Denver school officials agreed Monday to establish a centralized system for responding to complaints about school discipline, to better inform students facing expulsion or suspension of their rights, and to investigate concerns about schools underreporting discipline data.

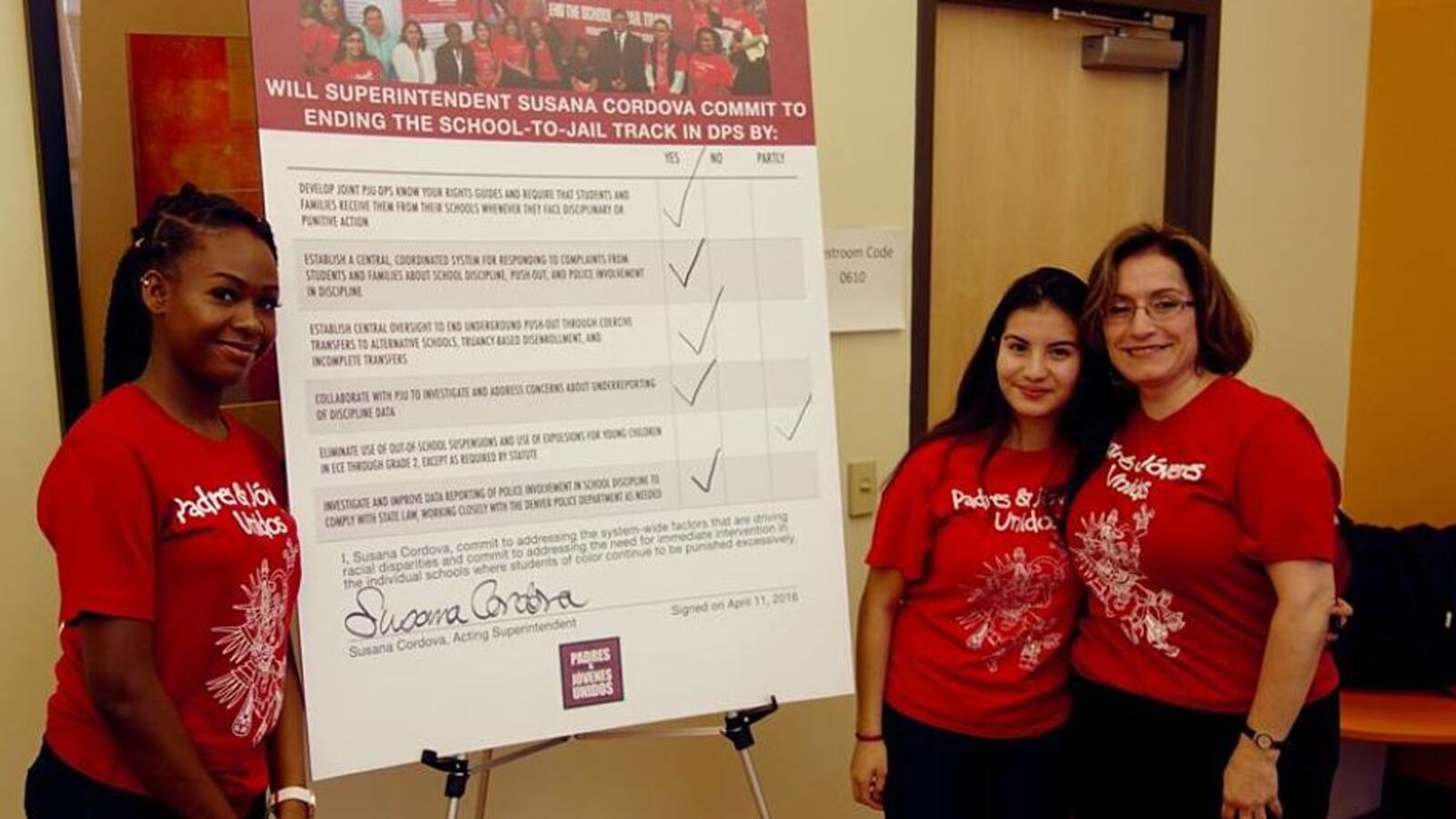

Standing in front of a crowd that included outspoken students and frustrated parents, acting Denver Public Schools superintendent Susana Cordova made those promises in response to a new report by advocacy organization Padres & Jovenes Unidos.

The group has worked for more than a decade to expose racial disparities in school discipline and end the “school-to-jail track,” pushing DPS to rewrite its discipline policy and forge an agreement with the police to restrict the role of officers in schools.

“We are deeply committed to this agenda,” Cordova said.

The report shows that while the number of suspensions and expulsions in DPS plummeted between the 2010-11 and 2014-15 school years, deep racial gaps persist. Students of color were 3.1 times as likely to be suspended or expelled in 2014-15 than their white peers, it says.

The report points to other problems, as well. The number of times a school requested a police officer get involved in a disciplinary or criminal matter stayed virtually flat in 2014-15, which the organization sees as a stagnation of progress after years of significant decreases.

The organization also raised concerns about what it calls underground pushout. Advocates said they’ve heard from families whose children were “kicked out” of their home schools and told to go to alternative schools without being informed about their right to refuse.

And while the number of suspensions is down, the organization is concerned about “off-the-books suspensions,” or parents being told to pick up their children early because they’re in trouble at school. The kids aren’t officially suspended and therefore not counted in the data.

This is the fifth year the organization has graded DPS on its discipline practices. It gave the district an overall grade of C+, which is better than last year when it got a C.

The report offers six recommended solutions. At Monday’s meeting at a southwest Denver public housing community center, Cordova agreed to five of them, including to collaborate with the organization to address potential underreporting of discipline numbers. Advocates suspect that not all schools are collecting data in the same way.

“Without accurate data, we can’t understand where there are problems,” said student Alanis Hernandez.

Cordova only partly agreed to eliminate the use of expulsions and out-of-school suspensions for kids in preschool through second grade. Cordova explained that while the district is committed to doing so for the district’s youngest children — DPS suspended just 10 preschoolers last year and didn’t expel any, she said — it can’t make the same pledge for first and second graders.

During the event, Cordova wore a red Padres y Jovenes Unidos T-shirt and listened as students shared personal stories and read from the report. There was Jaquikeyah Fields, who introduced herself as “pre-choreographer, not pre-prison.” And Jhovani Becerra, who said he was “pre-computer science, not pre-prison.”

Arianna Perea, “pre-film director, not pre-prison,” spoke of how she was handcuffed by her school’s police officer when she was 12 years old. A classmate had reported that Perea threatened her, a claim she said was untrue.

Perea said she was eventually let go, but the experience led her to dislike school and struggle for several years. Now a student at North High School, Perea said she’s looking forward to graduating and going to college. Students need to know their rights, she said.

“When they come at you with handcuffs, knowing your rights means that those cuffs can come off,” she said.

Several Spanish-speaking mothers spoke, as well. They told stories of their children being suspended from preschool, of being called in the middle of the day to pick up older kids for alleged misbehavior and of their kids being sent home for days while the school decided to whether to expel them. Cordova, who is bilingual, addressed them in Spanish.

“I am a mother as well,” she said. Listening to their stories hurt her deeply, Cordova said.

“Your children are my children,” she said, adding that “it’s important we fight together.”