The Denver teacher strike was, at its core, a fight for higher pay. But it was also a backlash against controversial school district policies, ballooning bureaucracy, and a sense that the powers-that-be weren’t listening to teachers.

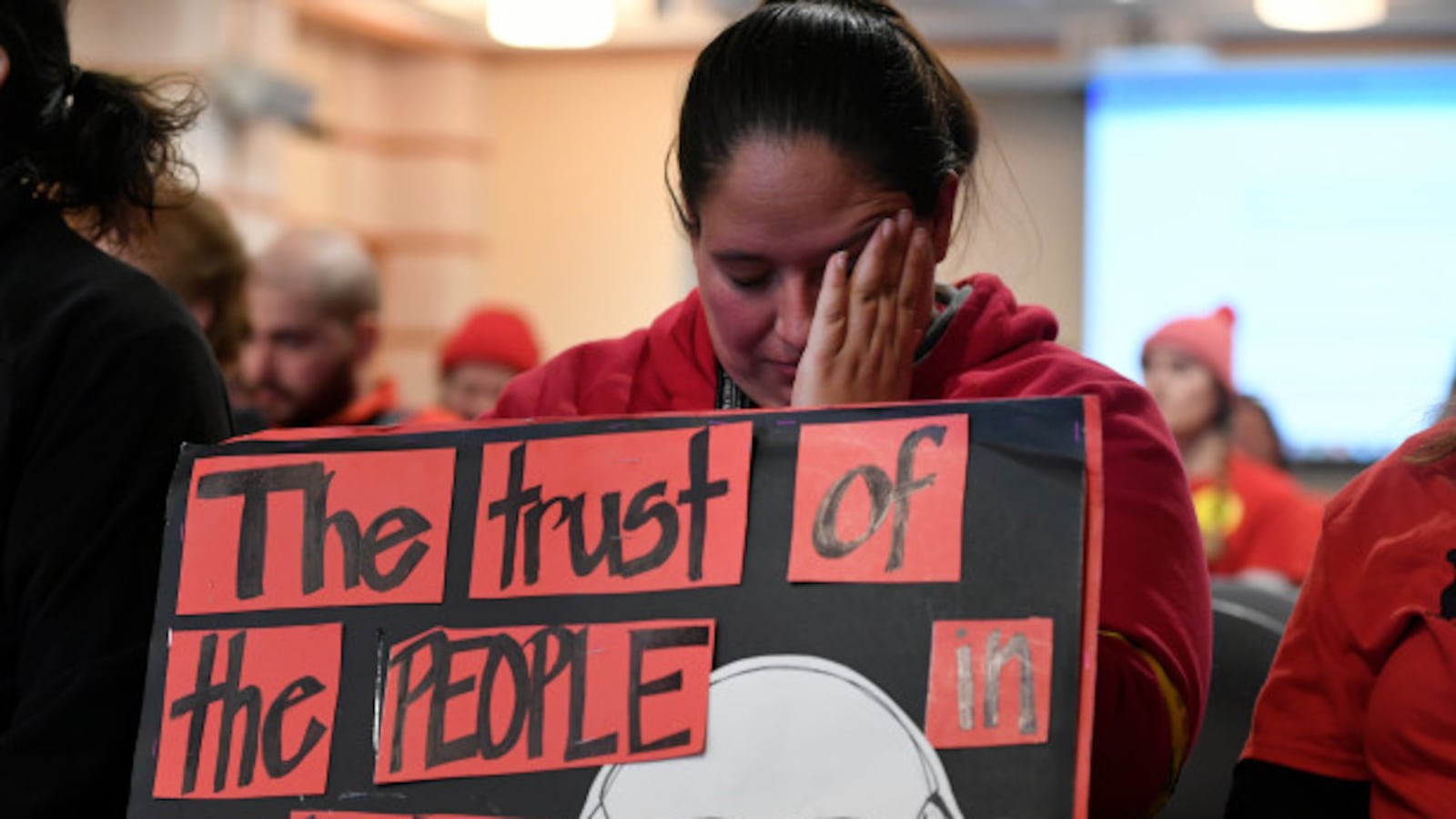

Amid all of that, a battle cry that originated with black education activists in Denver began catching on with teachers and the parents supporting them: “Flip the board.” The message was written on signs, appended in hashtags to social media screeds, and shouted at rallies.

