The reading courses at Colorado’s largest educator preparation program don’t match up with research on literacy instruction, and many of the professors have philosophies that contradict state standards, according to a scathing new critique by state evaluators.

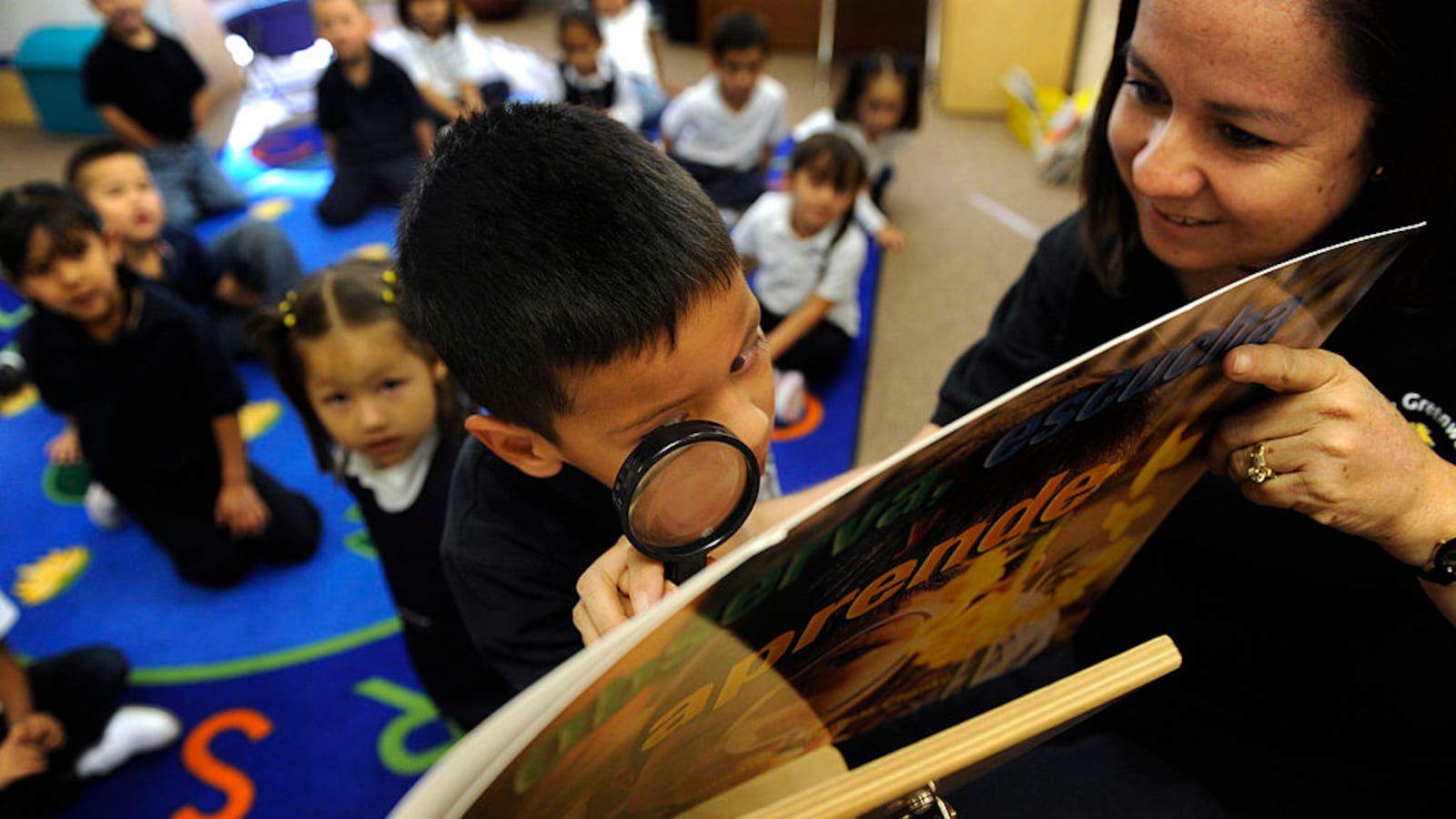

The Greeley-based University of Northern Colorado, which enrolls about 2,800 teachers-in-training, is the first institution to face new scrutiny from state education officials over how it prepares students to teach reading. The literacy appraisal was part of the prep program’s reauthorization review and comes amid widespread concern about reading instruction and mounting pressure from state lawmakers to find solutions.

