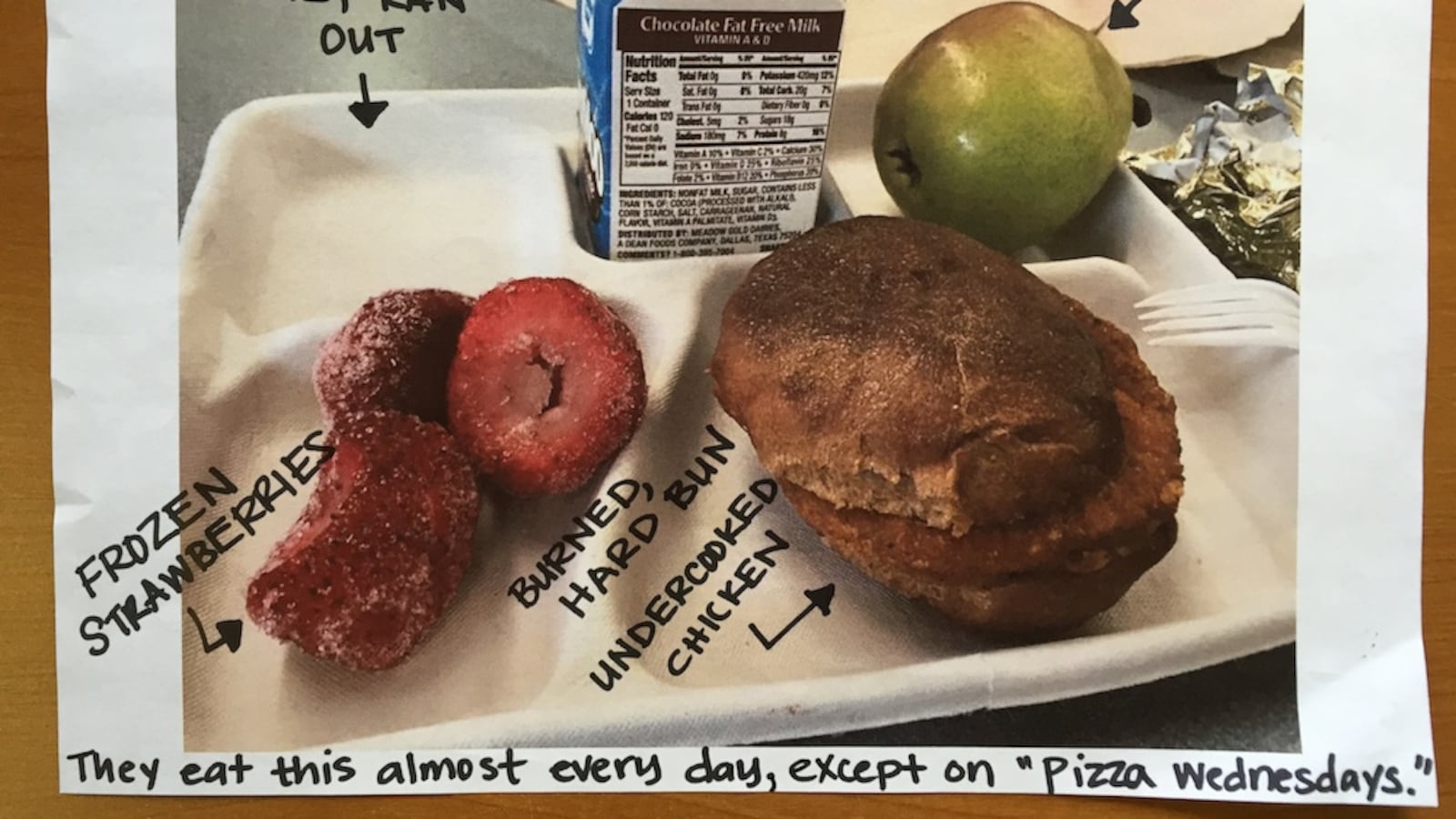

The story didn’t start with the burned sandwich bun or the still-frozen strawberries on the lunch tray at Kepner Middle School in Southwest Denver. It started months earlier with a slow simmer of dissatisfaction over the quality of the school’s food.

But when that meal was served on May 12 during a lunch visit by school board member Rosemary Rodriguez, a district administrator, and representatives from Padres y Jóvenes Unidos, it perfectly captured the ongoing complaints: Food wasn’t prepared properly, some items ran out before the end of lunch, and there weren’t enough choices.

It was a Kepner student named Stephanie Torres, speaking about Padres’ health justice platform, who helped sound the alarm about such problems at a school board meeting in April. Her remarks spurred plans for the lunchtime visit by district officials. The visit, while coordinated in advance by central administrators, was not announced to Kepner’s kitchen manager or principal.

Monica Acosta, lead health justice organizer at Padres, went along on the visit and snapped a photo of her lunch tray.

