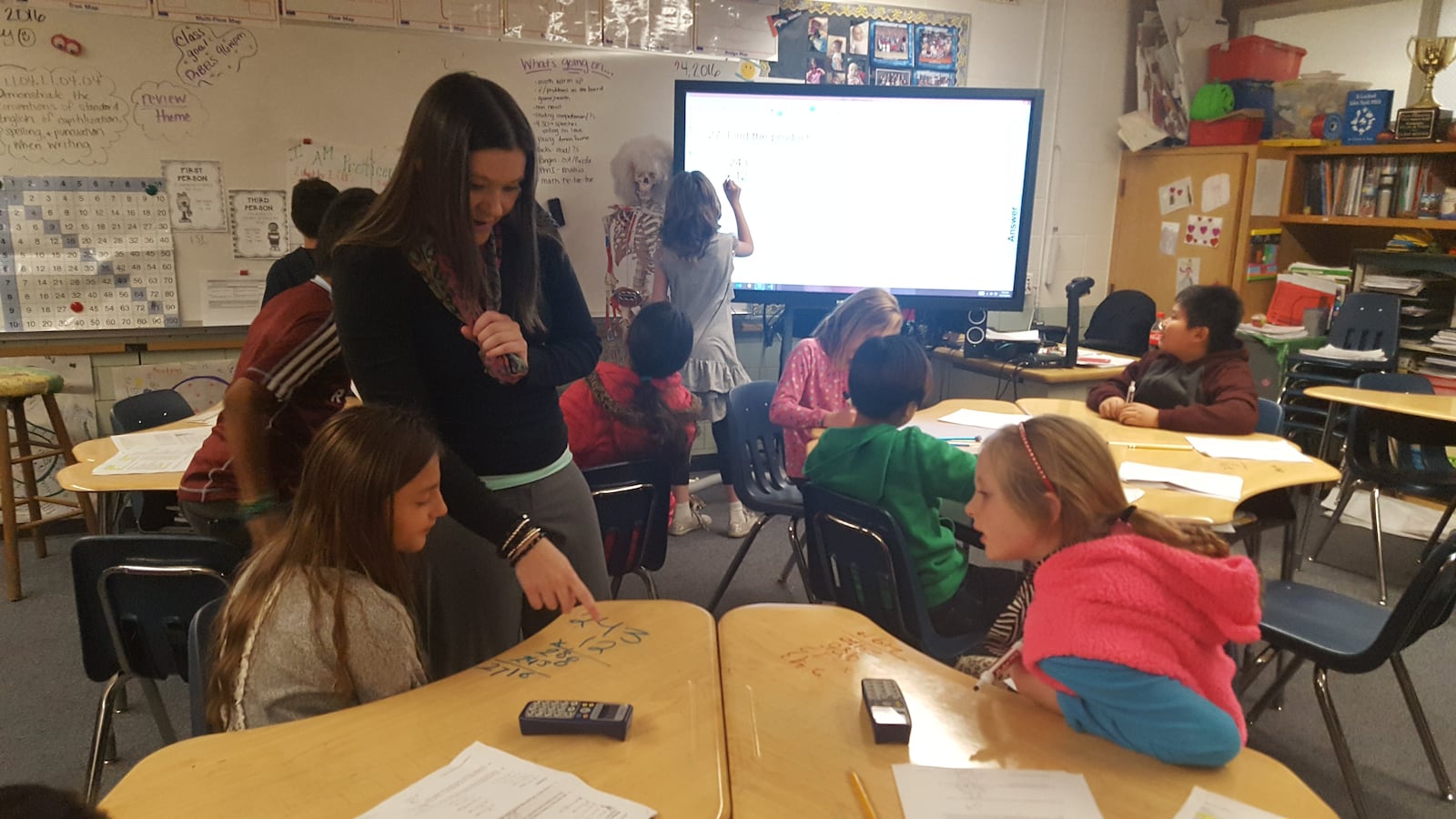

Teacher Amy Adams will tell you that her class at Flynn Elementary School is loud and chaotic.

Her class of almost 30 students is used to doing a lot of independent or small group work. In Westminster Public Schools — the only Colorado district to use what is known as competency-based learning in all its schools — it’s common.

The model does away with traditional grade levels — meaning there is no such thing as third grade, sixth grade and so on. Students are grouped together based on proficiency in each subject, and they are expected to know what they need to master to move up a level. That means during the day, students are moving around, talking to each other and sometimes working on different assignments — raising the volume in the process.

“We don’t like quiet classrooms,” said Justin Davis, principal of Flynn Elementary. “These teachers know what they’re doing. But most importantly, the kids know what they’re working on.”

