Before I was a teacher, I was a police officer.

In that job, we thought a lot about Cooper’s four zones of awareness. Red means you’re on full alert. Orange is your state of mind when there is a possible threat. Yellow means you’re relaxed but alert. You’re in the white zone when you are relaxed and not especially aware of anything around you.

Last week’s threats to Denver schools made me worry that my students now live in a constant state of yellow-orange, with an untold impact on their mental health.

I feel like I saw this period begin 20 years ago. When shots rang out at Columbine High School, I was in my first teaching job in an urban Colorado elementary school. I lived only a mile away from Columbine, so after I got home, I walked to the scene to see if I could assist. Someone asked if I could distribute food to first responders and families waiting to hear if their child made it out alive.

I watched the hours tick by, and I watched as each family left a nearby elementary school cafeteria without a child in hand.

In the two decades since, I have been through countless trainings and drills and a few real lockdowns. All of my current students were born after Columbine. After the Sandy Hook shooting, my daughter told me she had found a place to hide in every room in her school.

When news of this armed woman began spreading last week, my phone blew up with texts from students and my own daughter. “Hey, sorry to bother you but I am worried about this woman, what are your thoughts?” “Do you think it is safe to come to school tomorrow?” “Mama, I am terrified to go to school tomorrow.”

The district ended up canceling school. But the next day, I had to walk into my classroom yet again and have tough conversations with teens who don’t feel like they can be in the calm “yellow” or “white” zone at school.

Teacher prep classes don’t teach you how to talk about gun violence this country. And while students in high school put on a brave face, you can see the fear and worry in their eyes.

Thankfully, my colleagues know how to help each other, and our students, reduce those feelings of being under threat. My principal called a meeting before school and reassured us that she would see to it that we were safe and supported, and if we needed a break to let her know. Then, other teachers and I walked into our classrooms and got back to work.

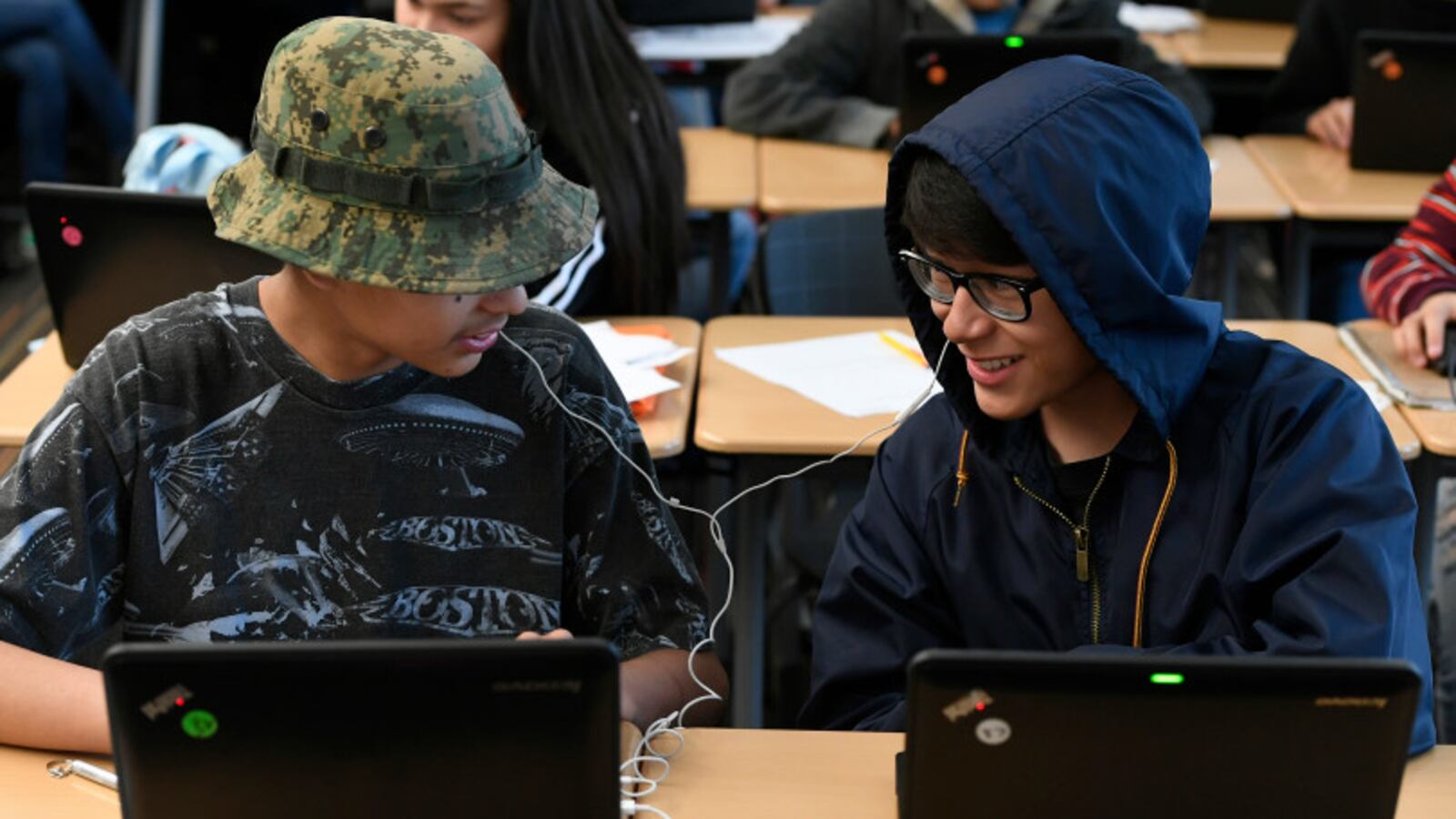

We allowed students to talk about their concerns, and did what we could to make them feel safe. We reminded them that even with the bad in the world, there is still more good. And then they went back to being teens. Some got back to work, some avoided work, a few ditched class. A few may have looked at prom dresses instead of research sites. In a world that is chaotic, normal was therapeutic.

Stacey Hervey is a criminal justice teacher in Denver Public Schools and an adjunct faculty member at the Community College of Denver and Metropolitan State University.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.