Educators, parents, and social workers told of students struggling with depression, younger and younger children attempting suicide, and youths ending up in prison. A bill approved Thursday by a Colorado House committee would pay for a three-year trial to provide social and emotional help for elementary students in the hopes of addressing some of these challenges.

If approved by the full legislature and signed into law, the measure would create a three-year pilot program at 10 high-needs schools. It is estimated to cost about $5 million a year. House Bill 1017 would place social workers, counselors or psychologists in every elementary grade at the test schools starting next year.

In an impassioned presentation, bill sponsor state Rep. Dafna Michaelson Jenet, a Commerce City Democrat, said schools need more social workers “to stop our children from dying by suicide, from ending up incarcerated, from being failed by our system.”

Suicide is a leading cause of death among youth ages 10 to 24 in Colorado, and advocates of the bill said schools are often ill-equipped to deal with children suffering from trauma, bullying and behavioral challenges.

The bill was scaled back from an original version that would have cost $16 million a year. Michaelson Jenet said the nearly $5 million annual cost would be funded in part by $2.5 million from the state’s marijuana cash fund, with the rest from private foundations.

The National Association of Social Workers recommends one social worker for every 250 students, and one for every 50 students at high-needs schools.

Colorado schools don’t come close to those numbers.

About one-third of the state’s 178 school districts employed social workers during the 2016-17 school year, the most recent for which data was available from the Colorado Department of Education. Those districts represented about 89 percent of that year’s 905,000 pre-K through 12th grade students.

The nearly 590 social workers employed worked out to less than one full-time employee per 1,000 students.

Englewood’s Sheridan School District had three social workers for 1,511 students, while Yuma County had 1½ social workers for 807 students.

The two largest districts, Denver and Jefferson County, employed more than one-third of school social workers that year, with more than one social worker for every 1,000 students. Denver voters approved a 2016 tax to help pay for more social workers.

But many districts have no social workers. And most school social workers are stretched thin.

Jessie Caggiano is a social worker who serves more than 3,000 students at four high schools in Weld County.

“I’m not able to meet with students effectively on a one-on-one basis, because I’m trying to implement other services schoolwide,” she said. “I’m only at each of my schools one day a week, so I’m not able to meet their needs by any means.”

Darlene Sampson, president of the Colorado chapter of the Association of Black Social Workers, recalled working at a Denver school when a student was killed in the cafeteria.

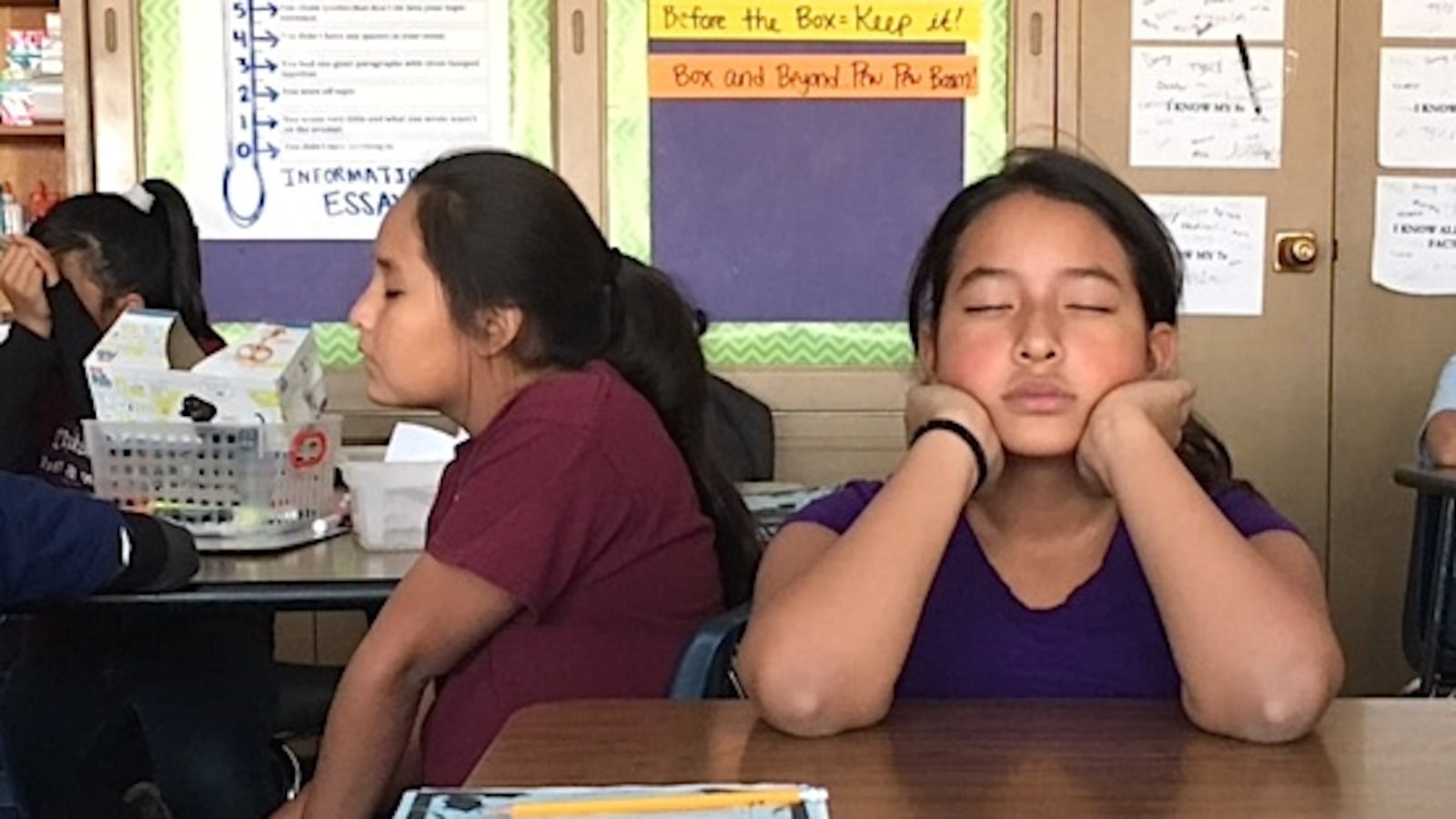

“Many kids are carrying their trauma in their backpacks into the school,” Sampson said.

And Cam Short-Camilli, representing the Colorado School Social Work Association, said students are facing increased emotional problems at most schools. The increase in youth suicide and suicide attempts is especially difficult, she said. One Denver incident last fall attracted national attention.

“Every school district, every student is impacted, that’s rural, urban, suburban schools,” Short-Camilli said. “In the past five years, I’ve been at elementary schools, and it’s been extremely shocking. Kids at those schools, there’s an immense ripple effect.”

But state Rep. James Wilson, a Salida Republican, questioned whether the pilot program would be possible to replicate because of the high number of professionals needed.

“I’m sitting here feeling like the Grinch,” Wilson said. “I cannot bring myself to put together an unrealistic pilot. Will it really work in the real world?”

State Rep. Janet Buckner, an Aurora Democrat, also expressed concerns, but voted for the bill.

“I’m concerned how we’re going to fund it,” she sad. “The suicide rate is off the chart and our kids need so much help. I don’t think we can wait. I have a lot of phone calls and emails about this bill, people who really need the help.”

HB-1017 next goes to the Appropriations Committee before being considered by the full House, then the Senate. It is one of several measures aimed at offering help for students and their families beyond academics at public schools.