It was late fall. Several mothers gathered in the art room of Tennyson Knolls Elementary School for a parenting class. One of the leaders asked how their week had gone.

Teresa Morton spoke up. She’d recently worked several late shifts as a cashier at Kmart and felt guilty about the time away from her son Sammy. The first-grader was used to her busy work schedule. Maybe too used to it, she thought.

She started to cry.

It was a hard moment for Morton, but the two co-leaders and her classmates soon offered tissues and comforting words.

“I felt like I was talking to my best friend,” she said. “I got emotional.”

The tearful moment during a class called “The Incredible Years” offers a glimpse into an ambitious project that aims to improve the educational outcomes of students at this low-income school northwest of Denver.

Called “Blocks of Hope,” the effort began in the summer of 2014. It’s modeled on the Harlem Children’s Zone in New York City and tackles one of the biggest questions in education: What can be done to mitigate the pernicious effects of poverty on student success?

The project’s leaders from the nonprofit Growing Home believe the answer is a “place-based” approach that provides young children in a tightly defined geographic area with everything they need to succeed.

For kids like Sammy, that means new backpacks and school supplies when school starts, Christmas presents in December and weekly tutoring throughout the year. It also means extra support for his mom, including free classes on parenting and early literacy and one-on-one help from family outreach workers.

There are other offerings too—Thanksgiving meal baskets, thrift store vouchers and home visiting services for parents with babies and toddlers, to name a few.

In short, Blocks of Hope aims to provide a full set of educational and social services to families with children from birth to 9 years old living in Tennyson Knoll’s attendance zone—a 2.25-square-mile rectangle in the suburban cities of Westminster and Arvada and unincorporated Adams County.

Principal Brian Kosena, who started at Tennyson Knolls this year, said his reaction to the project has been “utter disbelief that there’s an organization that’s willing to dedicate so much time and resources … to a single school.”

“This idea of drawing out a grid of blocks on a map and saying, ‘We’re just going to flood this grid with as many resources as we can’ … It’s just been amazing,” he said.

Borrowing from Harlem

While the Harlem Children’s Zone has road-tested its unique brand of place-based cradle-to-career work for years, the movement is in its infancy elsewhere.

Since 2010, about 60 communities nationwide have planned or launched place-based projects focused on birth through college, according to a group called the Promise Neighborhoods Institute, which provides technical assistance for such efforts. Many of these initiatives are clustered on the coasts and in the Midwest, and most are in urban areas.

Until Blocks of Hope, such projects have been largely absent in Colorado.

One similarly-themed initiative, “The Children’s Corridor,” launched in northeast Denver and northwest Aurora five years ago but was phased out within a few years. Part of the problem was the huge 41-square mile target area covering multiple cities, counties and school districts.

With no clear precedent here, Blocks of Hope represents both a promising experiment and an untested investment.

Experts say when such place-based efforts are done right—with a long-range timeline, deep community penetration and a hard-nosed focus on results—they can move the needle on educational outcomes.

“What this focus on a particular school and a particular place brings is a much finer-grained focus on why kids are not making it,” said Frank Farrow, director of the Center for the Study of Social Policy, one of three partners in the Promise Neighborhood Institute.

“We call it place-based,” he said, “but really it’s that intensity of intervention and that accountability for every child.”

“We’re not doing enough”

While Blocks of Hope officially launched last year, the idea crystallized in the mind of Growing Home’s director and CEO Teva Sienicki in 2008.

It was then, as she bustled around the Growing Home office, that she saw two boys gazing intently at something while they waited for their parents to complete a rental assistance interview. When she realized the pair was transfixed by a bowl of fruit in the nonprofit’s day center, she offered them each an apple.

“They ate that thing literally not just to the core, but to the seeds and the stem. I had never seen kids eat an apple like that,” she said. “It shook me up. I said ‘You know, we’re not doing enough.’”

Sienicki began looking at the national landscape to see what kinds of programs were making a difference. That’s when she came across the Harlem Children’s Zone, the brainchild of founder Geoffrey Canada.

But 2008, in the midst of the recession, was a bad time to start new programs.

Still, the Growing Home team agreed to begin bulking up services, laying the groundwork for the launch of Blocks of Hope at one school in the Adams 50 district. The 10,000-student district is one of more than 15 community partners involved in the project.

It would be a scaled-down version of the Harlem model, focusing on children from birth to 9 instead of the full “cradle-to-career” span.

Both Sienicki and the district’s director of early childhood education, Mat Aubuchon, believed the early childhood focus made the most sense.

