It soon could be harder for Colorado schools to earn the state’s top ratings.

Currently, the large majority of Colorado schools earn the state’s highest rating, even as most of their students are not meeting grade-level expectations in reading, writing, and math, according to state assessments.

This disconnect prompted members of the Colorado State Board of Education last fall to push for changes to the rating system so that it more closely follows test results. A series of proposals on the table could bump as many as 256 schools from the top rating to the second-highest and put a half dozen additional schools onto a watchlist for low-performing schools.

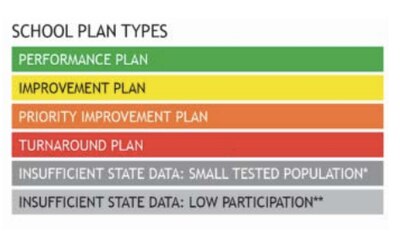

The state rating system or school performance framework has four tiers: performance (green), improvement (yellow), priority improvement (orange), and turnaround (red). Schools that receive one of the lowest two ratings for several years in a row get extra state assistance to improve, but if those efforts aren’t successful within five years, they could be closed down, converted to charter schools, or face other intervention.

“What we were looking for is some alignment,” said Angelika Schroeder, chair of the State Board of Education. “When you have 73% of schools that are at performance and the (state test) results are what they are, there’s a big disconnect.”

Some education advocates say a change is badly needed. Parents can’t make informed decisions when schools with good ratings have low achievement, they say.

But many Colorado school district leaders are watching the debate with concern. They accuse the state of moving the goalposts for “political” reasons that don’t have a connection to the quality of education.

The debate over the school performance framework ties into local and national conversations about how to calculate school quality. A collection of rural Colorado districts have been testing their own accountability systems that are less reliant on test scores, and the Denver district, the state’s largest, is about to embark on a process to revamp its rating system.

Achievement on state assessments closely correlates with race and income, and the highest scoring schools and districts serve mostly white students from more affluent families.

The state also calculates a growth score that looks at how much academic progress students have made compared with other students who got similar test scores last year.

Many testing experts consider this growth score to better reflect the work that teachers do. At the same time, many high-poverty schools with impressive growth scores still have many students who can’t read or do math at grade-level, leaving parents and education activists fearful for their long-term prospects.

“Outcomes matter to families,” Nicholas Martinez, co-founder of the advocacy group Transform Education Now, said bluntly at a recent state board meeting.

Right now, 60% of Colorado middle and elementary school ratings are based on growth, while 40% are based on achievement. At the high school level, 40% is based on growth, 30% on achievement, and 30% on measures of postsecondary readiness like graduation rates and college enrollment.

Related: Most Colorado students not proficient in reading and math — but there’s some good news

Colorado isn’t doing away with growth measures, but all the proposals would add a new metric that measures how long it would take a student growing at a particular rate to move up one level. State education officials want to see growth rates that would allow a student who partially meets grade-level expectations in third grade to be at least approaching expectations two years later, in fifth grade, and for the fifth-grader who is approaching expectations to have met them by seventh grade.

This catch-up measurement, a version of what’s called “growth to standard,” would count for 10% of elementary and middle school ratings, with the previous growth score counting for 55% and achievement for 35%. The changes to high school ratings are still a year or more away.

The various proposals also raise the bar to be considered a top-rated school, and some would add a “distinction” category for the highest performers. If the State Board makes a decision by November, its changes would affect the ratings that come out in August 2021. The ratings that come out next week, based on 2019 test scores, will not be affected.

Most Colorado schools would be unaffected by these shifts. But more than 200 would likely lose their top status, seven would move from the second tier to the third, and another six would move from the third tier to the bottom. A handful of low-performing schools would move up a level — and between 120 and 185 schools could qualify for “distinction,” if that model is adopted.

Schools that move into the lowest two ratings are subject to intervention by the State Board of Education. The State Board last year ordered the Adams 14 district to hire an external manager after eight years of low performance.

“I’m concerned about putting schools and districts on the clock by ratcheting up the expectations,” said Jeffco Superintendent Jason Glass, referring to the “accountability clock” that counts down the years to state intervention. “Even if it doesn’t lead to state takeover or being handed over to an outside entity, it uses public naming and shaming. … Do we really think these shifts will shame and compel the schools to perform at a higher level? I would look back at the last 20 years and call into question this whole theory of change.”

Oliver Grenham, chief education officer of Westminster Public Schools, said the accountability system measures just one thing: outcomes on tests.

“And that is important, but that is not all that schools do,” he said.

Westminster improved enough last year to avoid state intervention, but district officials have long maintained the current system doesn’t properly measure student progress under its competency-based learning system. Changes to the rating system could throw some schools that recently improved back “on the clock,” though state education officials haven’t determined which ones.

Board member Rebecca McClellan said she favors making changes but wants to avoid a “violent jolt to the system,” beyond the state’s ability to support school improvement efforts.

“How will this relate to the budget we have?” she asked at a state board meeting. “We don’t want to throw more schools into categories requiring help than we have resources to offer.”

At a recent state board meeting, a tense exchange between Schroeder, the chair, and member Val Flores, underscored the connection between the ratings debate and broader concerns about the role of testing in education.

“I don’t think the districts want us to keep changing things,” Flores said, “and if we do change things, what they’ll probably end up doing is teaching more to the test than actually getting to the purpose of teaching content and teaching skills and …

“Teaching kids to read and write,” Schroeder said, cutting in. “Isn’t that what we want?”

“Hopefully they’ll add other things like social studies and science and really fun things that make kids want to come to school,” Flores continued.

The Education Trust, which supports test-based accountability, has advocated for evaluations that lean more heavily on growth-to-standard.

“Parents and other stakeholders want to know if their student is on track to meet grade-level standards or to graduate college- and career-ready,” said Terra Wallin, associate director of accountability and special projects for Ed Trust. “They don’t just want to know if their student is growing relative to other students.”

Others see growth-to-standard as replicating many of the problems with achievement, in that schools serving better-off students will always do better.

“If you’re a school serving low-performing kids, you have to get more growth out of them than schools serving high-performing kids,” said Cory Koedel, a University of Missouri economist who has studied accountability systems. That’s a hard task, he added, and if the schools with the highest growth rates for students in poverty still don’t have students who meet expectations, it suggests they need more resources.

Wallin said disparities in scores might speak to real differences in how students are being educated, and we shouldn’t build ratings systems that obscure those inequities.

But Koedel said that if good ratings are out of reach for high-poverty schools, it’s deeply discouraging to the educators who work there — and a potential loss to the rest of the state.

“There is a lot of positive innovation happening in those schools that we could learn from, but if we label them as failing, we never learn from them,” he said. “To pretend that all schools serving needy kids aren’t doing a good job is kind of silly.”

Correction: This story has been changed to reflect that if the State Board adopts a new policy by November, it will affect ratings issued in 2021, not 2020.