The four schools appear to have little in common. One, housed in a building topped with solar panels, is all about sustainability. Another partners with art museums to nurture kids’ creativity. Still another is in the midst of a reinvention to increase test scores while keeping school fun.

All these Denver schools share one important trait. As “innovation schools,” a designation made possible by a 2008 Colorado law, they’re free from certain state and district rules.

They can set their own school hours, choose their own textbooks and hire and fire their own teachers. In terms of sovereignty, innovation schools fall between charter schools, which are publicly funded but operate independently, and traditional district-run schools.

Now, Ashley Elementary School, Cole Arts & Science Academy, Denver Green School and Creativity Challenge Community want even more autonomy, banding together to propose a radical new way to oversee and fund their schools in a district known as a hotbed of reform.

The schools want to form an “innovation zone” that would be overseen not by Denver Public Schools administrators but by a new nonprofit organization that would give the school principals more say in how they spend the state funding attached to their students.

Unlike other innovation zones throughout the country, the Denver zone wasn’t dreamt up by the district as a way to improve low-performing schools and stave off state intervention.

Instead, the idea came from the leaders of the four schools. They claim they’ve pushed their autonomy as far as it can go under the current structure. While they say students have benefitted from the freedoms the schools have exercised thus far, the leaders aspire to do even more.

“It’s all about going from good to great,” said Zachary Rahn, the principal at Ashley.

District officials seem excited about the idea, but it’s not a done deal yet. The players are still negotiating exactly how the zone would work if it were to be approved to operate next year.

Pushing further

There are currently 62 innovation schools statewide. Forty of them are in DPS, a district that prizes entrepreneurship and has embraced alternative school models to what critics say is the detriment of traditional district-run schools.

Each innovation school writes an “innovation plan” requesting waivers from certain state education laws and district policies. Some of the most common — and controversial — waivers deal with teacher employment, salaries and evaluation systems.

Results have been mixed. A 2013 study of several DPS innovation schools found that while teachers reported feeling more empowered, they were also more likely to have less experience and education. Teacher turnover was high, and student academic growth varied widely from school to school.

The 2008 innovation law also allows for the creation of innovation zones by groups of schools with “common interests.” The law requires a group to submit a plan to the local school board and to the State Board of Education describing how a zone would allow the schools “to achieve results that would be less likely to be accomplished by each public school working alone.”

That’s the motivation behind the proposed Denver zone, the school leaders said.

“There’s an incredible value for schools to go through the innovation process,” said Rahn, of Ashley Elementary. But, he added, “there also comes a point where you almost hit a ceiling, where the constraints of the public education system don’t allow you to actualize your plan.”

For example, the leaders said, the district mandates innovation school teachers attend some training that isn’t as relevant to their school’s unique program. DPS also requires innovation schools pay to support certain central-office departments whose services the leaders said they don’t use. And on occasion, the leaders said, they’ve gotten pushback when they’ve tried to carry out initiatives included in their approved innovation plans.

Frank Coyne, who helps lead the Denver Green School, remembers that when his school was opening its garden — a key component of its curriculum — seven DPS department heads showed up with questions. One asked what would happen if a preschooler escaped the fence surrounding the playground, got into the garden, picked a piece of fruit and choked on it.

“They said, ‘You can’t do this,’” Coyne said. “We were like, ‘We’re the Green School!’”

DPS eventually came around, he said. And today, gardens on school grounds are not uncommon. Part of the impetus for the zone, Coyne said, is that “what was innovative five years ago is no longer innovative — and how do we push the envelope?”

The leaders believe that more separation from DPS is key. They want to create an innovation zone that would operate under a nonprofit they’ve named the Luminary Learning Network.

The four schools would remain DPS schools and their teachers would remain DPS employees. But the nonprofit’s board of directors would hire the school leaders. A memorandum between the network and the district would list the schools’ responsibilities and flexibilities.