“We’d love to have something like what Geoffrey Canada did, of course,” said Aubuchon, who’s worked closely with Growing Home on the project. “I think you also have to look at the scale and the size, and say, ‘What can you realistically pull off?’”

Help for a struggling reader

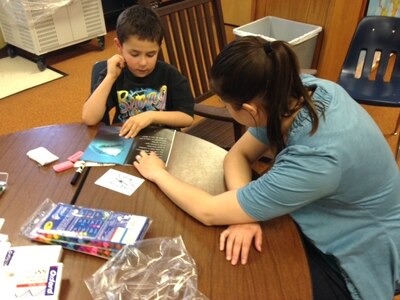

One afternoon last April, Dana Morton—Teresa Morton’s younger sister— brought her first-grader Natasha to a Blocks of Hope tutoring session in the Tennyson Knolls school library. Her nephew Sammy was there, too.

While Natasha worked on a reading activity with a volunteer and Morton’s toddler daughter Katrina played on the carpet, Morton confided in Dolores Ramirez, a bilingual family support specialist from Growing Home.

“I have a feeling that she’s going to fall behind,” said Morton, recalling Natasha’s summer slide the previous year. “She’s having trouble reading.”

Ramirez, who spends several hours a week working with families at the school, gently prodded. She asked if Morton had talked to the teacher about her concerns or could ask the teacher to write a letter advocating that Natasha be enrolled in the district’s extended school year program.

In the end, Natasha didn’t get into the program.

But as Natasha — who has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder — entered second grade still struggling with reading basics, Dana Morton remained concerned.

She circled back to the subject on a September afternoon as she and her sister Teresa chatted in front of Tennyson Knolls as they waited for their kids to be dismissed. Natasha had done poorly on a back-to-school reading assessment. Morton planned to stick with Blocks of Hope tutoring and push for the extended school year program next summer.

The Morton sisters, who attended district schools themselves for several years, live with their parents not far from the school. Dana, a stay-at-home mom, receives Social Security income because of a persistent back problem. Teresa hopes eventually to go to nursing school.

As students poured out of the school’s front entrance just after 3 p.m., Teresa talked about her plans to attend a Blocks of Hope class on early literacy development the following night. Not so much for Sammy, who loves to read, but for her niece Natasha.

“I’m doing it more for her because she’s so far behind,” she said.

Planning for expansion with a gentrification caveat

At the moment, Blocks of Hope is a relatively modest project—with two dedicated employees, several employees with part-time involvement and an annual budget of $250,700. But Growing Home leaders have much bigger plans in store.

First, they envision a 20-year investment in the effort. Over that time, they anticipate a major expansion of the project as it grows to include the attendance areas of two nearby elementary schools: Westminster and Harris Park. They’ve also talked about adding a fourth elementary school—Hodgkins—to the mix.

Snapshot: Demographics of schools envisioned as part of Blocks at Hope

When it’s fully scaled-up, Sienicki projects that Blocks of Hope could have up to 70 dedicated employees and a budget of $3-$3.5 million.

Together, Tennyson Knolls, Westminster and Harris Park educate just over 1,000 students, more than 80 percent from low-income families. Academic achievement is lackluster, with only 43-44 percent of the schools’ third-graders reading proficiently, according to 2014 state test results.

This corner of Adams County presents other challenges too. In a survey conducted in the Tennyson Knolls enrollment zone by Growing Home staff, residents expressed concern about the lack of afterschool and summer programs for kids and the dearth of affordable childcare.

One mother of three confided to Growing Home staff that she’d once had a brick thrown through her front window while her family watched Monday Night Football.

Increasingly, residents are also worrying about the shrinking stock of affordable housing, partly due to construction of two nearby commuter train stations set to open in 2016.

Sienicki said because of alarm about rising rents, Growing Home is in the process of hiring a community organizer to work with Blocks of Hope residents to advocate for affordable housing units in new developments.

While she’s hopeful that families won’t be pushed out of the neighborhood in a tide of gentrification, she acknowledged it’s a possibility—one that could require a shift in the project’s long-term strategy.

Finding a way to pay for it

Outside experts laud Growing Home’s start-small approach and long-term commitment, but there are still plenty of unknowns. Not least among them is where the money will come from, especially as the project grows.

“Realistically speaking, this isn’t free,” said Kosena, the Tennyson Knolls principal. “And it’s not like they’re charging families and they don’t charge my school budget.”

Currently, Blocks of Hope receives funding from around a half-dozen sources, including foundations, private donors and local government.

In 2009, Growing Home applied for a federal Promise Neighborhood grant for the project, and a few years later pursued a funding mechanism called “social impact bonds,” in which private investors pay for interventions up front and get their money back if the programs produce results. Neither option panned out.