“Flip! The! Board!” teachers chanted. “Flip! The! Board!”

The message is a reference to the Denver school board, a seven-member body that sets district policy and acts as boss to the superintendent. For the past decade and a half, a majority of them have agreed with a set of policies — such as paying teachers based on merit, closing struggling schools, and opening new charter schools — that have made Denver Public Schools a nationwide exemplar for a certain brand of education reform.

But those same reforms fueled the frustration that drove many teachers to picket. The call to “flip the board” represents a desire to elect members who think differently. Advocates and parents who have long allied themselves with the board minority — opposed to school closures and skeptical of new charters — hope to parlay the anti-establishment momentum from the strike into a victory at the ballot box in November.

There are distinct opportunities this year. Term limits bar two incumbent board members from running again, leaving the field for those seats wide open. A new progressive political player with some successes under its belt is active in Denver. A longstanding Democratic consensus around education reform has frayed in the Trump era. And the strike created a vivid public display that all is not well within Denver Public Schools.

“The consciousness of the Denver community around public education has been taken to an all-new high,” said Hasira “H-Soul” Ashemu, an activist who is part of a coalition to recruit candidates and support them. “We’re going to seek to capitalize on that.”

But the people who have supported the board majority in the past downplayed the ways in which this year is different. Education reform has always been contested ground. Jen Walmer, head of the Colorado chapter of Democrats for Education Reform, said she isn’t interested in sowing political division but is rather focused on improving education outcomes for students.

With the election nine months away, it’s not even clear who the candidates will be or what the races will look like. Just one person, Tay Anderson, has declared. “We have no idea what this field is going to be like,” Walmer said. “Maybe we’ll agree on the same candidates.”

Three of the seven board seats are up for election this year. If enough candidates who want to change the status quo win, the board minority will become the majority, “flipping” the balance of power in Colorado’s largest school district for the first time in recent history.

But what that means, exactly, is complicated.

History lesson

Fifteen years ago, Denver Public Schools was far from an exemplar. It was bleeding students; about a quarter of children who lived in the city crossed the border to attend public schools in nearby suburbs or paid for private ones. The students who remained, on average, posted reading and math test scores well below the statewide average.

District leaders took drastic action. That included tying student test scores to school ratings, and using those ratings to help determine which low-performing schools should be closed. At the same time, the district nurtured the expansion of high-performing charter schools, which are publicly funded but independently run by nonprofit organizations. A quarter of Denver’s schools are now charters, which is far more than in any other Colorado district.

Charter schools are controversial. In Denver, the teachers union has accused them of siphoning students and money from traditional schools. Opponents claim charters are “privatizing” public education. And because they are supported nationwide by philanthropies that draw their money from wealthy entrepreneurs, charters are often vilified as serving corporate interests.

A big part of what allowed Denver Public Schools to close struggling schools, open new charters, and become a school reform darling was the continued support of the school board. In every election cycle, reformers held onto the board majority. For two years, in 2016 and 2017, they even held all seven seats, lending unanimous support to the district’s strategies.

Backers of those strategies say they’ve worked. Denver’s test scores have risen to within a few points of statewide averages. The graduation rate is up, and the dropout rate is down. Enrollment has swelled, and many families with the means to do so no longer flee the district.

Critics argue the gains have come at a cost. While the district talks a lot about equity, test score gaps between students from low-income families and those from wealthier ones, and between students of color and white students, have widened over time. Denver’s embrace of school choice has in some ways exacerbated school segregation. And closing neighborhood schools that served as the heart of communities of color has had unintended effects.

Despite those concerns, Denver voters have continued to hand victories to reformers. School board elections have historically had low voter turnout. In November 2017, when four seats on the board were up for grabs, only 32 percent of registered Denver voters cast ballots in the biggest of the four races. The elections have also historically been small money affairs.

But that’s no longer true in Denver. In 2017, groups affiliated with Democrats for Education Reform spent almost $428,000 to elect candidates who supported the district’s direction. Groups funded by teachers unions spent nearly $260,000 to elect candidates who did not.

