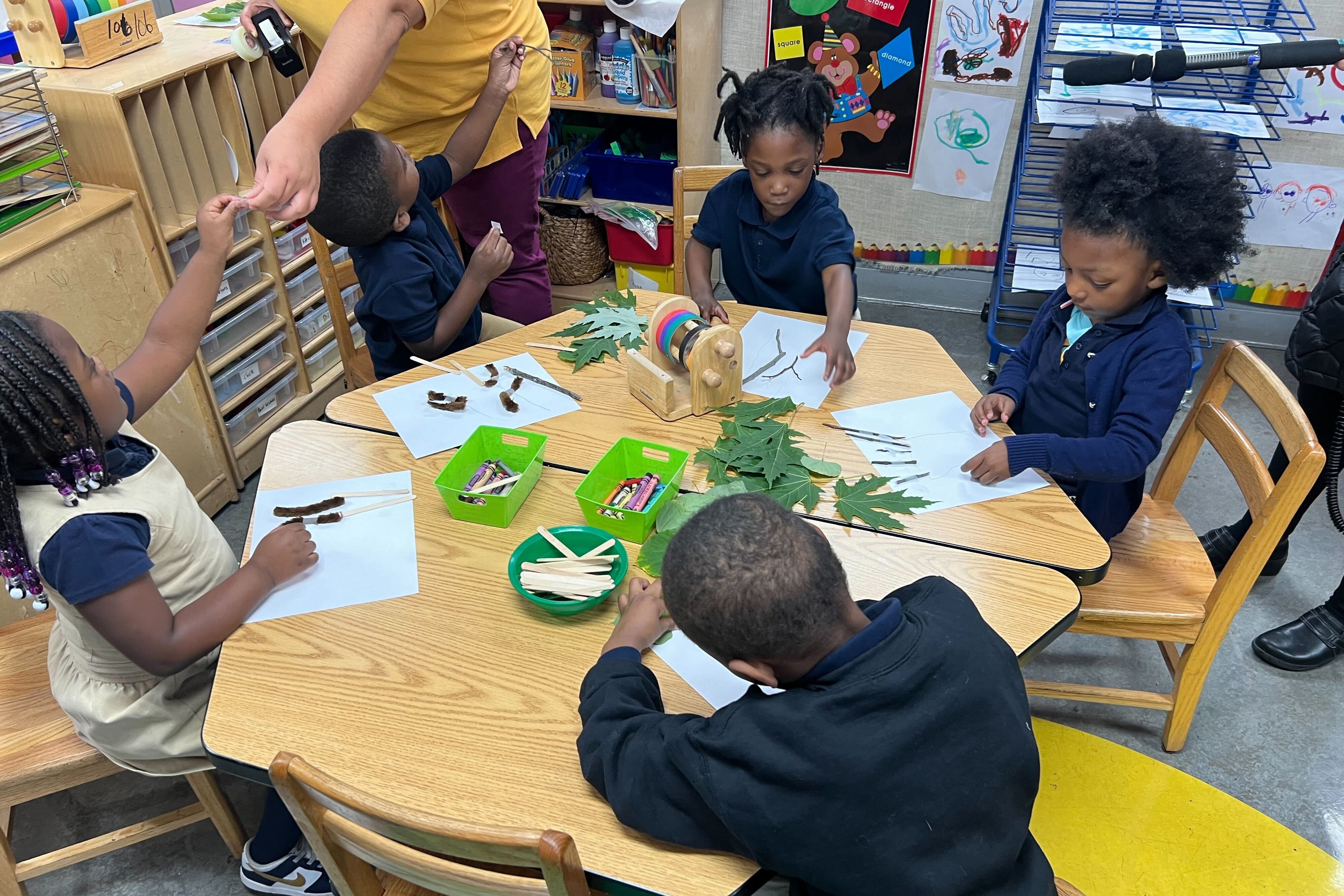

The district adopted many of these recommendations in its plan. It sets some concrete five-year goals, including doubling the number of male Black teachers, increasing the number of classrooms where Black history is taught, and decreasing how many Black students get out-of-school suspensions by 40%.

“The Black Student Success Plan is much more than simply a document,” the plan said. “It represents a firm commitment by the district, a roadmap, and a call to action for Chicago’s educational ecosystem to ensure equitable educational experiences and outcomes for Black students across our district.”

