Westminster schools may have failed to identify scores of students needing help learning English, and also neglected to effectively teach many of those students, according to a federal investigation. Those are among the findings in newly released documents behind the school district’s agreement to boost services for English learners.

The 9,400-student district signed a settlement agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice in February, which outlines changes the district must make.

Despite the district’s agreement, Westminster Public Schools officials dispute the investigation’s findings.

“We still maintain that we were not out of compliance with the law,” said James Duffy, the district’s chief operating officer. But he said in the interest of students, “instead of continuing to argue and waste resources going back and forth, we are going to meet the agreement.”

Many of the disagreements center on how Westminster places and advances students based on proficiency rather than age, which is known as competency-based learning.

The district’s model also has put it at odds with the state. Last year, the district argued that Colorado’s accountability system unfairly flagged Westminster’s district for low performance, in part because some students were tested by the state on material they hadn’t yet been exposed to.

Below is a breakdown of the major ways the government believes Westminster schools were violating the law in serving English learners, the way the district argues they weren’t, and some next steps.

- Finding: Westminster Public Schools has not identified all students that need English language services.

District officials said they had already identified problems in their process before the Department of Justice pointed them out, and were in the process of changing their system.

When a student enrolls in school, most districts require parents to fill out a home language survey that asks the language the students speaks and the language spoken in the home. The problem, in part, was that Westminster officials, years ago, were not testing students whose home language was something other than English, so long as parents had noted that their child did speak English.

“Based on experience with other states and school districts…this practice frequently results in the under-identification of ELs,” the justice department wrote.

This year, state numbers show Westminster has identified 38 percent of its 9,400 students, or 3,615, as English learners.

Officials said they have been using a new form, and said students are now tested for English proficiency when parents identify a primary language in the home that is not English. Teachers also can flag a student for testing and services.

The settlement agreement also requires the district to identify long-term English learners who have been enrolled in American schools for more than five years without making progress toward fluency.

Officials said they have identified 730 long-term English learners in the district. Parents of those students will soon receive letters asking if they are interested in sending their children to school this summer for a program to help those students make more progress.

- Finding: Westminster Public Schools is not providing adequate services for students that need English language development.

According to the Department of Justice findings, most students in the district aren’t getting help to learn the language.

“Our site visits and review of data revealed that the type of language assistance services (English learners) receive varies widely, depending on which school they attend,” the department states. And when students are getting instruction to learn English, they aren’t always getting it from a teacher who is trained and certified to do so, they found.