The result was split. Two candidates backed by reform groups won, as did two candidates backed by teachers unions. Those two candidates, Jennifer Bacon and Carrie Olson, both former teachers, now make up what many people think of as the board minority. (A winning reform-backed candidate, Angela Cobián, is also a former teacher.)

The meaning of the word ‘flip’

Unlike in the past, when the board minority was openly hostile to the ideas championed by the majority and the district hired a marriage counselor to try to repair the rift between the two sides, the seven members who currently serve on the board tend to disagree politely. A lot of votes are actually unanimous. That includes the most important decision the board made this year: to hire longtime district administrator Susana Cordova as superintendent.

Board Vice President Barbara O’Brien said she doesn’t think of the board as divided.

“I don’t understand what they mean by ‘flip the board’ in today’s context,” said O’Brien, who was elected in 2013 and remembers when the board was more contentious.

Now, she said, “we have quite a diverse set of experiences and perspectives on the board, and we’re still almost always making unanimous votes.” She credits that to the work all seven members do before a vote to accommodate everyone’s perspectives.

But there are sometimes subtle differences in approach between the majority and minority.

Bacon and Olson have asked different questions about decisions such as whether to give district-run schools charter-like autonomy. In a district with a reputation for ignoring community wishes, the two, along with Cobián, have pushed to do a better job listening to what students, parents, teachers want. Bacon has elevated a conversation in recent months about how the district can better serve black students. Shortly after she was elected, in what was largely a symbolic vote, Olson stood alone in refusing to sign off on the contracts of five new charters.

And two weeks ago, when the district and the teachers union worked 20 hours straight to hammer out a new pay deal, Bacon and Olson kept vigil with the teachers throughout the night — after joining them at rallies and on the picket line earlier in the week.

At the same time, the board has adopted a much more cautious approach to school closures. It was Lisa Flores, a reform-backed board member, who initiated that discussion.

Not just a ‘catchy hashtag’

One of the first people to use the phrase “flip the board” in Denver was parent activist Brandon Pryor, who has emerged in the past year as one of the strongest voices for change, often making his case with the help of leaked district documents.

“The reason we started saying ‘flip the board’ is because the current school board hasn’t done anything or taken any measures to change the equity debt that’s in the district right now,” Pryor said. By “equity debt,” he means the district has done a poor job in serving the black and Latino students who make up the majority of its 93,000 students.

“We want to get people in there that have the community’s best interest at hand and are willing to partner with the community to ensure that things change — and not just paternalistically decide what’s best for us,” Pryor said.

Pryor said he’s happy the phrase “flip the board” is catching on, but he doesn’t want the focus on students of color to get lost. “I don’t want it to be all about a catchy hashtag or a Facebook group page,” he said. “How is equity going to be included in flipping the board?”

The Facebook page he’s referring to was started by a retired Denver teacher. Several parents help administer it. Before and during the teacher strike, it was called “Fair Pay for Denver Teachers.” With nearly 4,500 members, it became one of the main online gathering places for teachers, parents, and community members supportive of the strike.

After the strike ended, the administrators changed the name to “Flip the DPS Board 2019” and updated the description. “We have a great deal of momentum,” it now says, “and we will continue to shine a light on the truth about corporate education reform. #fliptheboard.”

Parent Margaret Fogarty helps administer the page. To her, flipping the board is about electing new members who are willing to question the district’s direction.

“It’s asking questions about, ‘Is this where we want to be? Is high-stakes testing the end-all, be-all for what we want our kids to be able to accomplish after their schooling?’” she said. Other questions she said she’s thinking about include what more the district should be doing to integrate its schools, and whether it should slow the growth of charter schools.

“It’s complex,” admits Fogarty, who is a relative newcomer to this fight. “There’s a lot of degrees of what people are looking at in terms of flipping the board.”

Walmer, of DFER, said the post-strike momentum around “flipping the board” won’t fundamentally change what DFER believes in. But she said it will push the organization to do a better job highlighting what she characterized as “large support” for the policies Denver Public Schools has put in place that are making a difference for students.

Similarly, Krista Spurgin of Stand for Children, which has also supported members of the board majority in the past, said her organization won’t enter the election with “preconceived notions” about the types of candidates it will back. But she cautioned against change for change’s sake, especially if that involves getting rid of improvement strategies that are working.

