Colorado’s State Board of Education faced an unprecedented decision.

A neighborhood school serving mostly black and Latino students had been failing for too long. Despite an all-out effort to boost test scores — even the mayor tutored kids on the weekends — the needle hadn’t moved enough. State law required the board to wrest the school from its district and hand it over to a charter operator.

The year was 2004, and the school was Cole Middle School in northeast Denver.

Just three tumultuous years later, the state was handing the campus back to the district with few of its problems solved.

What happened at Cole offers a cautionary tale as Colorado begins an even grander experiment — trying to turn around 12 struggling schools and five school districts.

Lawmakers have already worked to learn from their missteps at Cole. But even after they revamped the state law about schools that fail to improve, gray areas remain, and local communities are wary of state overreach.

As the state board prepares to take action this week, Chalkbeat spoke with members of the board that intervened at Cole — and with others in the school community at the time. Their reflections offer a new look at a little explored episode in Colorado education policy — one that merits more attention as a new cast of characters takes on an even bigger challenge.

PART I “It was like trying to put together a puzzle and you’re missing 50 pieces of the puzzle.”

Four years before the state’s attempt to to save Cole, Nathan Grover joined the staff as a science teacher. Cole was his first teaching job, and he quickly realized the school was not like the ones he attended in Wisconsin.

NATHAN GROVER: “In the classroom, I was the minority. That was a first for me. It was a paradigm shift. We might have had four African-American kids attend my school.”

Just about every student who attended Cole was black or Latino. Nearly 100 percent of the 330 students were poor enough to qualify for federally subsidized lunches.

Socioeconomic challenges in the historically black neighborhood spilled into the classroom, as often is the case at poor schools across the country.

GROVER: “Our students had difficulties and struggles that were beyond the classroom. Some had to put food on the table. Others had to look after their younger siblings. There were socioeconomic needs that Cole couldn’t provide for. So school wasn’t always a priority. And sometimes it was reflected in how students learned.”

Patty Lawless was a community organizer for the Metro Organization for People, now known as Together Colorado. She also lived in the neighborhood with a son about to enter middle school.

PATTY LAWLESS: “Cole had a reputation. And I made a conscious decision not to send him there. We knew it wasn’t performing well. If people could, they were choosing not to go there. There was a lot of concern around drugs and fighting and discipline.”

The school had a hard time keeping teachers and principals. By 2004, Grover was one of the most senior members of the school’s teaching staff, even though he had been there just four years. He had outlasted four different principals. Students in the Cole neighborhood also moved in and out frequently, making it hard to bring any continuity to classrooms.

GROVER: “It was like trying to put together a puzzle and you’re missing 50 pieces of the puzzle.”

As Grover, who is now an assistant principal at East High School in Denver, was learning how to survive as a teacher in a high-needs school, lawmakers were crafting the state’s first school accountability system.

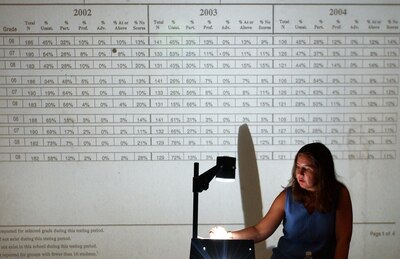

The law, known as Senate Bill 186, did two main things. First, it created school report cards that were supposed to measure school quality for parents, business leaders, and taxpayers. The law also said that if a school failed three years in a row, the state would select a charter operator to take it over.

The bill was written in 2000, when school accountability systems, which evaluate schools based on student test scores, were coming into vogue across the U.S. It was championed by then-Gov. Bill Owens, a Republican and ardent supporter of charter schools. The day he signed the bill into law, he called it “a bold new step” to improve communities and “a great day for Colorado’s children and a great day for our public schools.”

Cole and a handful of other Denver schools were tagged as failing in the first year of the new system.

GROVER: “As soon as that happened, all eyes were on us.”

In an effort to turn things around on their own, Denver Public Schools hired first-year principal Nicole Veltzé to take over Cole. Veltzé is now an assistant dean at the Relay Graduate School of Education.

NICOLE VELTZE: “When I got there, the school was crumbling. The academic achievement was the lowest I had seen anywhere. It was everything you define as the antithesis of what you want in a school.”