Even as more than half of Colorado children read below grade level and millions of dollars spent on interventions have yielded disappointing results, many teachers report that their own training programs did not equip them to help children learn to read.

In a 15-page reauthorization report, state officials detail a number of specific problems with the university’s core literacy courses, including that they emphasize prospective teachers’ beliefs about reading rather than forcing them to draw science-based conclusions.

“A lower bar for education prep [candidates] versus the students they’ll be teaching is concerning,” the report states.

Obtained by Chalkbeat through an open records request, the report grants the usual five-year reauthorization term, but requires the prep program to meet five conditions by February 2020. They include aligning course syllabi to state standards and increasing science-based reading instruction. (Read the full report at the end of this story.)

Officials at the University of Northern Colorado, the first institution to undergo reauthorization since the state doubled down on reviewing reading instruction in 2018, said many of the report’s critiques are unfair — stemming from poor communication by state officials about what they expected and hastily planned meetings during a campus visit. They also said officials portrayed the new focus on reading instruction during the reauthorization process as a low-stakes pilot program.

In coming months and years, state officials plan to evaluate other teacher preparation programs using the same approach that was used at the University of Northern Colorado. Those programs could also have to accept new conditions to keep their state authorization.

“I think this is one important lever,” said Amy Pitlik, government affairs director at Stand For Children Colorado, an education advocacy group.

She said the state’s rigorous review of the University of Northern Colorado’s prep program will put other universities on notice that the Education Department is taking its role in reauthorization seriously when it comes to literacy instruction.

Metro State University in Denver and Colorado State University in Fort Collins are among the institutions that will undergo reauthorization of their teacher preparation programs next.

Despite major misgivings about how state officials came to their conclusions, Corey Pierce, associate dean of the University of Northern Colorado’s College of Education and Behavioral Sciences, said he believes both state and university officials have the same goal: producing good teachers. He also said some elements of the critique are justified.

“When we read through [the report] we said, You know what? This is a good time to go back and look at the sequence of courses and how we do teach reading,” he said. “Every once in a while it’s good to reset and get everybody back on the same page.”

Frustration mounts

The state’s new effort to scrutinize how Colorado’s future reading teachers are trained comes at a time when educators, lawmakers, and school district leaders in Colorado and the nation are grappling with a seemingly intractable problem: thousands upon thousands of students who can’t read well.

A 2012 state law called the READ Act aimed squarely at this problem, requiring districts to provide extra help to struggling readers. Unlike other education reform legislation around that time, it came with extra funding for schools. But Education Department officials admit the state’s made only slight progress in ratcheting up proficiency rates since the READ Act was passed. Now, lawmakers are questioning whether school districts are making good use of the money and whether the state needs to get more involved.

Last year, about 15 percent of all kindergarten through third-grade students had major reading problems that qualified their school districts for extra money under the READ Act. But more students than that are reading below grade level. Last year, 60 percent of Colorado third-graders weren’t reading proficiently, according to state test results.

National tests not only show similar results for Colorado students, but also highlight the state’s stagnant reading scores. All five times the national reading test was given from 2009 to 2017, only about 40 percent of Colorado fourth-graders scored proficient or above.

At a legislative committee late last year, state Sen. Bob Rankin, a Carbondale Republican, asked Education Department officials, “Do our teachers know that body of science? Are they being taught in school how to teach reading?”

“That is truly an issue,” said Melissa Colsman, associate commissioner of student learning at the Colorado Department of Education. “That is actually something we hear quite a bit from principals, literacy coaches, superintendents — that is, the need for teachers to understand the science of reading.”