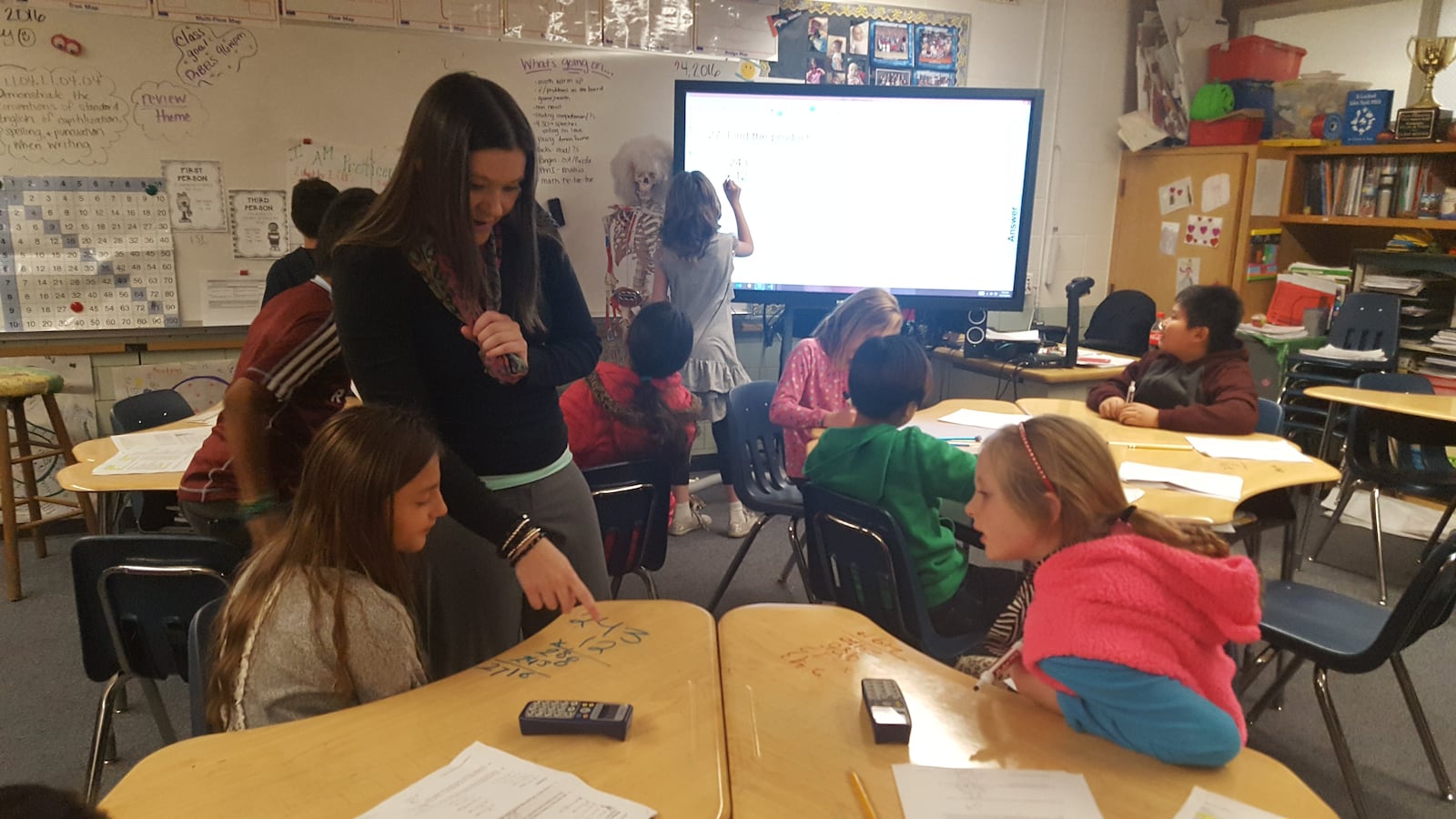

Westminster schools use what they call an “interventionist framework” that combines specialists who have Colorado’s Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Education endorsement, as well as other specialists, including special education teachers, to form a team of “interventionists” that all work with lagging students. That team works by going into classrooms throughout the day.

It’s a system that, in part, helps maximize the number of teachers working with students when the district doesn’t have enough of one kind, but it also can target which kind of help a student needs, Duffy said.

“We look at the need of our students and not the broad brush labels,” Duffy said. “They are getting services from a number of people. This is a program that has been recognized.”

But the district only tests students in English, meaning some students may not get an appropriate education.

When the district is trying to figure out what class levels to place a new student in, they test them for math and English using tests in English, so if a student can’t understand the test, they may not be able to demonstrate their ability to read or to do math and end up placed in classes below their ability.

District officials say that once in classrooms, teachers look at data closely and can determine if a student has been placed incorrectly just because of a language barrier. Teachers also have some flexibility in how they ask students to show they’ve learned a standard so they can move to another level.

“It’s just an initial placement,” Duffy said. “They are approaching this from a very traditional model. It’s not in alignment with our system.”

As part of the settlement agreement, however, the district must develop new procedures for testing and placing students, including “assessing ELL’s literacy and math levels in Spanish where appropriate and available.”

- Finding: The district does not have enough staff for its English language learners and does not provide teachers with enough training to help students in their classes.

District officials admit they cannot hire enough trained staff to work with all students, but point out that it’s not a problem unique to their district.

According to district-provided numbers from December, 83 district staff have a Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Education endorsement. The February settlement agreement asks the district to increase the number of teachers with the endorsement.

To recruit these highly-sought after teachers, Westminster officials have gone to national job fairs and have provided signing bonuses for hard-to-staff positions, including for teachers with this credential. Going abroad to recruit foreign teachers has not been something Westminster can afford, Duffy said, but the district would hire qualified foreign teachers if they applied.

Westminster also provides out-of-state teachers with a stipend for moving expenses but runs into the high cost of living in Colorado.

“It’s scaring a lot of people away,” Duffy said.

One other incentive Westminster and many other districts offer is a tuition subsidy for teachers interested in earning the endorsement.

The Department of Justice also will require Westminster to develop new and additional training for district teachers who don’t have the credential, so they can better teach language learners.

The district is going to work with the University of Colorado Denver to provide that training. Duffy said officials submitted their teacher training plan to the Department of Justice, and are awaiting approval.