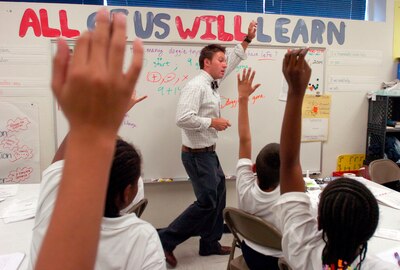

The entire city soon rallied behind Veltzé and Cole in an effort to “Beat the CSAP.” Elected officials — including Gov. John Hickenlooper, then Denver’s mayor — and business leaders began helping staff tutor students on Saturdays.

VELTZE: “We had amazing students. They were very resilient. The kids quickly turned around. They wanted more for their education. We had 75 percent of kids attend tutoring every Saturday to try and make a difference. Once they realized the community was rallying behind them, and we put supports in place, those kids rose to the expectation.”

One morning in early August 2004, Veltzé received a call from district officials. Cole didn’t make it. The school’s fate was sealed: Beginning the following year, it would be run by a charter operator, not Denver Public Schools.

VELTZE: “It was the most empty feeling I’ve ever had. There was nothing we could do. It was the law. It didn’t matter how much progress we made. It didn’t matter that now-Gov. Hickenlooper was there tutoring every Saturday. It was the law. There was no other recourse.”

State board members knew that they would be tasked by law with the duty of selecting a charter school to take over Cole. But that doesn’t mean they were prepared for what was ahead.

PART II

“There was no process. There was just me and my colleagues.”

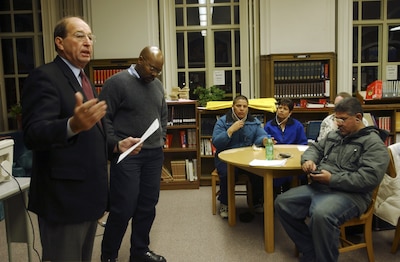

Aurora Public Schools Superintendent Rico Munn served on the state board at the time, representing Denver. Even though state law clearly defined the state board’s role in intervening when schools persistently struggled, Munn said the board had been occupied with other matters. That left the board and the education department little time to figure out its next move for Cole.

On top of that, the state had never sought or evaluated charter school applications before.

RICO MUNN: “There was no process (to solicit or choose a charter operator). There was no evaluation framework. There was no team to evaluate what was working and what was not working. There was just me and my colleagues.”

While the state board scrambled, Cole parents and community members grew frustrated. They felt the school had begun to turn the tide, and they felt the state was stepping in too soon.

LAWLESS: “There was some anger around the state coming in and saying, ‘OK, you’re done.'”

Veltzé tried to keep the school community calm and engaged in learning.

VELTZE: “We had to continue to compliment the students and teachers on the work they did. We kept the focus, especially for students. We told them they needed to be ready for high school. We told them we were going to find the best school for them to continue to work in. I continued to work with every single teacher to make sure they transitioned to their next position. Some teachers were afraid they were going to be labeled as failing. And that wasn’t the case. We had to work one-to-one to keep the morale up.”

As the summer turned to fall, the state board had four charter school applications to choose from, including one from the Denver-based parent advocacy organization Padres & Jóvenes Unidos and another from the national charter network KIPP. The other groups that applied were Mosaic and Edison, both for-profit national networks that operated schools in Denver.

Padres had never operated a charter school before. But it had interest in replicating a successful charter school in Pueblo. KIPP had just opened its first charter school in Denver.

Steve Mancini is the public affairs director for the KIPP Foundation. He spent time in Denver during the Cole debate.

STEVE MANCINI: “KIPP was encouraged by school officials and board members to apply. We wouldn’t have known about the state’s process if they hadn’t. At that point, we were only operating middle schools and had never tried a turnaround effort before.”

As the state board evaluated the charter applications, Lawless’s organization fought to make sure community voices were heard on a committee that would help the state board choose which charter operator to select.

LAWLESS: “We said, “If you’re going to do this, then we’re going to be involved.” We got two parent leaders onto the official state committee. And we trained them to be able to participate in that effectively. We also asked each applicant to present to our families on two different evenings. We created a rubric with a national consultant to help parents evaluate each school.”

