Olga Montellano is kind, patient and doesn’t flinch when small children shout excitedly in her face.

On a recent afternoon, her calm demeanor was on display as she watched over her 3-year-old daughter and her next-door neighbor’s 3-year-old son as they frolicked on her front lawn in north Denver’s Elyria-Swansea neighborhood.

When the ponytailed mother of four heard what sounded like gunshots a street over, she ushered the children onto the porch, past a giant reading nook she’d crafted from cardboard, and into the house.

Montellano has been taking care of kids in her home for five years, ever since her next-door neighbor got a job at a factory and needed someone to watch her older child, now a kindergartener. In late November, Montellano added a 2-year-old boy to the mix, the son of a friend who’d just landed an office-cleaning job.

This kind of informal, mostly unregulated child care is a lifesaver in Elyria-Swansea, where train yards, Interstate 70 and large industrial plots share space with residential pockets that, as of now, are home to many poor and working-class families.

Licensed child care — particularly for children 3 and younger — is hard to come by here. The problem is so pronounced, the neighborhood has won an unwelcome designation: Child care desert. Put simply, it’s a place where the number of small children far exceeds the number of licensed child care slots.

But a slate of recent efforts could help Elyria-Swansea shed the label — and hold implications for other communities grappling with the problem.

The initiatives, which use both public and private money, include training for informal providers like Montellano, efforts to better match home-based child care slots with families and attempts to bring new child care centers to the area.

The idea is to ease the child care scramble that plagues many working parents in the largely Hispanic neighborhood and help set up young kids for future academic success. Currently, more than half of neighborhood children — many of them English learners — aren’t reading proficiently by the end of third grade.

Together, the projects represent an ambitious undertaking that could bring much-needed attention to a long-neglected neighborhood. But they’re also separate efforts with different leaders, missions and geographic reach — all unfolding as locals brace for big changes in the neighborhood.

On the horizon are a massive expansion of Interstate 70, which splits the neighborhood, and a billion-dollar overhaul of the National Western Stock Show complex. And as Denver’s breakneck growth continues, the neighborhood is showing signs of gentrification.

To those invested in transforming child care in this Denver neighborhood and similar urban areas across the country, all the changes raise an uncomfortable question: Will the families who need help still be around when the work is done?

“That’s a fear that we all have,” said Nicole Riehl, director of programs and development at Denver’s Early Childhood Council, one of many partners in an initiative called United Neighborhoods doing work in Elyria-Swansea.

Scope of the problem

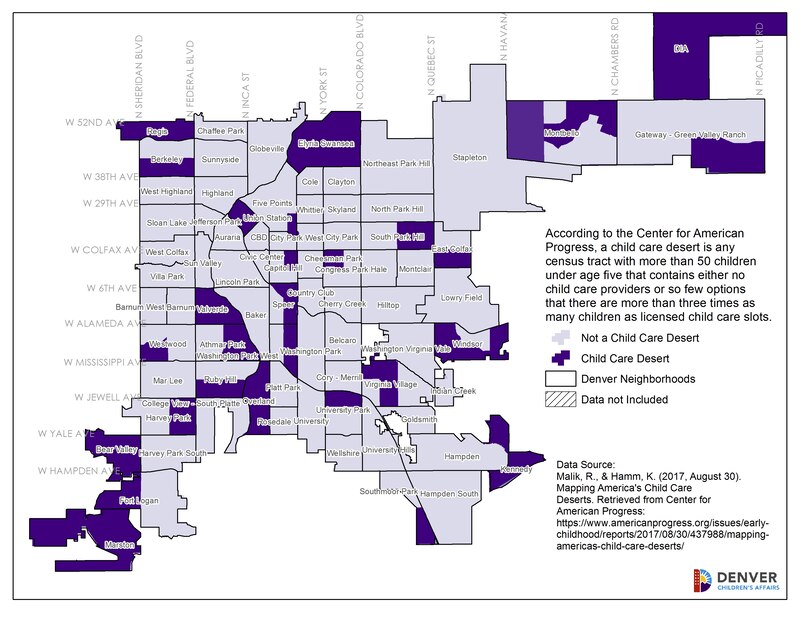

Nine of Denver’s 78 neighborhoods, including Elyria-Swansea, are classified as child care deserts, according to data from a recent Center for American Progress report. Parts of more than a dozen other neighborhoods also earn that designation.

The report found that half of the people in the 22 states it examined live in a child care desert, which it defines as neighborhoods or small towns with either no child care options or so few that there are more than three children for every licensed child care slot.

In Elyria-Swansea, parents cope in various ways. Some rely on nearby relatives or neighbors to watch their children. Others, if they have cars, drive their kids to child care centers or preschool programs outside the neighborhood. Some, fearing child care will eat up their whole paycheck, leave the workforce altogether to stay home with their kids.

Martina Meléndez, a single mother of four who lives in the neighborhood, illustrates the extent to which families cobble together care when affordable, flexible options aren’t available.