While the nonprofit has received some key grants for Blocks of Hope and hopes a new District 50 effort to explore social impact bonds could eventually support the project, Sienicki is candid about the financial challenges.

“Money is a constraint,” she said. “That’s the story of this work. If we were able to have the resources that we needed, we would have scaled up already.”

Such difficulties are typical, said Farrow, of the Center for the Study of Social Policy.

“On the one hand, I think private funders find it compelling because it’s an overall vision, it’s not just an isolated program…but I think for some local funders, if they’re not geared to or don’t have enough resources to think long term, it can be intimidating as well.”

Changing neighborhood norms

While Blocks of Hope is hardly an exact replica of the Harlem Children’s Zone, it’s similar in its aim to provide services to a critical mass of neighborhood families. The hope is that eventually the project will touch at least 60 percent of families with children — a tipping point, so to speak, that will benefit the whole service area.

The tipping point concept is based on a simple premise, said Kwame Owusu-Kesse, the Harlem Children’s Zone’s chief operating officer.

“Kids are doing what their friends are doing,” whether that’s studying hard or smoking weed, he said. “So how do we shift the norms of the community?”

In year one, Blocks of Hope reached about 10 percent of families with children in its target area. The goal for this year is 20 percent.

Farrow said it often takes a decade of concerted place-based work to see a big impact.

“I think you definitely see small-scale results in two to three years,” he said. “In five years, you could see really significant results, but not what people are calling population-level change.”

No instant outcomes, but data will drive decisions

Besides a long-term commitment and community buy-in, outside observers say successful place-based work requires data-driven decision-making and a willingness to make changes when things aren’t working.

Sienicki, who’s been at the helm of Growing Home since 2002, agrees.

“One of our core values is effectiveness…We want to do what works,” she said. “We want to look at the data. We want to look at the research. We want to look for the results.”

Among the performance metrics that will be tracked as part of Blocks of Hope are school attendance rates, kindergarten readiness assessments, third-grade reading scores and rates of referral to special education. There are also plans to assess family functioning before and after services and examine changes in the school’s mobility rate, which measures the percentage of students who move into or out of a school in a given year. Tennyson Knoll’s mobility rate was nearly 14 percent in 2014.

Sienicki said it’s too early to see any major changes in student outcomes. Still, she said there have already been shifts in awareness, attitudes and behaviors among parents who’ve taken Blocks of Hope classes, which are offered in both English and Spanish.

One such parent is Brittany Hanes, a single mom who works full-time taking reservations for a video conferencing company. She and her son Jayden, a second-grader at Tennyson Knolls, live with her parents.

Hanes said The Incredible Years class she took last year through Blocks of Hope helped her adopt better habits as a parent: Things like establishing a nightly homework routine for Jayden, learning the names of his friends and attending as many school events as she can.

Her childhood in the Adams 50 district was different. It was chaotic and unstructured. She struggled with reading and dallied on homework. Her parents rarely attended school events.

“I don’t feel like I was pushed,” she said.

She hopes to change that trajectory for Jayden and she believes Blocks of Hope will give her the tools.

“I know now if they’re offering something, really and truly we need to take it,” she said.

“When the help comes to you and you don’t have to go out reaching for it, that changes things,” she said.

Looking toward the future

As year two of the project unfolds, leaders at Growing Home are optimistic. School and district staff are supportive and participation among Tennyson Knolls families is growing.

There are also new offerings coming online. Later this year, Blocks of Hope will launch a program for prospective and new parents called “Seedlings,” modeled after the Harlem Children’s Zone’s well-known “Baby College.”

That doesn’t mean there haven’t been growing pains. Aside from big-picture issues like funding challenges and shifting housing trends, there are plenty of day-to-day logistics to navigate.

For example, space constraints have stymied plans to open up a used clothing boutique in the school where parents could use vouchers to shop for their children.

Other challenges include a couple of community partnerships that haven’t panned out as Sienicki hoped and the tricky job of channeling services to the Tennyson Knolls community while still providing certain Growing Home services to other Adams County residents.

Overall, though, she said, “On the ground, it’s actually in many ways come out just as well or better than we could have hoped.”

One of the newest Blocks of Hope programs, “Reading Explorers,” was unveiled in mid-September during an all-school assembly in the gym.

Rebecca Zamora, manager of early childhood initiatives at Growing Home, told the 375 students sitting cross-legged before her that they would get stamps in their new literacy passports by attending “story walks” at different community locations. Prizes would follow at the end of the year.

“Sound good?” she said. “Who’s ready to read?”

The students raised their hands and applauded.