One thing soon became clear: None of the options was exactly what Denver needed.

Former state Sen. Evie Hudak served on the state board at the time.

EVIE HUDAK: “We were very frustrated on the state board because no one proposed a middle school. KIPP proposed a 5-8 configuration. One applicant proposed a K-12, one proposed a 6-12 and another proposed a K-8. Simultaneously, Denver was converting all of its elementary schools in the area to K-8s. We were wondering if Cole would end up having any students.”

PART III “The whole thing — it was a disaster.”

Almost four months after the state board announced it would hand Cole over to a charter school, the board reached a decision. The board voted unanimously to sign the school over to the KIPP Foundation, which got its start in Houston and then New York.

Board members worried about holes in KIPP’s plans. But they also thought KIPP offered Cole the best shot of success. It offered the closest thing to a middle school for the neighborhood and had a huge national organization behind it.

The decision was based on a compromise. KIPP, known for pioneering the “no excuses” charter school movement defined by high expectations and strict discipline codes, would run a “transformation school.” In an unusual move, the charter would phase out one grade level at a time. Then, in 2007 after all the existing students had left for high school, it would begin a new school with only fifth graders. Then each year they’d add another class of students.

Community members were not happy. They feared Cole’s existing students would be lost while KIPP focused on opening a more robust school later.

Many parents had hoped Edison, which operated a school near by, could take over the school. But state board members worried the school’s state test scores were not high enough.

HUDAK: “After we picked KIPP, some of the seventh graders came and cried and said, “We don’t want to go to a school that’s like a jail.” They felt they had no choice. The whole thing — it was a disaster.”

Because the state board does not have chartering authority, DPS was required to work with KIPP to iron out details of the handoff. That process stretched on for months.

MANCINI: “DPS approved our contract in the spring of 2005. And we opened to existing seventh and eighth graders in July of 2005. This gave us a short window of opportunity to engage.”

PART IV “We were trying to do two different schools.”

With the decision to hand over Cole behind them, frustrated state board members went to lawmakers to ask for more flexibility in how they hold schools and districts accountable. Specifically, they wanted failing schools to have the option to submit their own school improvement plans for board approval.

MUNN: “It wasn’t so much that I was opposed to Cole being turned over to a charter. I was opposed to there being only one option (in the law). To say the change has to be a charter seems to predestine that a charter is the end-all, be-all. We know it’s not a magic bullet.”

Lawmakers listened and changed the law. Going forward, schools would be able to submit their own plans and remain under district control.

By then, the process to hand over Cole was already underway. And it was not going well.

As KIPP took over and began its first turnaround effort ever, student enrollment dropped. For a number of reasons, there were three different principals in the first five months the school was under KIPP’s control. And it could not find a principal to lead the second phase of takeover.

MANCINI: “We were trying to do two different schools. But we never found the leader to start the new school. We have a very selective process and no one who applied met the bar. If there was an issue at Cole, the principal was immediately interviewed by two newspapers. That made people less likely to step up and lead the second school. You’d have to walk in and on day one know the media was standing next to you. Whatever was happening at the school was on the front page all the time.”

In the winter of 2007, just a few months before KIPP was supposed to start its new school on the Cole campus, the charter network called it quits.

KIPP wouldn’t attempt a school turnaround effort across the country for another seven years.

MANCINI: “We did not have an approach beyond a phase-out period. We had to go back to our basics and stay focused on starting schools from scratch.”

It was a told-you-so moment for community members who raised concerns about KIPP.

LAWLESS: “We were obviously very pissed off that it didn’t work. As a community, we did good, solid research. We were able to identify the issues that brought KIPP down. And the state would have done well to listen to us.”

With KIPP out, Cole was effectively closed. But DPS, under then-superintendent Michael Bennet, now Colorado’s senior U.S. senator, pledged to do right by the community.

In the fall of 2008, a new district-run K-8 school, the Cole Arts & Science Academy, or CASA, opened on the Cole campus. And at the request of the community in 2010, one of Denver’s most successful charter school networks, DSST, also opened a school on the shared campus.

Cole’s history weighs heavily on the leaders of the two schools now.