The effort built on equity work to help “students furthest from opportunity” that started five years ago under former CEO Janice Jackson, said Dominique McKoy, the executive director of the University of Chicago’s To & Through Project. In CPS, by a range of metrics, those students have historically been Black children.

McKoy, whose work focuses on college access, points out that the district has made major strides in increasing the number of students who go to college. But more students than ever drop out before earning a college degree — an issue that has disproportionately affected Black CPS graduates.

“There’s evidence and data that we haven’t been meeting the needs of Black students,” he said. “This plan is about responding to the data. Being clear about that is one of the best ways to insulate and defend that process.”

But McKoy acknowledges that now is a challenging time to kick off the district’s plan.

“Undoubtedly there will be critics who will think it’s racial preference to help students who need help and will attack the district for doing so,” said Pedro Noguera, the dean of the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education.

Last year’s challenge against a $120 million Los Angeles program aimed at addressing disparities for Black students offers a case study, Noguera notes. Parents Defending Education, which opposes school district diversity and inclusion programs, filed a complaint with the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. The group has also challenged programs to recruit more Black male teachers and form affinity student groups based on race in other districts.

Ultimately, Los Angeles overhauled the program to steer additional staffing and other resources to entire schools serving high-needs students, rather than more narrowly to Black students. The Los Angeles Times reported that to some critics, those changes watered down the program, which was beginning to show some early results. But Noguera says he feels the program is still helping Black students.

However, it is clear that the Trump administration plans to go much further in interpreting the Students for Fair Admissions decision and seeking to root out DEI initiatives. In a “Dear Colleague” letter to school leaders Friday, Craig Trainor, acting assistant secretary for civil rights in the Education Department, said efforts to diversify the teaching force or the student bodies of selective enrollment programs could trigger investigations and the loss of federal funding. About 20% of CPS’s operating revenue comes from the federal government.

“The Department will no longer tolerate the overt and covert racial discrimination that has become widespread in this Nation’s educational institutions,” Trainor wrote. “The law is clear: treating students differently on the basis of race to achieve nebulous goals such as diversity, racial balancing, social justice, or equity is illegal under controlling Supreme Court precedent.”

‘Get the help to the kids who need it’

Chicago, like Los Angeles, might consider a focus on schools — chosen based on metrics such as graduation rates, test scores and others — where the plan would help Black students and their peers, Noguera said. Maybe it doesn’t even have to refer to Black students in its name, he said.

“The main thing is to get the help to the kids who need it,” he said. But, he added, “In this environment, who knows what’s challenge-proof.”

He said what helped in Los Angeles was deep community engagement that lent that district’s initiative credibility and good will; the changes that the district made in response to the legal challenge did not erode those.

Darlene O’Banner, a CPS great-grandmother who served on the working group, said CPS got the community engagement piece right. She thinks the plan will offer a detailed roadmap for improving Black students’ achievement and experience.

“I am not going to think of the unknowns and what’s going on in the world,” O’Banner said. “We’re just going to hope for the best. We can’t put the plan on hold for four years.”

The working group issued its recommendation in early fall and stopped meeting following the September resignation of all school board members, who stepped down amid pressure from the mayor’s office to fire CPS CEO Pedro Martinez over budget disagreements.

Valerie Leonard, a longtime community advocate who also served on the working group, said during the community meetings for the Black Student Success Plan last year, there was no discussion of possible legal pushback to the plan.

“Illinois is a liberal state,” she said. “It never really occurred to us a year ago that this plan would be in danger.”

But more recently, as she heard Trump assail DEI initiatives, Leonard said she wondered if the plan would survive.

Leonard pushed Illinois lawmakers last year to mandate the Board of Education appoint a Black Student Achievement Committee as part of the state law that cleared the way for an elected school board in Chicago. The district’s plan invokes that committee though it hasn’t been formed yet. The board formed a more generic student success committee earlier this month.

“We believe that the problem with Black children in public schools is so dire that it needs to be elevated to its own committee,” she said. “When our children get lumped into something that’s for all, they inevitably fall between the cracks.”

McKoy at the University of Chicago said he feels “cautious optimism” and hopes the city and state rally around CPS as it pushes to improve outcomes for Black students.

“The plan itself isn’t going to do the work,” he said.

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.