One of the leaders’ most revolutionary ideas has to do with money. Currently, the state pays school districts about $7,600 per student. But the four schools only get about $5,600, according to Mark Ferrandino, chief financial officer for DPS. The district keeps the other $2,000 to pay for things like transportation, building needs, curriculum, teacher training and administrator salaries.

Originally, the schools floated a proposal to receive the entire $7,600 and then buy back certain services from the district, much like charter schools do. But they’re currently working on a compromise that would give them more than $5,600 per student but less than $7,600.

Mary Seawell, senior vice president for education with the Denver-based Gates Family Foundation (which also provides funding to Chalkbeat) and the former chairwoman of the DPS school board, is working with the schools to develop their plan and negotiate with the district. Former speaker of the Colorado House of Representatives Terrance Carroll, a prime sponsor of the 2008 innovation law, is a founding member of the Luminary Learning Network board.

The school leaders envision that other innovation schools would eventually be able to join the zone. One or two staff members would be responsible for advocating and fundraising for the zone, as well as helping the schools share innovative practices and grow their programs.

If the schools aren’t measuring up, the district would retain the right to intervene. In fact, the leaders are discussing adding even more accountability measures for zone schools.

“We want to serve as a model for what highly autonomous schools and organizations can look like,” Rahn said. “It’s super hard to create systematic change that happens rapidly when you’re talking about hundreds of schools.” But with just four schools, “you can incubate ideas.”

Different schools, same goal

“Innovation” in schools means different things across the country, said Robin Lake, director of the Seattle-based Center on Reinventing Public Education. But for the most part, she said, grouping together schools with more autonomy has been a strategy to improve a district’s worst performers, which she noted hasn’t always been successful. Innovation stands a better chance when it’s not forced, she said.

Two Colorado districts — in Aurora and Pueblo — are currently crafting plans for innovation zones to reverse the course of some of their most chronically low-scoring schools.

Colorado already has three official zones in Kit Carson, Holyoke and the Colorado Springs area. The zone in El Paso County’s Falcon School District 49 is comprised of three elementary schools, a middle school and a high school that work together to create a cohesive experience for students from kindergarten through graduation.

But cohesion isn’t the goal in Denver.

“Each school needs really different things,” said Jennifer Jackson, the principal at Cole.

While the four schools score similarly on the district’s performance scale and have many of the same budget, calendar and employment waivers, the similarities mostly end there.

Cole serves more than 530 kids in preschool through fifth grade in northeast Denver in part of a cavernous middle school building whose hallways are lined with hissing radiators and metal lockers. Ninety-five percent of students are minorities and 93 percent receive free- and reduced-price lunches, a proxy for poverty. More than a third are English-language learners.

For Cole, the journey to innovation was tumultuous. After several attempts to improve the perpetually struggling school, including an ill-fated state takeover, the staff voted in 2009 to become the third-ever innovation school in Colorado. (The first two are also DPS schools.)

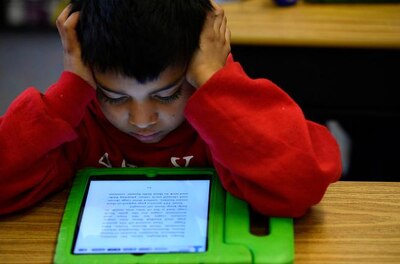

Today, Cole kids wear uniforms: forest green polo shirts tucked in to belted khakis. In one quiet and orderly second-grade classroom earlier this month, students were split into three groups. One watched individualized math lessons on their own computers. Another group solved a word problem involving hamburgers and fractions, while a pair of students worked with the teacher.

When a boy stumbled over the word “grill,” he asked for help. In Spanish, the teacher explained that a grill is like an outdoor stove that might be used to cook carne asada.

Cole’s scores on state tests measuring the proficiency of its third-, fourth- and fifth-graders last year were lower than district averages. But Jackson said the school’s kindergarten through third-graders rank among the top in Colorado for reading growth due to an intense focus on early literacy — promising progress she hopes will show up on future state tests.

