The new preschool in northeast Denver is nestled in one wing of a sleek modern building with neat rows of peas, turnips, and spinach flourishing in a huge garden out front.

In gentrifying Denver, the scene is familiar—sparkling new construction rising up from the site of a razed shopping plaza.

But the story of this preschool and the new Mental Health Center of Denver facility in which it sits isn’t about satisfying the demands of the city’s new arrivals. If anything it’s the opposite—an effort to meet the needs of existing residents who have long been overlooked and underserved.

They are the families—nearly half of them African-American and many low-income—that call Northeast Park Hill home.

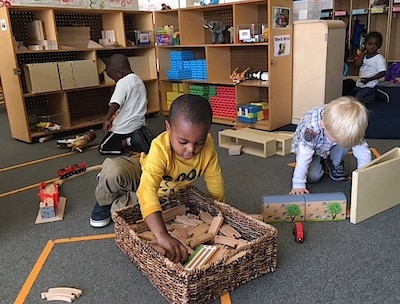

Opened in January, the Sewall Child Development Center at the Dahlia Campus is taking an approach its leaders say is unique in Denver and perhaps the nation: providing one neighborhood in need with a high-quality full-day preschool that serves all kids together, including those with challenging behavior and other special needs.

Although a small number of preschool programs in Colorado do offer this type of inclusive program, they usually draw students from a wide area.

At the same time, neighborhood-based preschool programs often exclude, counsel out or expel challenging children who may be given to explosive tantrums, aggression or chronic crying.

“A lot of preschools just place a huge emphasis on obeying, complying with adult requests,” said Christine Krall, who heads the Dahlia campus program. “We get kids who (have been) kicked out of three preschools.”

The center also serves kids who previously attended specialized programs far outside northeast Park Hill. While the programs may have worked educationally, they didn’t work geographically — forcing parents to miss school meetings or family nights and weakening the bonds between neighborhood families whose children with special needs were spread out across Denver.

“We want kids to go to school where they live,” Krall said.

Heated conversations

Officials from the Mental Health Center of Denver began considering building a new community facility on the site of the former Dahlia Shopping Center in 2013.

In a series of community conversations that lasted more than a year, local residents were plenty skeptical. They worried about the stigma of a mental health center in the neighborhood. What they wanted were places to buy healthy food and more early childhood choices, especially for kids with special needs.

As talk turned to the possibility of including a preschool in the new space, they feared they’d lose the preschool spots to more affluent residents who live in the Stapleton redevelopment farther east.

Lydia Prado, vice president of child and family services at the Mental Health Center of Denver, said community members painted a picture of the future they predicted.

She relayed what they told her: “There are a lot of people in Stapleton who work downtown. They’re going to come down (Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd.). They’re going to drop their child off and they’re going to go to work. They’re going to be able to pay and you’re going to take them.”

But Prado didn’t want that scenario either. So she and the residents made a deal. When publicizing the new preschool, mailers would be sent only to residents in the 80207 zip code, which covers a large swath of northeast Park Hill.

The new complex, called the Dahlia Campus for Health and Well-Being, opened in January. Besides the preschool, it offers an array of health and mental health services and includes a vegetable garden, greenhouses and a fish-farming operation.

Sewell Child Development Center, a longtime Denver nonprofit specializing in inclusive education, runs the preschool. Denver Public Schools, which provides funding for some of the preschool slots, and the mental health center are both partners in the program.

It’s not a simple or cheap program, which explains why there aren’t more centers like it. It requires a complicated mix of state, school district, city and private funding to pay for the extra staff needed to maintain high adult-child ratios, including a raft of specialists such as speech therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists and social workers.

Currently, about a dozen employees staff three preschool rooms at Dahlia. Together they have of 45 slots—most filled by children from the neighborhood who attend for free or pay a small portion of the cost. A fourth classroom will open eventually.

“I think it’s great to have an alternative that’s inclusive—that has that intensity of mental health support, said Cheryl Caldwell, director of early childhood education for Denver Public Schools. “It’s good for families and kids.”

Opening doors for parents

Charella Hysten enrolled her 2-year-old son, Jair, at the Dahlia campus preschool about a month ago on the advice of a special education advocate.

Landing a spot there has allowed her son to get speech therapy consistently, where previously it was impossible. Bringing therapists to the house or meeting them in libraries set the stage for explosive outbursts from her 10-year-old twins, who have severe behavioral issues.

The preschool slot, along with inpatient treatment for her twins elsewhere, also allowed Hysten to start a job as a cook at a Qdoba restaurant after eight years at home.

“It allows me to make a paycheck…and possibly boost my self-esteem because I’ve been in the house feeling like nothing,” she said.

Hysten knows Jair likes his time at the preschool because of how easily he parts from her each day.

“He tells me ‘Bye,’” she said. “As a mother of seven, when you drop off your child and he says ‘Bye,’ that’s a good thing.”

Administrators at Sewell and the Mental Health Center of Denver say for many preschool families at the Dahlia campus, the program gives them respite from the raised eyebrows and instant judgement they face at restaurants, stores or elsewhere when their children act out.

“It’s not embarrassing to be here,” said Krall.

A twist on the Sewall model

Sewall runs 10 preschool sites around Denver, all of them with a mixture of typically developing kids and kids with special needs. Usually, about one-third of the students have a specific diagnosis such as autism.

At the Dahlia campus program, it’s a little different. There are fewer kids with diagnosable conditions and more kids with challenging behavior due to trauma such as abuse, chaotic living conditions or other factors. That makeup reflects the needs in the neighborhood.

Take teacher Kindal Matson’s classroom. Only two of nine students have a diagnosis, but four additional students need extra help regulating volatile emotions. One little girl has trouble when it gets too noisy, throwing things off shelves, running away or climbing on tables.

That’s part of the reason there are two teachers plus an additional staff member—a therapist or special education teacher—for every 15 kids. The three, all trained to teach social and emotional skills proactively and avoid punishing kids, work as a team with all the children.

“Each day a specialist comes in and works right alongside us,” Matson said. “They change diapers just as we do.”

The work can be draining at times. At a recent debrief with a social worker, Matson’s teaching team talked about coping with the daily ups and downs.

“You’re a sponge and you’re absorbing all these children’s needs and their disregulation, and you might have gotten bit three times today,” she said.

Still, Matson finds the work rewarding and is happy she moved to the Dahlia campus preschool in June after a stint at a more traditional preschool. The program’s emphasis on including all kinds of kids was what appealed most to her.

It also comes with benefits for both children with special needs and their typically developing peers, she said.

The girl who struggles with noise almost always manages to keep her emotions under control when she plays with a certain even-keel friend. Meanwhile, the mother of that friend reported to Matson that her daughter has grown more patient with her little brother since she came to the preschool.

Acknowledged at last

With seven months since the Dahlia campus preschool opened, there’s a sense that the puzzle pieces are falling into place.

There’s still an alphabet soup of funding sources to contend with, some empty slots to fill and new hires to make. But amidst such challenges are moments like the one Prado experienced after the center opened.

She said the mother of a little girl with special needs approached her one morning to say thank you. Tearing up, the woman confided that she’d long felt invisible.

She told Prado, “No one has seen me before and no one has seen my daughter…You have seen us. I never thought that would happen.”