“We’re currently focused on, ‘How are we going to heal as a district after the strike?’ versus ‘How can we continue to divide?’” Spurgin said.

O’Brien said she expects this year’s election to be hotly contested. But if past history is any judge, she also expects the fiery “I’ll never” rhetoric from the campaign to give way to more collaborative decision-making once new members are seated.

“Whoever gets elected, the reality of what you’re working on and the various stakeholders who have different opinions about their children’s education, it makes people work really hard to find good solutions, and the rhetoric kind of goes away,” O’Brien said.

Asked about the movement to “flip the board,” neither Bacon nor Olson disparaged their fellow board members. But they did acknowledge a growing hunger in the community for change.

“We can no longer have people (on the board) with policies and theories who are not able to articulate how it impacts people,” Bacon said. “DPS is in very real need of leadership. I’m incredibly interested and invested. We gotta move.”

Plan in progress

How the “flippers” plan to pull off a feat that has eluded the Denver Classroom Teachers Association and its allies for more than a decade is still a work in progress. Ashemu, who co-directs a group called Our Voice, Our Schools, is heading a coalition that aims to identify a single candidate to run for each of the three open seats.

One of the biggest mistakes made in 2017, he and others said, was that challengers to the status quo weren’t united. O’Brien, for example, won re-election with 40 percent of the vote because her two opponents split the other 60 percent.

This year, the field is wide open. The three seats up for election are held by board President Anne Rowe, former president Happy Haynes, and Flores, the treasurer. Rowe and Haynes have served on the board for eight years and are barred by term limits from running again. Flores did not return messages inquiring whether she plans to seek re-election.

Anderson, the only candidate to announce thus far, has kicked off a campaign for Haynes’s seat. A recent Denver Public Schools graduate who works as a restorative practices coordinator at North High School, he is firmly on the side of the flippers. He also ran in 2017, ultimately losing to Bacon, who won the union’s endorsement over him.

The coalition hasn’t yet announced which candidates it will back or how it will support them. But Ashemu said it’s clear that their strategy will have to go beyond money. While deep-pocketed donors such Colorado billionaire Phil Anschutz and national organizations such as Democrats for Education Reform and Stand for Children have supported pro-reform candidates, those on the other side have relied on teachers unions to fill their more modest war chests.

“We understand that we have to do with people what the other side plans to do with money,” Ashemu said. “We really are going to have to be better wordsmiths, and use social media, and use things at our disposal in order to have an impact on the consciousness of voters and populations that before now have been disengaged.”

One of those populations will likely be the Denver teachers, parents, and community members for whom the strike was something of a crash course in school district politics. Henry Roman, president of the Denver Classroom Teachers Association, said he expects this year’s election to be marked by heightened awareness and activism among educators, some of whom don’t even live in Denver but who are already pledging their help to “flip the board.”

“Because of the strike, people are paying close attention,” Roman said, “not just to their paychecks, but they are also looking at the link between what’s happening in the classroom and the role the Denver Public Schools board of education plays in that context.”

The flippers will have help from the Working Families Party, a national political organization that is relatively new to Colorado. The group, which gets funding from labor unions as well as individual members, played a minor role in the 2017 Denver school board election and a bigger one in last year’s Colorado House and Senate races, where four of the five candidates it supported won competitive Democratic primaries, including against better-funded opponents.

It makes sense, Deputy Director Wendy Howell said, that campaigning for change on the school board would be the next step for those who were “fired up” by the strike. Denver’s complicated teacher pay system, she said, “is just one piece of a much larger thing.”

“It’s the much larger thing that needs tackling,” Howell said. “And that is fundamentally electing a school board that reflects community voices rather than outside interests.”

Fernando Sanchez, a math teacher at West Leadership Academy, a high school in west Denver, agreed that the strike reflected larger problems in the district. Standing at a busy intersection on the third day of the teacher walkout, he gestured toward a crowd of red-clad educators who were there with him, waving signs and chanting for change.

“The board is the leader, and if they allow this to happen, it’s not functioning and something needs to change,” he said. “If they won’t change it, we need to change it ourselves.”