The outcome of a high-stakes legislative fight over health care spending could increase education funding by $90 million next year, but the plan to do that faces big obstacles and questions.

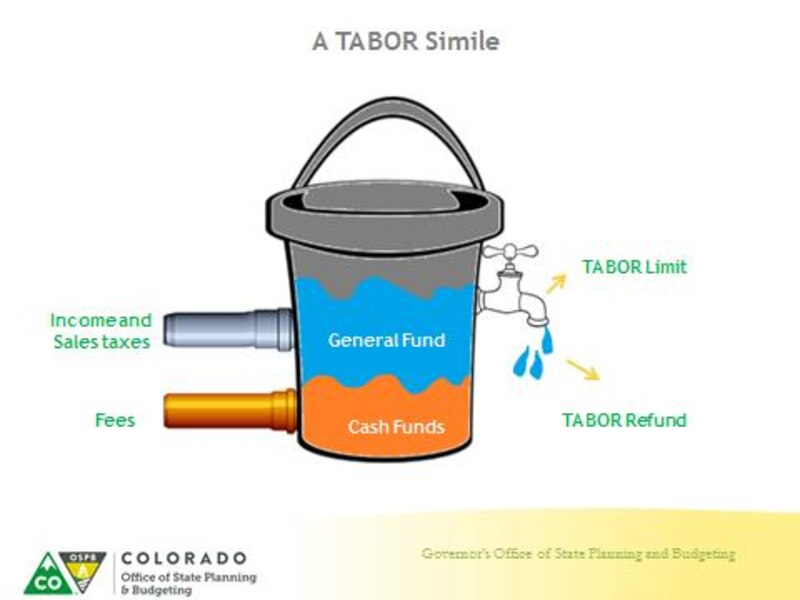

The controversy focuses on a funding mechanism called the hospital provider fee, which is used to pay Medicaid costs but which also counts toward the state revenue ceiling, forcing some tax revenue to be refunded rather than spent when revenue exceeds that limit.

The issue has been kicked around at the Capitol for a year. Democrats want to change the fee’s legal definition so it doesn’t count against the cap, freeing tax revenues for spending on state programs. Republicans say changing the fee will violate the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights unless voters approve the idea. TABOR is what set the state’s annual spending cap.

The debate was revived this week with introduction of two measures. House Bill 16-1420 would change the legal structure of the fee so that it does not count toward the revenue ceiling. House Bill 16-1421 would allocate any revenues freed up if the first measure passes.

There’s another big if – whether state revenues actually will grow enough by next September, when new revenue forecasts are issued, to generate the additional money for schools and colleges.

The proposed 2016-17 state budget already is $64 million under the ceiling. So for the second measure to take full effect, state revenues would have to grow by that amount plus another $156 million for the full transfers to public schools, colleges and universities to take place.

The $156 million would be used for four programs, transportation costs, refilling of two mineral tax funds, public schools and higher education.

Under that proposal, $40 million would go to reduce the current $831 million school funding shortfall, also known as the negative factor. Another $49.5 million would go to state colleges and universities to reduce tuition increases and increase financial aid.

There’s a final hurdle between schools and colleges and that money: Schools and colleges are third and fourth on a priority list. So, for instance, if there’s only $50 million in additional revenue, all of it would go the transportation.

HB 15-1420 passed the House Appropriations Committee Tuesday on 7-6 party-line vote. HB 16-1421 passed 8-5, with one Republican joining majority Democrats.

The panel spent more than three hours on the two bills, and testimony and member discussion highlighted the wide differences over the proposals.

The lead witness supporting the bill was Kelly Brough, president of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce.

Panels of witnesses representing business, public schools, higher education, hospitals and contractors followed to urge the committee pass HB 16-1420, whose primary House backer is Speaker Dickie Lee Hullinghorst, D-Boulder. Those interest groups are lobbying the issue heavily and even have launched a website to make their case.

No witnesses opposed the bill, but several Republican committee members raised familiar questions. While the issue is complicated, GOP objections boil down to the belief that legislative changes to the hospital fee would violate TABOR. They argue the hospital fee can be changed only by voters.

One prominent Republican, Attorney General Cynthia Coffman, has a different view. She issued a formal opinion last month concluding it’s perfectly constitutional for the legislature to change the provider fee.

If the bills pass the Democratic House, the real test will come in the Senate, where Republicans hold a one-vote majority. The Senate sponsor is Republican Sen. Larry Crowder of Alamosa. But the Senate GOP leadership have plenty of ways to kill the hospital fee bill before it reaches the floor, even if Crowder remains in support.

This illustration from the Office of State Planning and Budgeting is commonly circulated around the Capitol to illustrate how the hospital provider fee (part of the orange cash funds water) pushes total state revenues to the constitutional ceiling (represented by the faucet). Taxpayer refunds can be paid only from the tax-supported general fund, the blue water. So as fee revenue rises the amount of tax money available for spending is reduced.