Ashley Elementary in east Denver also became an innovation school out of a demand to boost achievement. In 2012, after years of low test scores, DPS got rid of the principal as part of a turnaround effort. Rahn was hired to reinvent the school, which won innovation status the following year. In addition to focusing on academics, he’s worked to inject joy into each day.

The kids started a recent Monday by gathering in the gymnasium of the squat, blond brick elementary school building. Dressed in bright red, blue, green, yellow and orange shirts stamped with the school name, they cheered the Denver Broncos’ Super Bowl win and gave each other shout-outs and awards before heading to class in neat lines.

Ninety-one percent of Ashley’s 400 students are minorities and 88 percent are living in poverty. On state tests last year, they scored below DPS averages but showed high growth in literacy.

One first-grade class spent part of the morning singing words tacked to a “word wall” to the tune of “Frere Jacques.” “Is, in, IIIIIII,” they sang, reading in unison. “It, into, its. If, I’ll, juuust.” When they got to the word “very,” the chorus of six-year-old voices pronounced it “vewwwwy.”

“Way to go me! Way to go you! Way to go us!” they shouted when they finished.

Working within the system

The Denver Green School and Creativity Challenge Community are newer than Ashley and Cole. Both schools had innovation status from the start.

The Denver Green School opened in 2010 with a focus on integrating sustainability into its curriculum. The school serves 535 students in kindergarten through eighth grade, 61 percent of whom are minorities and 60 percent of whom qualify for free- or reduced-price lunches. On state tests last year, their scores were about equal to district averages.

The younger kids attend classes in a decades-old DPS elementary school building, while the middle schoolers occupy a funky “cottage” built behind the playground. Each class has its own plot in the school’s one-acre garden.

On a recent afternoon, fourth graders worked to write newspaper articles about their field trip to the roof, where they learned about the school’s solar panels.

“It’s kind of a good thing,” said one boy dressed in an orange Denver Broncos jersey and blue jeans. “It’s good because it’s clean. It doesn’t pollute the air.”

C3, as it’s known, is the newest of the four schools. It opened in 2012 in a wing of the Merrill Middle School building, in a southeast neighborhood Denver where many parents historically eschewed the local schools because they perceived them to be subpar.

The goal of founding principal Julia Shepherd was to lure some of those families back with an arts-based school that offers hands-on learning opportunities at local institutions like the Denver Art Museum, the Denver Botanic Gardens and the Colorado Ballet.

With just 280 students, C3 is the smallest of the four schools. It has the lowest percentage of minority and low-income students and the highest test scores, far exceeding district averages.

One class of second-graders spent the last part of a recent afternoon engaged in what the school calls “creativity choice.” Some drew with markers, while others built a castle out of wooden blocks. One girl curled up with a book and a group played Apples to Apples with their teacher. When the bell rang, rambunctious kids dressed in sparkly gold leggings and fluffy blue tutus spilled into a messy hallway decorated with quotes from Henri Matisse and Lewis Carroll.

The four leaders recognize the differences between their schools.

“There is no way Cole and C3 have the same needs,” said Jackson, the principal at Cole, where quotes from Maya Angelou and Tupac Shakur hang in the hallways.

And they don’t have to. While the leaders plan to share strategies and resources, their aim is to band together to create a system that allows them to be even more individualized, all the while remaining part of DPS rather than striking out on their own as charter schools.

The leaders hope to present their proposal to the DPS school board for a vote this spring. At a meeting in December, the board unanimously passed a resolution supporting the “promising new innovation” — a move that bodes well for its future approval.

“We’re deeply committed to the district,” Jackson adds. “This is in response to the direction we see them going and the innovation we’re already experiencing. We don’t want to leave the district in order to find a better way to serve kids. We believe we can do that within the system.”