Seven years since beginning to adopt the competency-based model, Westminster Public Schools is still working out problems and testing changes to try to make the system work, all while the district remains on the state’s watchlist for poor academic performance.

Among the lingering problems: Teachers have been inconsistent in tracking data, the district hasn’t pinned down just how long is too long for a student to linger on a single level, and many students and parents remain confused about how the model works.

Still, the district credits the competency-based model with improving district schools on the state’s performance ratings between 2010 and 2014 so that no district schools are on the state watchlist for a fifth year in a row. That distinction would trigger state sanctions.

But those improvements have not been enough to move the district itself off the watchlist for low performance, according to preliminary ratings. Westminster district officials are contesting this year’s rating, in part insisting the state’s evaluation is not adequately considering their model.

The idea for the new model was simple: Kids should move grade levels when they prove they’ve mastered a learning goal, not based on how long they’ve spent in a class. Students would be grouped in classrooms based on their performance levels and would be able to move levels — or sometimes physical classrooms — in the middle of the year. For state tests, students still must be tested based on their age, not considering what material they’ve been taught based on their proficiency levels.

If the latest rating doesn’t change, the state will decide in the next several months what action to take against districts such as Westminster that have failed to move out of the bottom two performance ratings for five years.

Nationwide, the popularity of competency-based education models is growing. In Colorado, Westminster is the only district using it in all schools and across all grade levels.

Aurora Public Schools included competency-based learning in its innovation plan for Aurora Central High School earlier this year. But officials there said they are still reviewing how it would work and have yet to put a system in place.

As more schools try the model, the research around it is trying to catch up. In a report published last year by CompetencyWorks, an initiative of the advocacy group International Association for K-12 Online Learning, researchers found that school districts switching to competency-based models varied in their time to make the switch. Leaders suggested the first phases took at least five years.

“All the districts highlighted here emphasize they are still involved in continually improving the design and implementation of the system,” the report stated.

In October, Westminster officials presented at a conference in Texas about challenges in tracking how students progress through the levels. This week, district officials will also be in Washington D.C. after they were invited to participate in a White House discussion about improving testing.

Superintendent Pam Swanson has said that it would make sense to test kids “in real time” when they move levels instead of once a year. The tests also need to stay consistent so data can start to be compared and used for more analysis, officials say.

“This progression data doesn’t exist anywhere,” said Jeni Gotto, Westminster’s executive director of teaching and learning. Gotto said having progression data would help teachers plan for students to get on track, and would help the district aggregate data to identify students who are struggling.

Every month, teachers meet with their principal to pore over data about individual students to determine if they’re making progress toward moving levels. Interventionists and psychologists recently began joining those meetings to discuss each student’s needs.

But at a district level, officials couldn’t provide data showing how long students take to move each level compared to how much they should take. Without that, it’s hard to track district-wide trends, including whether any one segment of students is more or less likely to struggle with the model.

Data that is available, such as graduation rates, shows drops. In 2015, 59.4 percent of Westminster students graduated on time, down from 62.3 percent for the class of 2010.

The last two years of PARCC state test scores didn’t show students in Westminster growing much, either. Westminster’s growth scores this year showed students were growing at a slower rate than more than half of the state, and achievement scores also showed several groups performing worse than last year’s classes. For example, among third graders, 15.8 percent of students met or exceeded expectations on English language arts tests in 2016, down from 16.8 percent of last year’s class.

To get more information on progress, Westminster officials last year hired AdvancEd, a national nonprofit, to audit the program.

The group gave the district an accreditation — and a mostly favorable review — but still found many problems and suggested several changes that the district is working on now.

“Many students could describe in varying degrees the concepts of grading and reporting, but often even they could not articulate a simple, clear explanation of the process,” the report stated. “When parents and students do not understand how learning progress is reported, engaging them in meaningful ways becomes much more difficult.”

Teachers say that getting students to take responsibility for their pace of learning is a challenge.

“That’s been perhaps the most difficult — to get the kids to buy into that,” said Westminster teacher Seth Abbott.

Abbott said students in his class have remained engaged by showing their creativity in proving they understand a concept. When he gives them suggestions, they have come up with other ideas including designing a test, he said.

“Everyone learns differently and everyone can show evidence in different ways,” Abbott said. “It’s neat to think of the ways someone can show what they’ve learned in ways I maybe hadn’t even thought about.”

District officials say that’s evidence of positive change that needs time and flexibility to expand.

“Not only have we seen progress,” said Swanson, the superintendent. “We’re still very humble and learn every day.”