She works at night so she can be home during the day to handle school and preschool pick-ups and drop-offs for her younger three children. When she heads to her office-cleaning job, she enlists her college-age son to watch his siblings. On the weekends, when she waitresses full-time and her oldest son goes to his part-time job, she pays a babysitter $200 to stay at her house with the kids.

Meléndez worries about the toll the arrangement takes on her eldest son.

“I would like to be able to take care of my kids myself so that he doesn’t have so much pressure,” she said. “I know he’s going to have to concentrate more on school.”

Meléndez’s experience isn’t unique, but it is a reminder that market forces alone don’t ensure an adequate supply of child care in many communities.

That’s why quality child care needs to be understood as a public good — one that requires the same kind of public investment that pays for roads, bridges and schools, said Rasheed Malik, co-author of the Center for American Progress report.

“There’s starting to be discussions with state legislators and people on (Capitol) Hill in D.C. who are beginning to take up that mindset,” he said.

According to the report, 30 percent of Colorado residents live in child care deserts, but the problem is more acute in some communities — including those with higher Hispanic populations.

That’s the case in Elyria-Swansea, where more than 60 percent of residents are Hispanic, according to census estimates. The same is true in several other Denver neighborhoods classified wholly or partly as child care deserts, including Valverde, Athmar Park and Ruby Hill.

No local space

In Elyria-Swansea, a variety of factors contribute to the lack of child care — ranging from poverty to the neighborhood’s industrial roots. Amidst its train yards, warehouses and marijuana grow houses, there’s little suitable space for commercial child care — a high-cost, low-margin business.

Only Swansea Elementary School and a tiny nearby Head Start program offer formal child care in the neighborhood — a total of 81 full-day seats, mostly for 4-year-olds.

Even the federal government has picked up on the problem — earmarking the ZIP code for special consideration in grant awards for certain child care slots.

“Our challenge is facilities out there,” said Lance Vieira, chief operating officer of Rocky Mountain Service Employment Redevelopment, which runs the Head Start program in Elyria-Swansea.

Some local families send their kids to another Head Start center three miles away in the Sunnyside neighborhood. Special busing was provided for the youngsters through last year, but that ceased for a variety of reasons, including because the program switched from half- to full-day.

In a bid to help satisfy the demand for child care, Focus Points Family Resource Center, a longtime nonprofit serving families in Elyria-Swansea and Globeville, used grant money to open up a 30-seat preschool in the fall of 2016. With no space available in the two neighborhoods, leaders settled on a facility in the nearby Cole neighborhood.

Quality varies

Yadira Sanchez, a mother of three in Elyria-Swansea, knows what it’s like to struggle with child care. She still remembers sending her oldest child, Ruben, now 17, to a neighbor’s house when he was a little boy and she was working as a home health aide.

Culturally, she and her neighbor had a lot in common, and she felt confident Ruben would never be abused. Still, the boy spent most of his time on the couch and was regularly asked to share the meals Sanchez packed for him with the neighbor’s young daughter. The woman, who sometimes watched soap operas during the day, was anxious about the children getting hurt and discouraged active play.

The kind of informal care Sanchez used for Ruben — often called family, friend and neighbor care — is common in Elyria-Swansea and many other communities. Often, parents like it because they know the caregiver well, hours are flexible and it’s usually inexpensive or free.

Still, such unlicensed care is mostly unregulated by the state and quality varies widely.

Sanchez’s neighbor, who’d eventually added Ruben’s sister and a couple other children to her child care roster, stopped offering care after a few years.

“She felt like, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing, maybe I shouldn’t be doing it,’” Sanchez said.

From there, Sanchez tried a licensed home and two licensed centers outside the neighborhood but didn’t like those options, either. At two of them, the providers were cold, strict and the kids were often in trouble.

Sanchez wishes there was a child care center in the neighborhood.

Nothing fancy, she said. “Just a safe place … with people who actually love to work with kids.”

Rosemary Alfaro, who lives in Elyria-Swansea and works as a clerk for a home visiting program, yearns for the same kind of thing.

Over the years, she’s made various child care arrangements for her children. Her husband’s aunt helped out for awhile and the two older girls attended Head Start in the Sunnyside neighborhood and later the Highland neighborhood — a short drive to the west.

Today, her 3-year-old son attends morning preschool at the Focus Points center in the Cole neighborhood and her mother-in-law takes care of him and another youngster in the afternoons.

“She is my right-hand woman,” Alfaro said. “If I didn’t have her, I wouldn’t know what to do.”

Expanding the pipeline

One day last summer, two-dozen Spanish-speaking women practiced first aid and CPR on rubber dummies at a Catholic church in north Denver. An instructor in pointy cowboy boots walked them through the proper responses to various emergencies — discovering an unconscious child on the ground or handling a seizure without knowing the child’s medical history.

Olga Montellano — the caregiver who ushered the children inside after hearing the gunshots — was there. So was Dolores Alfaro, Rosemary’s mother-in-law.

The four-hour session was part of an intensive course for family, friend and neighbor providers called Providers Advancing Student Outcomes, or PASO.

