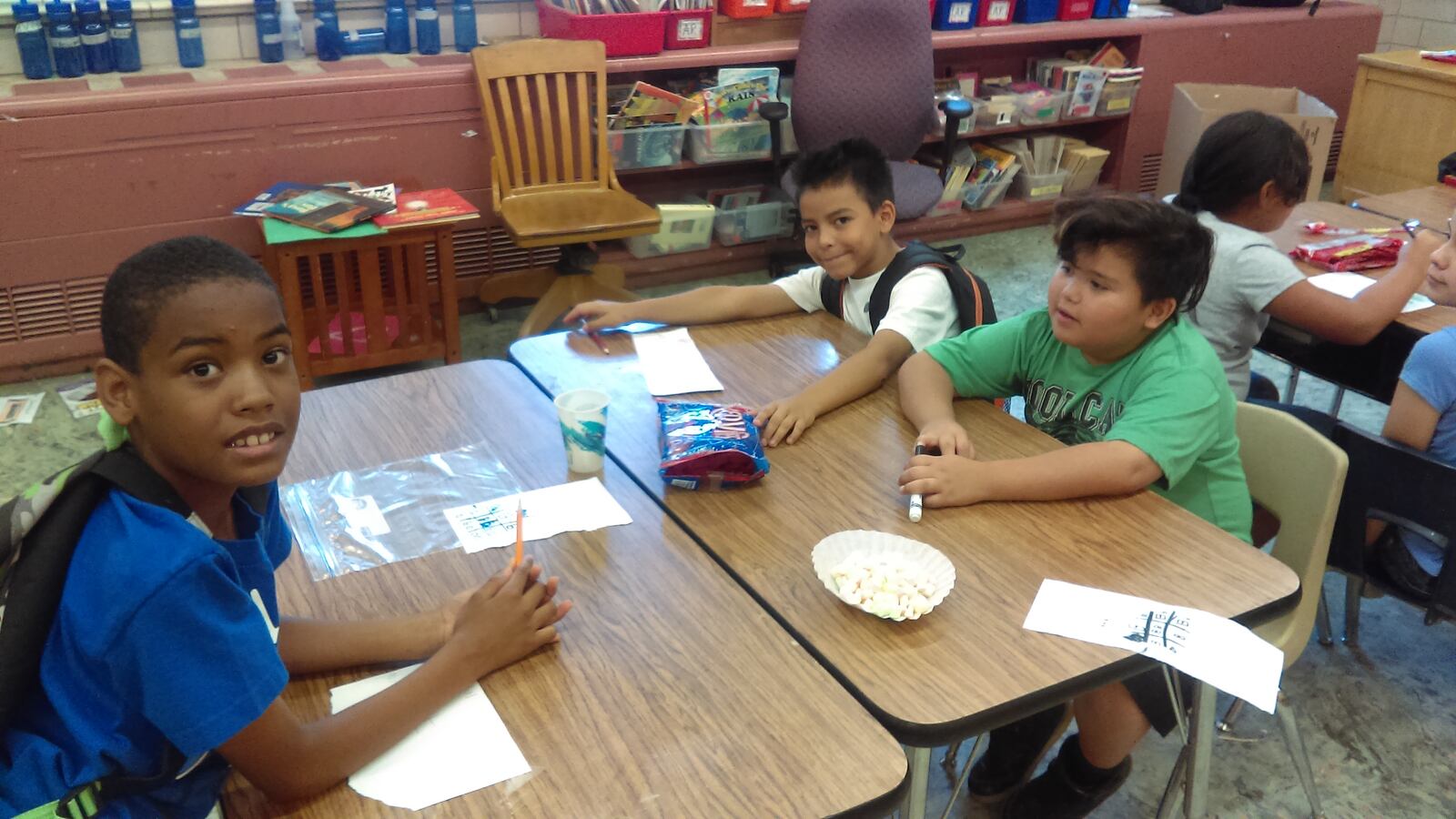

At an eight-week elementary school summer camp run by Denver Public Schools, licorice and marshmallows are part of the program.

In one classroom last week, students twisted red licorice into helixes and wedged marshmallows stuck on toothpicks between them — a rough approximation of the structure of DNA. Sara Ulricksen, a DPS program specialist, described it as “disguised learning.”

“They think they’re playing with candy,” Ulricksen said this week at Cowell Elementary, site of the camp. “But they are really learning about DNA and how blood runs through the body.”

Dubbed Summer SLAM — the acronym stands for science, literacy, art and movement — the program is part of a broader movement nationally to arrest the so-called summer slide, when students left to their own devices lose what they’ve learned and fall behind.

“Our summer is a wondrous time to learn,” DPS Superintendent Tom Boasberg said during a visit to the camp last week.

The camp, in its fourth year, is free and open to all Denver Public Schools elementary students regardless of income. It is paid for by 2012’s voter-approved Measure 2A, which allowed Denver to retain and spend $68 million in tax revenue it otherwise would have been required to refund.

Most of the 150 students enrolled in this year’s camp are Latino, reflecting the location of the school in southwest Denver. The camp has a capacity of 180 students, officials said.

Research shows that children from poorer families fall behind in the summer as their more affluent peers attend camps or get support at home, setting them up for success in the fall.

Laura Johnson, spokeswoman for the National Summer Learning Association, which works with local organizations and school districts to promote effective programs, said the impact of falling behind on learning in the summer can be long-lasting.

“[The summer slide] has a cumulative effect, especially for low-income children,” she said.

According to the association, fifth-grade students with cumulative years of summer learning loss could be as many as three years behind their peers.

Finding affordable, accessible summer enrichment programs is another challenge, said Matthew Boulay, founder of the National Summer Learning Association.

“The formal camps are the gold standard,” he said. “They tend to have limitations on things like space or availability and price.”

Other states and cities have invested in programs designed to arrest the summer slide, as well.

Grant money from the Tennessee Department of Education paid for summer programming that has been credited for either raising or maintaining the participating children’s reading levels.

New York City students who spent more time on iPads as part of a summer program tended to improve their reading skills, research showed.

In Denver, staff at Cowell Elementary School have found that students who attend the camp are on par with or ahead of their classmates once school resumes, Ulricksen said.

Regardless of the approach, Boulay, of the National Summer Learning Association, said the key to avoiding the summer slide is keeping kids engaged in learning. For instance, you can curtail the amount of time kids devote to reading — just keep them reading.

“You can do it different ways,” he said. “It can be more relaxed [once school ends]. But keeping those same habits from the school year is really important.”