Jennifer Jackson, principal of Cole Arts & Sciences Academy, said the district owes the neighborhood.

JENNIFER JACKSON: “There is a tremendous amount of pressure to do right by a community that hasn’t always served them well. Sometimes, when I think about it, it’s a lot. But it’s a job of any school leader to create a place where kids want to come and families feel safe. If this school didn’t do well before, how do we make sure it does well going forward?”

Rebecca Bloch, director of DSST Cole, which has a middle and high school on the campus, said she hopes students can spend their entire public school career there.

REBECCA BLOCH: “My dream is in a couple of years from now you have a world-class education on one city block of Denver, in an area that has historically not served students well. I think we can do that. It’s exciting to think of a kid rolling out of bed when they’re four and being with us until they’re 18.”

The campus still has its share of academic struggles. Test scores at the district-run elementary and DSST middle school still lag behind the city. DSST Cole Middle School’s results are uncommon for a network that includes some of city’s best schools.

PART V “It’s really hard to figure out what to do.”

Thirteen years after the state attempted to improve Cole, the state is about to engage in similar work. A dozen schools and five school districts face state intervention because of chronically low test scores.

This time, the state board will have more options to consider in addition to charter school takeovers. It could decide to close schools, turn over portions of schools or districts to outside management companies, or direct schools to submit their own plans take advantage of the state’s innovation law. Schools granted innovation status get waivers from district and state policies.

Yet even with a greater range of options, the work of school turnaround remains daunting. And many questions on how to apply the state’s law still remain.

HUDAK: “It’s really hard to figure out what to do. When schools are consistently low-performing, the reason they are is because they usually have really poor students and the neighborhood hasn’t changed. Every school is different, every situation is different. There has to be more choice that the school and the school board can use to fit the unique needs of that neighborhood.”

State education department officials also are asking local school districts to weigh in on their futures, something former Cole principal Nicole Veltze and former state board member turned superintendent Rico Munn recommend.

VELTZE: “We had a law that didn’t make sense. It rendered people powerless. The state has to allow the districts to have a voice in what happens. And that the decision should be based on a body of data. Turnaround takes time and it needs the right leadership. This is also a community effort. And the voices of the family, and their participation, is critical for doing this work.”

MUNN: “There has to be the ability to have a dialogue with the state and the state board has to deal with the day-to-day reality of the challenges schools face. I spent probably three nights a week meeting with Cole families for months before coming up with what was not the best decision. Even with as much information and knowledge as I had, we didn’t get it right. The state board needs to be fully aware of how much they don’t know.”

One thorny issue is what happens to successful schools in struggling school districts — especially if the state takes the most drastic action under the new accountability law and strips districts of their accreditation. The state has never removed its seal of approval from a school district before and it’s unclear what the consequences of that action could be.

GROVER: “I don’t think anyone had a grasp on the overall effect the law would have. The lesson is transparency. Teachers really need to know all the pieces and components of closing and handing off a school. You also have to think of the students who are sitting in those schools who are learning, who are doing everything right, and the parents who are involved. So what happens to those students, as well as the students who aren’t necessarily plugged in?”

There’s also the question of whether the options the state board has at its disposal can do any good if districts aren’t creating conditions for a successful turnaround.

LAWLESS: “Whoever is making a decision about a school takeover, you have to think about the principal leadership and their capacity to engage with our students in our communities. Principals also need enough time to actually put their plans in place. And they need a way of working with the teacher hiring system. They have to have the first pick of top teachers in the district who will buy in.”

There’s also the question of time. If the state board directs a school to be turned over to a charter operator, how much time will that charter school have to get up and running?

MANCINI: “We learned how you get started is really critical. You want to have a leader to get the school off to a really strong start. You need to pick someone who is an experienced educator who is up for the challenge. Another recommendation we would have is to leave at least a year between the approval and the opening of the school. Three months between approval and opening is too brief. School leaders need the time to start building relationships in the community and identifying/training the school leader. You have to choose your teachers really well. They need to be extremely skilled in reaching a diverse group of students. And you have to provide a lot of support for those teachers and a lot of training. This is extremely hard work.”

Update: This post has been updated to better reflect a quote about principals at Cole being interviewed by the Denver media, and the role it played in discouraging principal candidates.