The initiative is just one part of United Neighborhoods, a Mile High United Way project focused on education, housing, health and workforce development in Elyria-Swansea and neighboring Globeville. It began last year and is expected to last three to five years.

The course leads to a common entry-level child care credential and represents a key strategy in the United Neighborhoods plan to address the problem of child care deserts.

The Colorado Statewide Parent Coalition, one of several partners in the United Neighborhoods work, has run PASO classes in several Front Range communities for years, often enrolling mostly undocumented immigrants and paying for the program with private funds.

The course in Elyria-Swansea is a bit different. The City of Denver’s Office of Economic Development — another United Neighborhoods partner — kicked in $130,000 to cover the cost of 14 participants, all of whom are legally in the United States.

City officials say the investment was a chance to help residents climb up the first rungs of the career ladder and improve child care quality at the same time.

Once PASO ends in mid-December, more than $5,000 in federal funding will be used to shepherd some participants through the arduous licensing process that will allow them to offer state-sanctioned child care in their homes. Leaders at Denver’s Early Childhood Council, which will provide that assistance, say they’ll create eight new Early Head Start slots for children birth to 3 in the 80216 ZIP code by next fall.

Other initiatives unfolding now or launching in the near future could eventually help boost child care offerings in Elyria-Swansea, too.

One, funded partially by Gary Community Investments and set to start in spring of 2018, relies on a nonprofit called WorkLife Partnership. The group operates across Colorado, charging employers a membership fee to get help with services — such as child care or housing — that help employees stay on the job.

Liddy Romero, executive director of WorkLife Partnership, said to increase child care along I-70, where soon hundreds of construction workers and other kinds of employees will be needed, the group will award $5,000 mini-grants to licensed in-home providers. The idea is to help them buy new curricula or equipment, and figure out how to offer more slots or expand into overnight care.

WorkLife Partnership is also partnering with the national online marketplace Care.com to ensure those providers — once they expand their capacity or hours — get efficiently matched with families that need child care.

Using money from another source, Romero said the group is already working with 17 in-home providers along I-70. None of the 17 are in Elyria-Swansea or Globeville, but providers from both neighborhoods, possibly some who are not yet licensed, could be included in the future.

Liliana Flores Amaro, an Elyria-Swansea resident and community activist, said with some residents leery of outsiders pushing in solutions, it’s important for leaders of all the projects underway or planned to avoid a “deficit mindset.”

They should approach the work “really honoring and respecting the experience and knowledge of child development and child-rearing that is in this neighborhood,” she said.

Changing city, changing neighborhood

Residents and civic leaders all see signs that gentrification is coming to Elyria-Swansea — and sending residents to Adams County, Aurora and Edgewater.

For leaders at Focus Points, one indicator was the gradual disappearance of waitlists for parenting programs that were once over-subscribed. At the Valdez-Perry library branch, it’s near-daily goodbyes staff bid to patrons who are moving out of the area.

And, of course, there’s skyrocketing real estate prices.

“The reality is these families will be offered so much money for their houses they’re not going to stay,” said Vieira, of Rocky Mountain Service Employment Redevelopment. “It’s going explode in Globeville and (Elyria) Swansea will be very close behind.”

So what will come of efforts to fix the child care desert if the families — and the kids — move away? No one expects all current residents to leave, but the demographics will surely change. Some observers expect fewer large families and an influx of middle-class residents.

One check on gentrification could be new affordable housing planned for a large new development to be built on a six-acre parcel at the corner of 48th Avenue and Race Street. Leaders at the Urban Land Conservancy, which owns the land, say there will be hundreds of affordable housing units included, but the exact number will be determined when a developer is chosen in early 2018. The development will include space for local nonprofits at below-market lease rates. The first phase of construction could start in 2019, with completion four to five years later.

Sheridan Castro, the interim executive director of Focus Points, said the group will apply for some of that space for a childcare facility there. The idea is to move the organization’s preschool in the Cole neighborhood to the new development and add care for infants and toddlers.

“It would be an economic opportunity as well for members of our community and our staff who have been working toward becoming certified early childhood educators,” Castro said.

Christi Smith, the conservancy’s operations and communications director, said the need for child care in the neighborhood is well-known, but there’s also interest in using the nonprofit space for a medical clinic, a fresh food market or job training. As with the affordable housing units, the developer will make the final decision, she said.

But even if the new development does include a child care center, some observers expect families who can afford to pay for the care will scoop up many slots.

All the changes bring both hope and uncertainty for long-time residents like Olga Montellano.

She already believes the PASO program has made her a better caregiver. She gets the children in her care outside more and has learned skills and activities to help get her neighbor’s 3-year-old son, who used to be silent, talking.

But whether she stays in the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood is an open question. Her landlord has raised the rent, but not much, she said. She would like to buy a home, but homes that used to be affordable and small are now unaffordable and small.

“My preference would be to stay here because I’ve already lived here 15 years,” she said. “I don’t know … it seems strange to leave.”