“It was heartbreaking. That’s the type of food Kepner students have been having all year long,” she said.

In the last three weeks, Torres, Acosta, and others who participated in the lunch visit have reported positive changes in Kepner’s cafeteria.

There’s no more frozen fruit or expired milk, and there are more hot entrée choices. Next year, there are plans to put Kepner on a different meal model that will increase daily hot entrée offerings from four to six, in line with most other middle schools.

“We’re very thankful those changes were implemented immediately,” said Acosta.

She said officials from the DPS nutrition services department have twice met with Padres representatives, including parents from Kepner and other district schools where complaints have surfaced.

“It’s definitely on the right track,” she said.

Navigating a bureaucracy

By most accounts, the changes at Kepner represent a win, but they also raise questions about what caused the problems in the first place, how pervasive meal complaints are in the district, and what mechanisms exist for students and parents to air their concerns about school food.

Theresa Peña, a former Denver school board member and now a district employee, said the nutrition services department is willing to have conversations with students, parents and school personnel about food. In fact, that’s a large part of her new job as the department’s regional coordinator for outreach and engagement.

If there are concerns, she said, “we are absolutely willing to do something different.”

"The biggest complaint I hear from students is the lack of variety."

Still, she agreed that in a bureaucracy like DPS, which serves nearly 80,000 meals at 185 schools a day, it’s not always clear to students or parents whom to approach when there’s a problem. Closing that “communication gap” represents a big opportunity for the department, she said.

There’s been talk about putting kitchen manager’s photos and contact information up in school cafeterias and bringing parents on behind-the-scenes kitchen tours. Currently, the district seeks feedback about school food through student surveys conducted at three mobile food service kiosks. Peña also plans to work with the district’s student board of education to solicit feedback.

“The biggest complaint I hear from students is the lack of variety,” said Peña.

A varied landscape

The problems at Kepner represent a distinct contrast with what multiple observers say is an upward trajectory for meal program quality districtwide.

About five years ago, DPS began moving away from a menu of processed foods to majority scratch cooking. (Both Kepner’s kitchen manager and another employee there have participated in scratch cooking training.)

The district is also well-known for its robust school farm program, which provides thousands of pounds of fresh produce to school kitchens every year. In addition, all district schools have salad bars.

“DPS is really doing some great things,” said Rainey Wikstrom, a healthy school consultant and DPS parent. “I would say one bad apple doesn’t ruin the whole barrel.”

Still, it’s not clear why the burned bun–ironically one of the district’s scratch-made baked goods—or the frosty strawberries were served on May 12.

“In any large district there’s always going to be a difference between the best intentions of the central office and what actually happens in schools,” said Sarah Kurz, vice president of policy and communications for LiveWell Colorado.

While Peña agreed the bun should have been thrown out, she said the Kepner kitchen, like others across the district, has struggled with short staffing throughout the year. She recalled that the workers were barely keeping up when she went through the lunch line herself that day.

Wikstrom said when she recently read a job posting for a school kitchen manager, it hit her hard how much is expected for a relatively low wage.

“We don’t pay our food service staff well…We need to offer them more support and more financial support,” she said.

As for the reason that Kepner students had few entree choices for most of this year, that’s because the school’s kitchen provides meals to a nearby district preschool as well and therefore followed a K-8 menu model. That model includes fewer daily choices than a middle or high school model.

A broader problem?

Kepner is not the only DPS school where complaints have surfaced about school food.

In fact, while lunch was the culprit this time around, breakfast has been a target of complaints in Denver and elsewhere over the last couple of years. That’s because more schools have added breakfast in the classroom since the passage of the “Breakfast After the Bell” law in 2013.

That trend, which often means delivering coolers of food to individual classrooms, has contributed to the use of easy-to-distribute, prepackaged items. Thus, there can be a big disconnect between what is served at breakfast and what is served at lunch.

“Breakfast items are not up to par…with where the lunch programs are” said Wikstrom. “[They] meet the requirements but don’t match the message or the philosophy.”

Padres parent Leticia Zuniga, who has a preschool daughter and first grade son, said through a translator that she is unhappy with how many menu items are flour-based.

Her daughter is clinically overweight and Zuniga worries that school food is not teaching her healthy habits. Her son, meanwhile, is not overweight, but comes home from STRIVE Prep-Ruby Hill two or three times a week saying he didn’t eat lunch.

“He doesn’t like the food,” she said.

In February, two students at McAuliffe International Academy wrote an article for their student newspaper in which they skewered certain hot breakfast items.

The girls wrote: “…it is a disappointment when your teacher opens the hot food container and all you see is half burnt pizza in a bag or half melted omelet in a bag. Even teachers think it’s gross.”

Peña acknowledged such complaints and said the district’s breakfast pizza has drawn particular ire.

She’s heard from multiple parents: “We think the idea of breakfast pizza is just wrong.”