She went on to say that while Colorado’s teacher licensure standards do require the state’s teacher prep programs to cover the science of reading, half of the state’s teachers are trained elsewhere, their backgrounds an “unknown quantity.”

But as the state’s critique of the University of Northern Colorado’s prep program demonstrates, standards alone don’t guarantee that teachers are learning what they should.

Unprepared

It’s easy to find teachers who don’t think their preparation programs, whether in Colorado or elsewhere, adequately prepared them to teach reading.

Years ago as a classroom teacher, Deborah Blake would go through a whole list of strategies when one of her young students would stumble in reading a word. First she’d ask them what would make sense in that spot. Then she’d suggest they look at the picture and think about the story. If that didn’t work, she told them to get their mouth ready for the beginning sound and to look for chunks they might know. The last thing on her list was to ask the student to try sounding out the word.

“I was teaching my students to guess instead of to read,” she said.

Blake is now a special education teacher in the Adams 12 school district north of Denver. With a master’s degree and a raft of specialized trainings under her belt, she’s confident she can help all kinds of kids learn to read.

But she readily admits her original teacher preparation program at the University of South Carolina Aiken didn’t do the job. The one required reading course there focused on reading stories aloud to children and then doing a related activity with them, she said.

Blake was among the nearly 70 educators who responded to a recent Chalkbeat survey about reading instruction. Most felt their preparation programs — usually undergraduate programs but occasionally graduate programs — didn’t address the science behind reading instruction. Many said they eventually learned more, sometimes decades after entering the profession, through school district trainings, master’s degree programs, or their own research.

Jon Cefkin, a first-grade teacher in the Jeffco district west of Denver, said he got his teaching certificate as part of a design-your-own master’s program at Denver’s Regis University in the 1990s. He took classes on children’s literature, but didn’t learn about the mechanics of reading instruction.

“Reading wasn’t really strong in my repertoire,” he said.

That changed later after intensive on-the-job training provided by his school district.

Today, Cefkin often has student teachers from the University of Northern Colorado or Metro State, and when it comes to reading instruction, he said, “I would just say they have the real basics … I guess teachers kind of have to learn on the job.”

More teeth

Before this year, Colorado Education Department officials didn’t focus heavily on reading instruction when deciding whether to reauthorize teacher prep programs. Although the programs technically had to comply with state literacy standards required of teacher candidates, state officials didn’t delve as deeply or require detailed proof of compliance the way they do now.

Things began to change in 2016. That’s when the State Board of Education approved more explicit literacy standards and made it easier to hold prep programs accountable for meeting them. But it wasn’t until the University of Northern Colorado went through reauthorization last year that the process got some teeth.

Those teeth came in the form of two literacy experts from the Education Department who participated in the reauthorization process. They reviewed literacy course materials, visited classes on campus, and talked with faculty and students about reading instruction.

And based on the report’s long list of shortcomings — from out-of-date textbooks to inferior methods for assessing a child’s word-decoding ability — they were unhappy with much of what they saw.

During the campus visit, state officials interviewed 30 students in the prep program and none had heard of the READ Act or could name a reading researcher or journal.

The report mentioned one bright spot: a special education professor’s courses, which were described as completely aligned with all state standards and current reading research.

On Feb. 13, the State Board of Education approved the prep program’s reauthorization contingent on the five conditions the report outlined for improving literacy instruction.

Pierce said the report doesn’t accurately represent how the university approaches literacy instruction.

For example, while the report cites inadequate coverage of reading assessments in the four main literacy courses, he said it doesn’t mention that additional material is covered in a separate assessment course.

“There was no metric, no quantitative way that they measured anything that we do,” Pierce said. “The process was terribly flawed.”

He said the college declined to rebut what it views as inaccuracies in the report — as the state allows within 30 days — in part because the prep program did win the full five-year reauthorization term.

Despite his frustrations with the review, Pierce was circumspect about the outcome.

“We need outside eyes and ears to come and look under the hood,” he said. “While we wish they used a more sophisticated, true evaluative process, there are things we want to get more efficient at and get better at.”